The list of causalities for wars in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is horrendous with an estimated 187 million people dying in the period 1900 to the present day, with approximately 75 million in the two world wars combined.1 Hobsbawn (2002) called the twentieth century ‘the most murderous in recorded history’ suggesting ‘Chronologically, it falls into three periods: the era of world war centred on Germany (1914 to 1945), the era of confrontation between the two superpowers (1945 to 1989), and the era since the end of the classic international power system.’ Interstate wars disappeared in the Western hemisphere and in Europe but remained endemic in the Middle East and South Asia, and major wars occurred in East and South-East Asia. In the twenty-first century ‘armed operations are no longer essentially in the hands of governments or their authorised agents’ and while the number of international wars has declined, internal wars have increased, at least until the 1990s during which time the distinction between combatants and non-combatants has diminished. In short, civilians have become the main victims of war with massive displacements of peoples and the growth of refugees. The lines between inter-state and within state wars, and war and peace have become hazy and the Hague Conventions are no longer applied. While there are about two hundred states, no state or empire has ever been large, rich or powerful enough to maintain hegemony over the political world, let alone to establish political and military supremacy over the globe. The world is too big, complicated and plural. There is no likelihood that the US, or any other conceivable single-state power, could establish lasting control, even if it wanted to (Hobsbawn, 2002).

The major difference between the twenty-first and the twentieth century is ‘the idea that war takes place in a world divided into territorial areas under the authority of effective governments which possess a monopoly of the means of public power and coercion has ceased to apply’ (Hobsbawn, 2002). The dissolution of the USSR and the European Communist regimes has increased the instability of the international system.

The succession of US wars in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries -–Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria—represent the peaks in deaths in the postwar period although the number of war deaths has been declining since 1946.2 They have involved massive US investment in the ‘military-industrial-academia’ complex and millions of civilian deaths. The US military budget, the largest in the world by far, exceeds China 3-to-1 and Russia 10-to-1. US Federal spending was $4.7 trillion of $22.4 trillion economy. Military budget was $726 representing 10% of entire US spending, approximately 3.2% of GDP. US State and local expenditure represented another $3 trillion comprising almost 35% of US GDP. US national defence spending averaged 5–10% of GDP during the Cold War but both Israel and Saudi Arabia had higher proportional spending (O’Hanlon, 2019).

Democracy—its theory, practice and educational applications—has been a favoured topic for philosophers of education ever since Dewey’s (1916) Democracy and Education even although it rarely matched reality. Few would argue that empirical studies of democracy should inform philosophy of education and that philosophy is not a purely conceptual pursuit with no relations to existing states of affairs in the world. Democracy is globally in decline during 2020–21 representing some disturbing trends. The major survey instruments all indicate that globally democracy is deeply in trouble and losing ground. The Index of Democracy compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) evaluates the state of democracy in 167 countries based on 60 indicators measuring pluralism and electoral processes, civil liberties, functioning of government, political participation and political culture. The Index categorizes countries into: full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid regimes and authoritarian regimes.3 According to the EIU in 2020, there were 23, 52, 35 and 57, respectively in each of the categories. Democracies made up less than 50% of all regimes. The USA was ranked at number 25 as a flawed democracy and the United Kingdom was ranked at 16th, with Norway, Iceland, Sweden, New Zealand, Canada, Finland, Denmark, Ireland, Australia, Netherlands, in order taking the first ten places—all essentially countries predominantly euro-centric with small populations but with multicultural and immigration problems. One of the biggest changes was the downgrading of the US to a flawed democracy after 2016 and the election of Donald Trump. The Hindu nationalist government under Narendra Modi cracked down on dissent and restricted citizenship to Muslims, dislodging India from ‘Full democracy’ to ‘Flawed democracy. India has had to renounce its claim to global leadership on the democratic front with a reversion to narrow Hindu interests that sacrifice both inclusiveness and equal rights for all. During the second decade of the twenty-first century, the EIU reports indicated ‘Democracy in retreat’, ‘Democracy under stress’, Democracy at a standstill’, ‘Democracy in limbo’, ‘Democracy in an age of anxiety’, ‘Revenges of the “deplorables”’, ‘Free speech under attack’, ‘A year of democratic setbacks and popular protests’, ‘In sickness and in health?’. Given these national populist movements and their illiberal effects, one has to wonder about the new US foreign policy emphasis on human rights as the spearhead of an internationalist promotion with attacks on ethnic and religious minorities in both India and the US. It simply does not match the downgrading of democracies in these countries.

Freedom House Democracy Index 2021 is headed ‘Democracy under Siege’ and Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz write:

The impact of the long-term democratic decline has become increasingly global in nature, broad enough to be felt by those living under the cruelest dictatorships, as well as by citizens of long-standing democracies. Nearly 75 percent of the world’s population lived in a country that faced deterioration last year. The ongoing decline has given rise to claims of democracy’s inherent inferiority.4

They indicate a growing democracy gap after 15 years of decline and they comment on the serious significance of Trump’s presidency for the slide of world democracy as follows:

The parlous state of US democracy was conspicuous in the early days of 2021 as an insurrectionist mob, egged on by the words of outgoing president Donald Trump and his refusal to admit defeat in the November election, stormed the Capitol building and temporarily disrupted Congress’s final certification of the vote. This capped a year in which the administration attempted to undermine accountability for malfeasance, including by dismissing inspectors general responsible for rooting out financial and other misconduct in government; amplified false allegations of electoral fraud that fed mistrust among much of the US population; and condoned disproportionate violence by police in response to massive protests calling for an end to systemic racial injustice. But the outburst of political violence at the symbolic heart of US democracy, incited by the president himself, threw the country into even greater crisis. Notwithstanding the inauguration of a new president in keeping with the law and the constitution, the United States will need to work vigorously to strengthen its institutional safeguards, restore its civic norms, and uphold the promise of its core principles for all segments of society if it is to protect its venerable democracy and regain global credibility (ibid.).

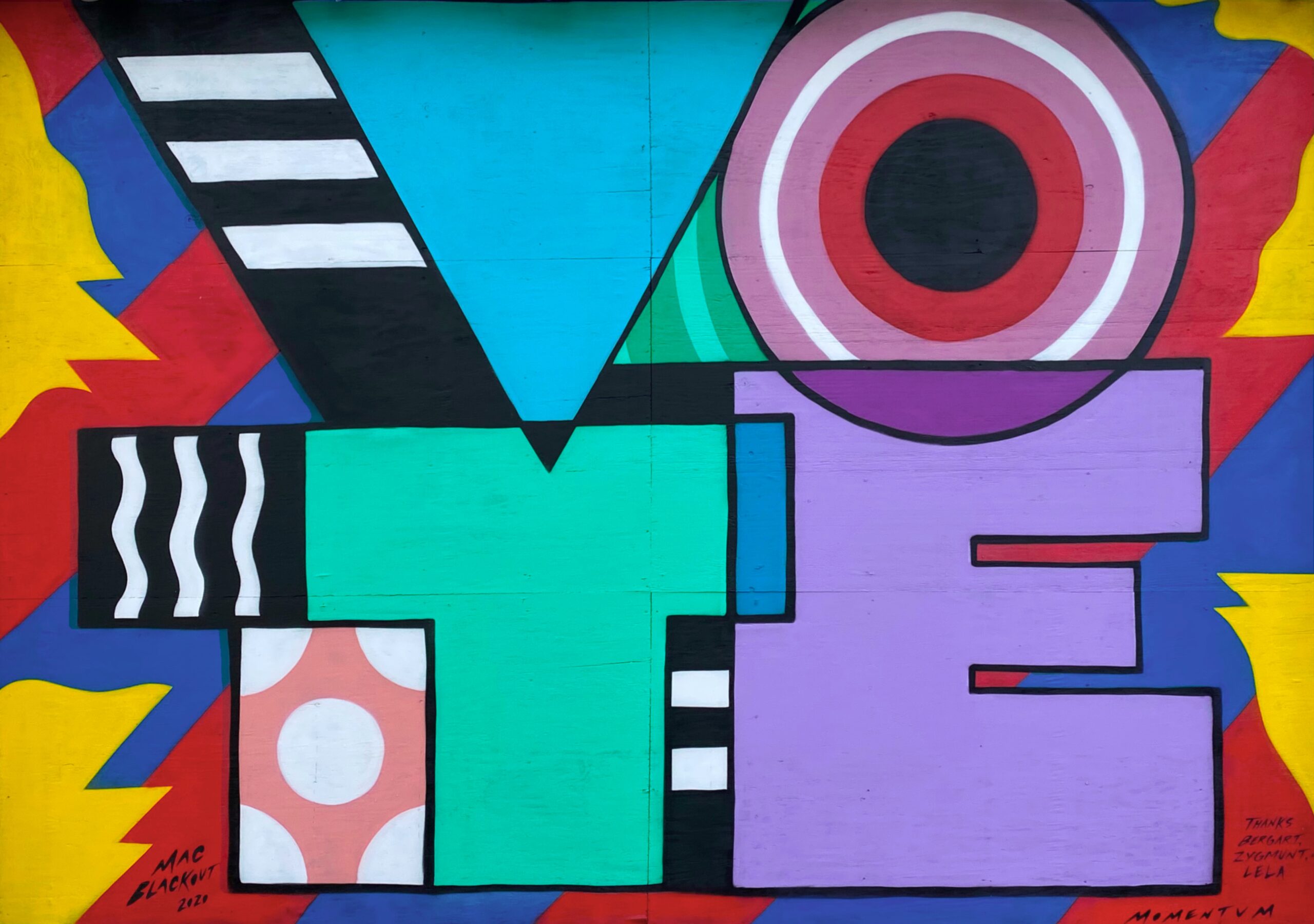

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement has revealed the true extent of internal division that reflects the historical conditions of the Civil War, with white supremacists wanting to revisit the appalling racism of the Confederacy and Old South. US politics and media now knows little common ground as the project for national unity withers away with Republican Party’s comfortable embrace of Trump’s racist and divisive policies including the recent attack on Black voting rights. What is more, Critical Race Theory and Critical Pedagogy are now pilloried by Republications who are seeking legislation to prohibit their use and mention in American schools, influencing states to propose legislative bans on anti-racist teaching.5

The hope that greeted the so-called Arab Spring in the 2010s that was a series of anti-government and for-democracy protests quickly dissipated after 2012 were met with violent responses from dictators and autocratic regimes or through continued civil war and occupation. As of 2018, only Tunisia made progress in terms of democratic governance but most recently, in 2021 Magdi Abdelhadi, reported that it stunned the world on…

25 July, when the secular President Kais Saied stunned the world by announcing the suspension of parliament, the sacking of the cabinet and assuming emergency powers citing an imminent threat to the Tunisian state. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-58071263.

By 2021 in Syria multiple conflicts have caused massive economic hardship and dislocation. The Arab Spring led to the Arab Winter and while there are continuing protests, anti-government activity has led to increasing sectarianism and growing state instability.

Philosophy of education needs to acknowledge these developments if it is to accurately reflect unfolding events. If it wants to philosophize about the benefits of democracy in education, then it must start by recognizing the state of peril faced by world democracy. It must take on board the empirical reality of a world no longer built for democracy, democracy promotion or even largely comprised of democratic regimes. It is not absurd to contemplate the end of liberal democracy (McKay, 2019). Martin Wolf (2020) writes of ‘The fading light of liberal democracy’ and begins by referring to Timothy Garton Ash’s essay ‘The Future of Liberalism’6: ‘For the first time this century, among countries with more than 1 m people, there are now fewer democracies than there are non-democratic regimes.’7 Ash makes the following plea very much in tune with this invitation:

Writers have interpreted the failings of liberalism in different ways; the point, however, is to change it. Self-criticism is a liberal strength. The very fact that there are already so many books diagnosing the death of liberalism proves that liberalism is still alive. But now we must move from analysis to prescription.

There are many types of democracy apart of liberal democracy, including authoritarian, conservative, deliberative, direct, grassroots, Jeffersonian, majoritarian, multiparty, national, participatory, procedural, radical, representative, religious, socialist, totalitarian, and workplace, to name some well-known types. The link between liberalism and democracy must be carefully studied and it must be analysed empirically to see whether the connection is merely contingent.

Philosophers of education need to address the historical reality of the ‘fading light of liberalism’; they need to learn from their colleagues in history and in the social sciences; they need to weigh the evidence and advance new analyses that led to educational prescriptions on the pain of risking irrelevance. We can no longer go on analysing concepts and pretending that nothing has changed since the apex of the West in the 1960s (and the preceding century) when philosophy of education underwent the first revolution.

An invitation

This call is for 3000 word papers suitable for publication as a Column in PESA AGORA at https://pesaagora.com/. Please follow the PESA AGORA house style with limited references (no more than five) and conversational style. Papers may also be chosen to be published in Educational Philosophy and Theory. To answer this call, please submit an abstract of 250–300 words to Tina Besley (admin@pesaagora.com) and/or Michael Peters (mpeters@bnu.ac.nz) by September 30th.

Guiding questions

How much does it cost to make the world safe for democracy?

Does democracy at home necessitate war abroad?

What is the history of liberal democracies in terms of conflict around the world?

Is it the end of liberal democracy and liberal education?

How deeply implicated are universities in the ‘military-industrial-academic’ complex?

To what extent are schools incorporated in training for war?

Is there an effective global authority capable of controlling or settling armed disputes?

To what extent has Cold War assumptions and institutions failed to ensure global peace or promote democracy?

Is the US economy a war economy and does it require war to prosper?

Is war and conflict an inevitable part of the human condition?

What is your prognosis for war in the twenty-first century?

Can education make a difference?

Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, PR China

Department of Education, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, PR China

epat.journal@gmail.com http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1482-2975tbesley@bnu.edu.cn http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4377-1257

Notes

1 https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/timeline-of-20th-and-21st-century-wars; see also https://www.scaruffi.com/politics/massacre.html

2 https://ourworldindata.org/war-and-peace

3 https://www.eiu.com/n/ and https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2020/

4 https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2021/democracy-under-siege

5 https://www.vox.com/22443822/critical-race-theory-controversy

6 https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/the-future-of-liberalism-brexit-trump-philosophy

7 https://www.ft.com/content/47144c85-519a-4e25-9035-c5f8977cf6fd