When the collection of my essays Notes from an Unrepentant Apocalyptist (2020) landed on my doorstep, I was struck that there was a Foreword, a Preface, an Introduction by the editors and an Afterword, each of which offers a very different interpretation of the direction of my work over the years. Hence, I am indebted in this new collection to Derek Ford, Rebecca Alexander, John Baldacchino and Mike Cole for their generous assessments of my work, and to editors Marc Pruyn, Curry Malott and Luis Huerta-Charles. In each of their accounts, I found innovative ways of re-understanding the project that has been guiding my writing over this past decade. The narratives that they weave about my writings provoked me to reimagine what has been driving me all these years – and to what ends.

John Baldacchino’s reflections on my book Pedagogy of Insurrection are a case in point. While readers of my work have often seen an affinity in content and temperament with the Beats, John Baldacchino lodges the themes and passions that drive my work firmly in the Late Renaissance, in the good company of Caravaggio and Tintoretto. Only an art critic could come up with such a comparison. But his comparison did provide me with some insight as to why I have always been drawn from an early age to those very artists (though not as to why I have never referenced them in my work). When I first read Baldacchino’s essay, I wanted it to serve as the Afterword of Notes because it lays bare some of the problems he finds with my arguments, with what appear to be contradictory statements and aporias – problems that I suspect have given rise to some puzzlement among other philosophers as well. One of the challenges of transdisciplinary work is that you can often find yourself sliding down the razor’s edge of intuitive decisions, and landing on both sides of the blade, so-to-speak, and haemorrhaging too profusely to summon the requisite Aufhebung. Baldachino can’t fathom why I reject Laclau’s work on hegemony. When I read this, an image surfaced from the pottage of my memory of me dancing with Laclau and Chantal Mouffe at a party at a friend’s house in Oxford, Ohio back in the 1980s, and being overcome by a life-threatening asthma attack (the culprit turned out to be a cat hiding behind a chair next to the pulsing sound system whose feline threat my asthma radar had not detected). I was rushed to the hospital and pumped full of adrenalin. Sometimes our theories can feel too sensate: they become populated by strange accents, cigar smoke and French perfume, enfleshed with wounded memories of cats and asphyxia such that we are prevented from engaging with what Paulo Freire called an ‘untested feasibility.’ Who knows whether a cat prevented me from a more productive encounter with Laclau and Mouffe’s work. But it seems a feeble excuse for my failure to sufficiently engage with their theory. So I shall stop here and simply credit Baldacchino for his perceptiveness.

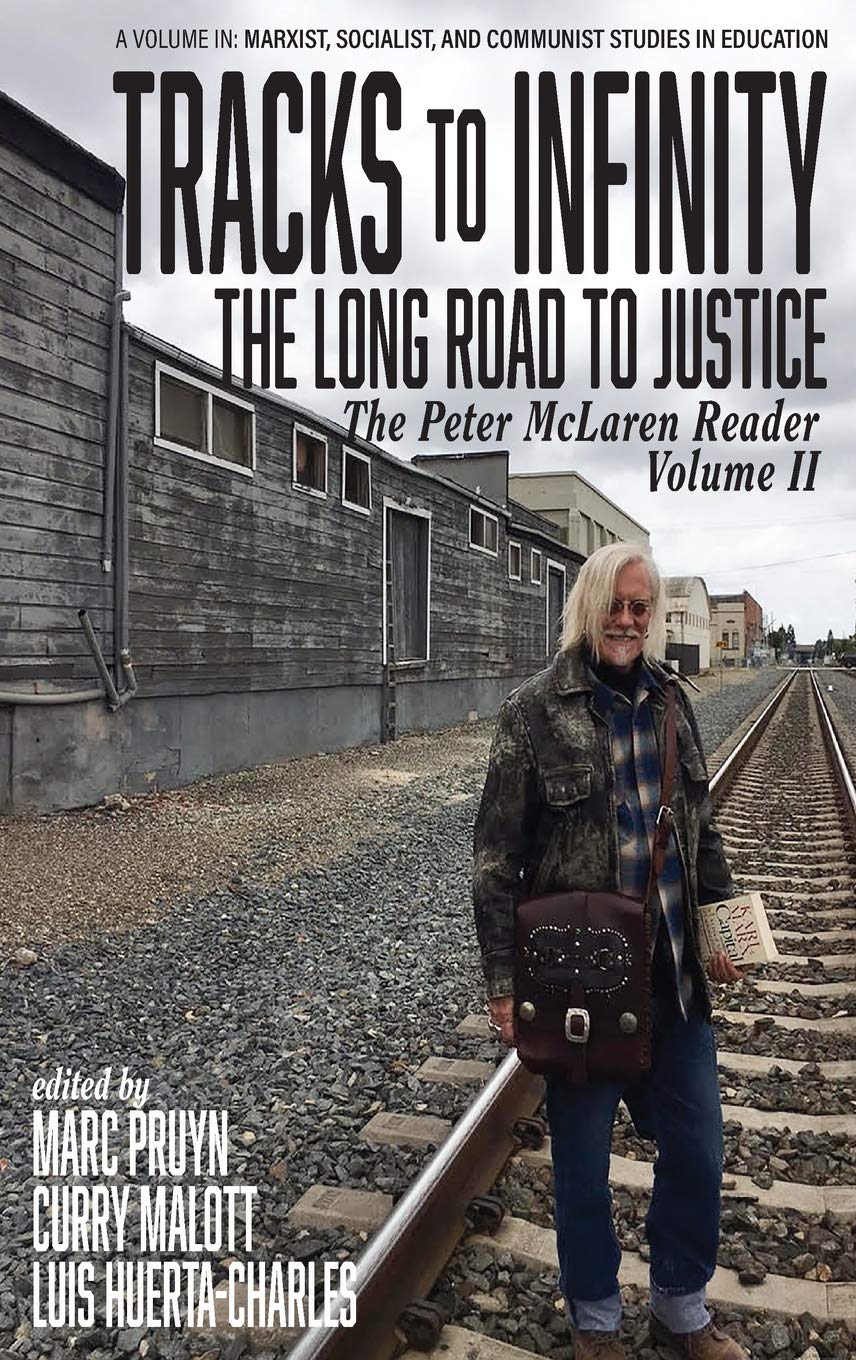

The essays that the editors and I have chosen for Tracks to Infinity reveal an abiding historical materialist engagement with a number of themes familiar from my work: the scourge of poverty and how it affects all of our research on educational reform; the savage cruelty of capitalism; the importance of a socialist alternative to capitalism and how to avoid having revolutions turn into their opposite. Cartesianism has no purchase on the reciprocal generativity of capitalism and racism, for instance. The dialectical approach to understanding the self and the social does – and has driven much of my work over the years. I have included interviews and dialogues with international colleagues that bring revolutionary critical pedagogy into dialogue with liberation theology. While I have discovered to my surprise that atheists often make the best Christians, through this dialogue, I have learned that there is a spiritual dimension to revolutionary struggle that cannot be denied and that I connect with my ancestral bones. In it, I discover the gristle and sinews of solidarity with those who struggle against the social sins of inequality, systemic racism, genocide, epistemicide and ecocide that produce so much of the world’s needless pain and suffering, and point the way to omnicide. The history of liberation theology must be disinterred from the records of the Vatican, US military and Latin American death squads who attempted to shut it down. Writing can enable you to cross new thresholds, but can also hold you captive. I have tried to ride the successive waves of concern for victims and victimisation of those who advocate for them.

The chapter ‘Critical Rage Pedagogy’ was an experiment in writing. Some readers may like it; some may be turned off. It was imagined as a play. I put myself in the character of an apocalyptist denouncing the injustices of this world. It certainly felt cathartic as I was writing it. But why it felt cathartic is the question. How is it that so many of the social sins of empire have been hidden away for so many years? And what happens when they are suddenly brought to light? Do they foreshadow even more heinous existential horrors? While many of the essays took place before Trump came to office, they might help to address the dangerously potent demagogic madness that spews forth from Trump’s maleficent maw. Fox News has become the broadcasting equivalent of the free plastic radios handed out by the Nazi Party to the German public, with their only station the one that gave them unmediated access to Hitler’s pathological ravings. Before Trump, there was Rush Limbaugh, Tucker Carlson and Laura Ingraham, but none of these functionaries of hatred has assumed the bully pulpit to which the Presidency has access, nor have their missives the dangerous potency of Trump’s tweets. Steven Rosenfeld summarizes the claims made by Burt Neuborne in his new book When at Times the Mob is Swayed: A Citizens Guide to Defending Our Republic:

‘Donald Trump’s tweets, often delivered between midnight and dawn, are the twenty-first century’s technological embodiment of Hitler’s free plastic radios,’ Neuborne says. ‘Trump’s Twitter account, like Hitler’s radios, enables a charismatic leader to establish and maintain a personal, unfiltered line of communication with an adoring political base of about 30–40 per cent of the population, many (but not all) of whom are only too willing, even anxious, to swallow Trump’s witches’ brew of falsehoods, half-truths, personal invective, threats, xenophobia, national security scares, religious bigotry, white racism, exploitation of economic insecurity, and a never ending-search for scapegoats.’ As Neuborne notes, ‘Hitler used his single-frequency radios to wax hysterical to his adoring base about his pathological racial and religious fantasies glorifying Aryans and demonizing Jews, blaming Jews (among other racial and religious scapegoats) for German society’s ills.’ That is comparable to ‘Trump’s tweets and public statements, whether dealing with black-led demonstrations against police violence, white-led racist mob violence, threats posed by undocumented aliens, immigration policy generally, protests by black and white professional athletes, college admission policies, hate speech, even response to hurricane damage in Puerto Rico,’ he says. Again and again, Trump uses ‘racially tinged messages calculated to divide whites from people of colour.’ (Rosenfeld, 2020)

If Tracks to Infinity offers an apocalyptic counterweight to Trump’s dangerous ravings, then I would be more than gratified. But the struggle will not be over when Trump leaves the White House. We must contest and transform the conditions of possibility that nurtured Trump because there are others even more gifted in creating chaos and dispensing death waiting hungrily in the shadows.