Claiming to represent the apogee of Western democracy, the United States has undertaken grievous crimes against humanity throughout the course of its history, and I don’t need to itemise all of the egregious episodes pertaining to imperial interference in the elected governments of countries and the waging of wars considered to be threats to world peace. This must be admitted from the outset. Does this mean we can’t trust Western democracy? Or that it doesn’t exist? Or that Western geopolitical worldviews must be cast into the dustbin of history?

At the same time, we must acknowledge that there are rule-driven universal standards related to human rights, albeit those developed throughout Western history, that are worthy of admiration and even binding international agreement. It is in the spirit of defending the idea of democracy and universal human rights that we must examine the recent joint statement issued by the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on ‘International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development.’ It is a short yet grandiose document that challenges the balance of power in today’s world. Not only is the US pivot to Asia facing a formidable barrier, but the statement also constitutes a fundamental challenge to Western modernity itself. Clearly, this document must be understood within the context of Russia’s relationship with Ukraine and China’s relationship with Taiwan.

However, my comments pertain to its implications for the current war in Ukraine. In this world-historical document, two worldviews are clearly delineated. The statement overall reflects a commitment to a multipolar world and an alliance (Russia and China) that seems to have no limits in terms of areas of cooperation and support. The document rejects the idea of a unipolar ‘hegemon’ that imposes its own desires on a world of many cultures, customs, political arrangements, worldviews and governing practices, a hegemon that is a dangerous threat to global and regional peace (with obvious reference to the United States). It is, for example, unsurprisingly critical of the AUKUS alliance in the Indo-Pacific region (the United States’ Indo-Pacific strategy) as threatening the peace and stability in the region.

But the surprise to me was the importance that China and Russia placed on democracy. Soon, however, it became apparent that the concept of democracy they are referring to does not bear much similarity to how we, in the West, would define it. By maintaining that ‘[t]here is no one-size-fits-all template to guide countries in establishing democracy,’ and that every country must ‘respect the rights of peoples to independently determine the development paths of their countries’ the statement effectively is proclaiming a democracy that resembles an empty container into which any and all situations may be shovelled and still bear the name ‘democracy.’ It could mean the right to choose any type of government and claim it to be a democracy, just not a Western-style democracy. In this tradition, Sakwa says, ‘Putin has always considered himself a democrat,’ and the document insists that Russia and China are ‘world powers with rich cultural and historical heritage [that] have long-standing traditions of democracy.’

An extreme version of the Russian argument might go something like this: We demand the right to call whatever political arrangement we want to be a democracy – even if you Westerners consider it to be totalitarian or fascist! It’s just a clash of civilisations, you know! You can’t monopolise the meaning of democracy! If it looks like fascism to you, well, we are telling you that it’s our version of democracy. It’s our way of giving citizens the ‘means’ to implement a ‘popular government’ ‘with the view to improving the well-being of the population,’ as the joint statement has it. If you call it martial law, then that’s just your opinion of our democracy; we have our own unique Slavic practice of democracy; what you are criticising is just our unique way of trying to improve the well-being of the people. We have our way, and you in the West have your way. There are multiple modernities, and ours happens not to be Western. Don’t be such an epistemic imperialist! We know what you did with the indigenous cosmovisions of your native peoples!

Well, it’s not that simple. The document seems as though Putin’s Rasputin, Aleksandr Dugin, may have had a hand in writing the document. As I have previously mentioned, Dugin is one of the world’s most dangerous Christo-nationalists, a man who admires the Roman Empire and its medieval European successor as one of the best models for combating liberal modernity since it exalts the triumphs of monolithic white, Christian nationalism, glorifies the union of the church and state, and adopts a political vision of a multipower political arrangement that envisions Russia recapturing its lost empire while becoming the head of a resplendent Eurasian Union. Dugin sees modernity and the Enlightenment tradition and its current pitbull, the United States, as essentially the product of a rootless and materialist society fallen from grace, and seeks a remedy in a jumble of gnostic doctrines.

Ted Snider points out that the joint statement represents ‘a really low bar that Western democracies would never accept.’ Snider refers to comments made by Richard Sakwa, who maintains that Russia and China are appealing to ‘an underlying principle … of “multiple modernities” … that there are different ways of being modern – not necessarily Western.’ There is no doubt that international relations predicated on a Western worldview are being fundamentally and vociferously challenged by this joint document. On the other hand, have Western democracies had a good track record in upholding rules-based international relations? Ask the people of Chile, Vietnam, Cambodia, El Salvador, Brazil, and many other countries what they think of American diplomacy during the 1970s? And what about Iraq and Afghanistan? Egregious abrogation of international law does not necessarily mean that the law itself has little or no validity or potentiality. But in the China/Russia document, if ‘each country can choose its fit of democracy, taking into account its social, political, historical and cultural background and that only the people of the country can decide whether their country is a democracy,’ then the value relativism here overwhelms universal standards and not only makes democracy too fluid to stand for anything of substance, it dissolves it like vodka in a paper cup left on the roof of a dacha in a rainstorm.

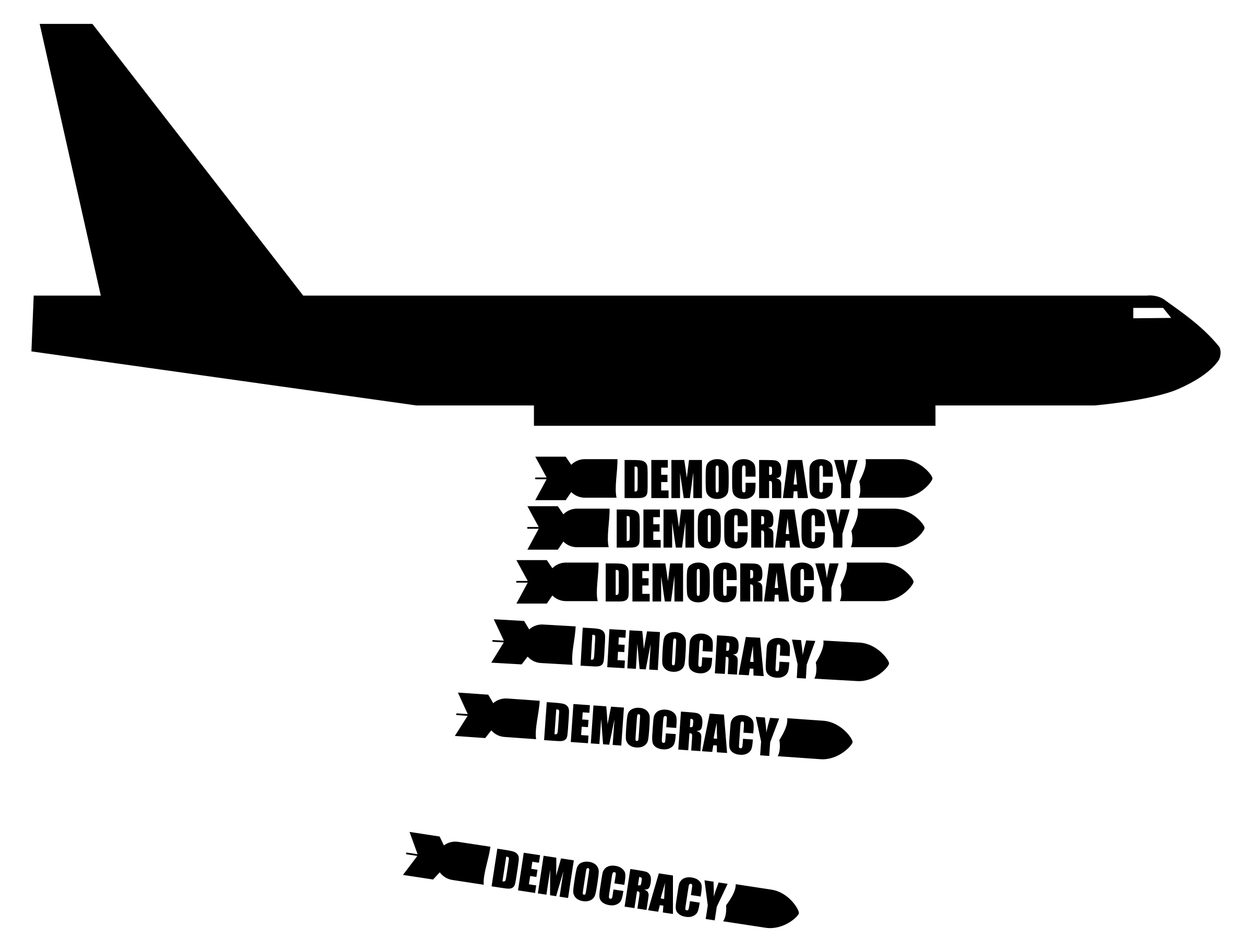

Snider makes some good critiques of US democratic principles as applied between nations when he writes: ‘Biden has defined his administration by the generational struggle between democracy and autocracy. The US compels democracy upon countries. Hence, the embargo on Cuba cannot be lifted until Cuba becomes a multi-party democracy. But Washington also insists on maintaining a unipolar world in which democracy is denied between nations and the US rules as an autocrat.’ Is it any wonder that ‘Russia and China have recently begun subscribing to the idea of ‘democratisation of international relations,’ in which all nations have an equal voice? On the contrary, the US has always hypocritically demanded democracy for each nation while insisting on its unique autocratic role at the international level.’

Paul Mason is not optimistic about a document that not only proclaims, but univocally asserts, that the ‘rules-based international order [is] over.’ Mason offers two statements that Western diplomats will not like to acknowledge; first, that

NATO, along with the United Nations and the European Union, may choose to go on affirming that its goal is to maintain a rules-based order, but reality is no longer rules-based. Though there is much to despise in the ‘realist’ school of international relations – with its pre-globalisation assumptions of taken-for-granted ‘national interests’ – we are at a moment where realism, in the sense of cool objectivity, is at a premium.

Secondly, he notes that, whether the Western political bureaucrats like to admit it or not,

The international system is not just broken but fractured in a manner unlike ever before. The great-power system which collapsed in 1914 was a complex balancing act among at least six states: Britain, the US, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia and Japan. Even the great duel of the mid-20th century, between the ‘axis’ and the ‘allies,’ was a mosaic of different wars and rivalries. In both cases, war was a result of an interregnum in which a declining power was losing grip, but its rising replacement could not exert control.

In effect, Mason is arguing that the world needs to acknowledge that there are three rival modernities that history is forging and consolidating into semi-permanent blocs: ‘western democracy, Chinese totalitarianism and Russian totalitarianism, the latter two in a strategic alliance.’

Russia has an adversary, and it is NATO. That’s official and has been so since the collapse of the Soviet Union. So, how are we to conceptualise the relationship between Europe and the US? How do we consider this alliance that has been brow-beating each other for decades? Mason has an answer: ‘The second big piece of reframing has to involve European ‘strategic autonomy.’ This follows from the Zeitenwende (historical turn) declared by the German Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, where Europe would arrange its own security with Russia, and it is a position supported by Macron. Before Putin attacked Ukraine, the EU needed some type of strategic autonomy because the US appeared unreliable as an ally while at the same time, ‘the European powers needed to ‘take the strain’ from America in deterring Russian aggression.’ But Russia’s two draft treaties with NATO and the US, ‘which Putin slapped on the table in December,’ altered the situation in a serious way. Mason argues that the US must remain actively engaged in the defence of NATO’s eastern flank for the foreseeable future. The EU must take a back seat to NATO in this regard.

A lot will depend on whether Sweden and Finland will join NATO. If they do join, Mason argues, ‘We will have Norway, Portugal, Spain, Germany, Finland and Sweden led by the centre-left and even centre/radical-left coalitions.’ NATO must remain a defensive alliance and not try to encircle Russia. And Ukraine should be offered a binding security guarantee from NATO’s major powers without officially joining NATO. Mason raises the issue of Russia’s ‘projection of ‘soft power’ into Russia and the negation of Putin’s hybrid-warfare offensive against western democracies.’ In this case, Mason rightly affirms that NATO cannot engage in ‘regime change’ but Europe’s progressive parties can, and should, support the forces that uphold democracy and the rule of law in Russia (including those who are protesting the war in Ukraine in the streets of Moscow). While ‘regime change’ cannot be NATO’s goal, it should, Mason notes, be the stated aim of Europe’s progressive political parties to help reinstate democracy and the rule of law in Russia. In any case, Russia must be deterred from attacking its NATO neighbours. This will entail the expansion of NATO military forces, according to Mason.

Mason’s overview assumes, of course, that Putin will not deploy his arsenal of nuclear weapons. But that’s a bold assumption. Assuming that the war is still being fought in Ukraine in some form or another in two years’ time, we need to take into serious consideration that either Trump or DeSantis will win the US presidential election in 2024. Judging from the political situation at the moment, Trump could very likely win. At present, NatCons in the US have shifted from supporting Putin and are siding with Ukraine (at least as long as it seems politically expedient for them to do so). But that could change if Trump or DeSantis wins the presidency, assuming the world is not a giant hunk of smouldering cinder by that time. In their recent Brussels meeting, the NatCons claimed that they support Ukraine because Ukraine supports their anti-Western values. When Ukraine proves to be too pro-liberal democracy, the NatCons will turn to Trump. Trump would weaken NATO, perhaps break from it entirely, thereby destroying whatever advantages Europe’s pursuit of strategic autonomy had achieved. It would be an absolute nightmare for the world. Trump would likely pull out of the collective-defence agreement known as Article 5. Remember that Trump made an exit from Syria, and now Russia happily controls that region. Trump was impeached because he held up defensive weapons for Ukraine in an attempt to force Zelenskyy to announce an investigation into Hunter Biden on baseless charges of corruption. Trump has a memory for grudges. Remember ‘Person. Woman. Man. Camera. TV’? In any case, Reps Marjorie Taylor Greene and Madison Cawthorn, who have described Zelenskyy as a ‘thug’ and ‘corrupt,’ won’t let Trump forget, assuming these two clowns are still in the government in 2024.

The tide could quickly turn against Ukraine. Which would be a tragedy.