2020 American Educational Studies Association (AESA) Critics Choice Book Award

As a philosopher of education, I often find myself asking what the concept is behind sayings, mottos, and values. When George W. Bush claimed after 9/11 that terrorist groups hated United States ‘freedom,’ while Iraqis sorely needed it, I wondered what exactly ‘freedom’ meant, to Bush and others, whether everyone had the same definition of freedom, and whether one group’s freedoms might impinge upon another’s (spoiler: they can and do).

The patriotism of United States citizens is known around the world. While Americans often pit themselves against the Chinese, both countries are known for strongly sanctioning expressions of national loyalty, for example by expecting that young children pledge allegiance to national flags, and that political leaders and even athletes engage in similar nationalistic ceremonies with appropriate solemnness. While the United States protects critical speech, with some defining patriotism as a duty to challenge unjust authority, those who do not cloak themselves in and hug the flag, metaphorically if not literally, risk accusations of being ‘unAmerican’, a death sentence to a career in public office.

It is in this context that I began to wonder what patriotism really means—and whether it is a good thing. In so wondering, I quickly learned that these are timeless questions. They tie back to historical debates, about how to best affiliate with family and loved ones, versus society at large. In Ancient Greece, the Stoics debated how much partiality and care one should have toward family and friends, in contrast to a focus on cultivating higher virtue. On the other hand, how to be a cosmopolitan, a person of the world rather than a follower of a select group, has been explored continually as an idealistic possibility. Similar issues have been explored by philosophers across Asia, Africa, and elsewhere around the world: Are we firstly members of a select tribe or group? Or is common humanity the more appropriate target for our sense of love, affiliation, and duty?

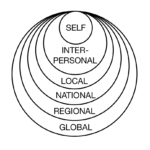

My 2019 book Questioning Allegiance: Resituating Civic Education explores these timeless debates. Starting from my deep sense of confusion about what it means to be a patriot—does it mean to be loyal, or to be critical?—it explores what it means to affiliate with, care for, and be loyal and committed toward others, across the ‘concentric circles’ of human living together.

These ‘concentric circles,’ elaborated by the Stoics, mirror the way we think about ‘living together,’ in social life and education. The circles can be described as: the family, the local community, the country and/or region, and the world.

These ‘concentric circles,’ elaborated by the Stoics, mirror the way we think about ‘living together,’ in social life and education. The circles can be described as: the family, the local community, the country and/or region, and the world.

My book ‘resituates’ civic education, because I contend that learning to live together is about learning to live in these circles. Most people do not examine citizenship education or civic education at a global level, because the subject in schools is different across societies. A comparative education researcher might say it is comparing apples and oranges. Some countries do not have citizenship education as a subject, such as the United States and Hong Kong (my two homes). So how can you compare?

Instead, I define civic education as learning to live together in broad terms, and I discover it across societies as education related to living in concentric circles. By making this turn, I show that most people learn to live together outside of any single school subject—far beyond a single subject for citizenship or civics.

My stance here reflects my view that curriculum is not just something planned by policy makers, but rather is lived and experienced. The United States does not have citizenship education—yet it has patriotic citizens. So something is happening here beyond planned curriculum. Education for patriotism is taking place in extracurricular activities (like pledging allegiance), outside the school (through media and cultural sharing), and in other elements of formal and informal education.

In a comparative study I participated in (that I discuss in the book), we asked young people in England and Hong Kong if they learned citizenship education in school. You might be tempted to predict the outcome based on facts about the curricula in these societies. In England, there is a class for citizenship education, and in Hong Kong there is not. But this is not what the students experienced. According to our participants, they did not learn citizenship education in England, while they did learn it, in their own views, in Hong Kong. These findings make it clear that we need to think more broadly about what learning to live together entails and how it works in schools.

I resituate civic education in the text by focusing on what schools teach around the world about affiliation with others, beyond any school plans or timetables for civic learning. Thus, I examine what schools teach about living within: a civilisation, nation-state, local community, family, global society, and in relation to the nature of the self. This reorientation leads to novel insights. Most people learn in schools about civilisational and national identity in history, for example. Often this education can enable a sense of ethno-nationalism. Even in countries which teach against racism and ethnocentrism, curricula which echo ‘east versus west’ and ‘Christianity versus Islam’ trace nation-states to civilisations, enabling young people to identify as westerners and easterners in problematic, harmful ways.

My reorientation toward civic education highlights how much of learning to live together is done incidentally, without a plan. In this case, messages can be contradictory about nationalism and patriotism, and about the nature of being a good citizen of one’s country or globally, ultimately yielding little of value for young people trying to navigate being good and productive in increasingly complex local and global contexts.

Resituating civic education, I find that a great deal is learned in schools (and beyond them, such as through media), but what is learned is incidental, chaotic, inconsistent, and often problematic. In this context, skills to question what is learned and what it means for how one relates to others, how one votes in elections and so on, are sorely needed, so that students learn to be independent thinkers, rather than resort in the midst of chaos into provincial and tribalist views—as we are now seeing around the world today.

The goal of education for learning to live together is to expose students to a world beyond their neighbourhood and family, to enable to them to realise how their actions impact the broader world. Yet education around the world is totally removed from this goal, as intentional civic education often contradicts messages learned elsewhere in the school building, and in media and elsewhere in society. To play a positive role, education should teach young people to question their allegiances—what they are loyal to and a part of—not to become totally cynical or skeptical, but to meaningfully actualise civic values and principles worth cultivating, in a confusing and complicated world.