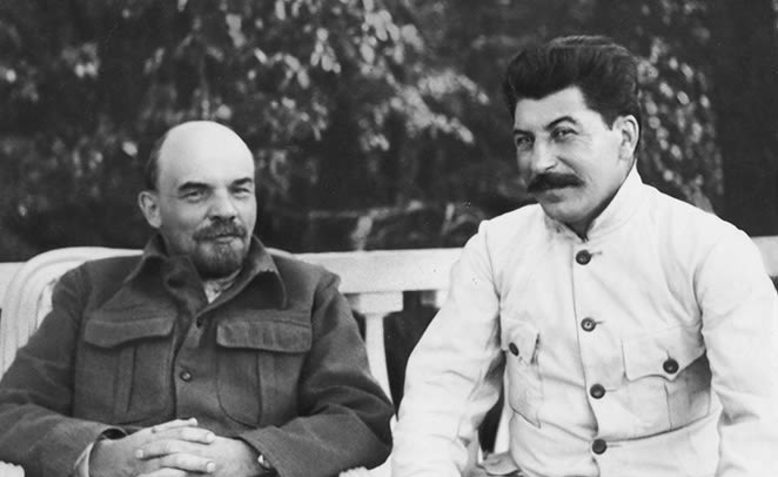

The war in Ukraine cranks on. Contrasted with Zelenskyy’s stingingly lucid utterances-at-large, we can only gaze in bleak comprehension at the mirror-like surface of Putin’s mind as he continues to peddle his brand of gloomy nationalism delivered in a cliché-ridden orderliness that seems irreverently detached from reality and fortified by an indispensable quota of self-deceit. With all the talk by Putin that Ukraine does not merit the status of an independent nation, it is worth remembering that the positions taken by Lenin and Stalin on the national question were diametrically opposed and fiercely so. Lenin, for all his mistakes, was a brilliant revolutionary thinker and more acutely aware than most revolutionaries of the consequences of ignoring issues of national identity, language and culture. He was certainly up to the challenge of consolidating support for the revolution among many different nationalities and understood that the best way to forge the Soviet Union was through the union of free and equal Soviet states. However, he was hampered by a stroke in March 1923. He was stiff with right-sided hemiplegia and speechless. At 51 years old, he had difficulty maintaining his usual pace of work. After Lenin’s death in January 1924, an autopsy showed that Lenin’s multiple strokes were due to severe atherosclerosis of his cerebral arteries, which were discovered to be almost blocked. The large blood vessels in Lenin’s brain were stiffened by atheromatous plaques, likely a genetic component that accounted for multiple severe atherosclerosis cases in this family.

A totalitarian leader such as Stalin supervenes when he is allowed to conduct a life of the mind without being rational, sacrificing a principled politics for a rule by terror and displaying, with cold calculation, ideas uncongenial to a merciful brain, while at the same time demonstrating an inexplicable grandeur pertaining to the level of power to which he has aspired and miraculously achieved. Lenin was able to see beyond the perils of the politics of imposition when it came to the question of culture and nationality. The inextinguishable tension between these two ill-matched giants of history was fiercely palpable. Lenin did not agree with Stalin’s rigid definition of a nation as an ‘historically constituted, stable community of people, formed on the basis of a common language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a common culture,’ which would have ruled out the rights of many peoples, most notably the Jews’. Lenin put together his principles as follows:

The proletariat cannot but fight against the forcible retention of the oppressed nations within the boundaries of a given state, and this is exactly what the struggle for the right of self-determination means. The proletariat must demand the right of political secession for the colonies and for the nations that ‘its own’ nation oppresses. Unless it does this, proletarian internationalism will remain a meaningless phrase; mutual confidence and class solidarity between the workers of the oppressing and oppressed nations will be impossible.

According to Zizek,

Lenin remained faithful to this position to the end: immediately after the October Revolution, when Rosa Luxembourg argued that small nations should be given full sovereignty only if progressive forces would predominate in the new state, Lenin was in favour of an unconditional right to secede. In his last struggle against Stalin’s project for a centralised Soviet Union, Lenin again advocated the unconditional right of small nations to secede (in this case, Georgia was at stake), insisting on the full sovereignty of the national entities that composed the Soviet state – no wonder that, on September 27, 1922, in a letter to the Politburo, Stalin accused Lenin of ‘national liberalism.’

The Bolshevik government was creatively involved in governing a multi-ethnic state. Under Lenin’s influence, it created tens of thousands of national territories, established national languages, and financed the production of much national-language cultural merchandise. Stalin, however, wanted to build socialism in Russia alone. And while Stalin proposed that the independent Soviet republics of Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia be established as autonomous regions within the Russian Federation, he insisted all key functions of the government be undertaken by the Russian ministries, while allowing minor decisions around culture, justice, healthcare and land to be left in the hands of the autonomous regions. Stalin pushed his plan through, even at the objection of nearly all of the republics. Lenin became incensed and demanded the USSR be a federation of equal republics. Unfortunately, Stalin’s Great-Russian chauvinism prevailed after Lenin’s death:

The use of the Baltic states as pawns in negotiations with Hitler, the deportation of whole nations, including the Chechens and Crimean Tartars to Kazakhstan during the second world war, the use of the Soviet army to put down uprisings in the former East Germany, Hungary and Czechoslovakia and the refusal to recognise nation rights during the period of ‘perestroika’ had absolutely nothing in common with the national policy of Lenin and the Bolshevik party.

Self-determination of peoples still remains a vital challenge among those committed to a socialist future and should not be subordinated to a socialist bureaucracy, which is why it is vital to support the self-determination of the Ukrainian people and not believe Putin’s crazy excuse that his ‘special operation’ in Ukraine is all about demilitarisation and denazification. Or that Ukraine is a fascist state.

According to Rob Jones,

[t]he Bolsheviks … led by Lenin bent over backwards to support the rights of national and ethnic minorities. Way ahead of his time, Lenin even criticised the use in everyday language of national stereotypes such as the use of the word ‘Khokhol’ to describe Ukrainians. Not only is this word still in widespread use, but it was also added to recently by official Russian propaganda, which presented the Ukraine as a fascist state.

In fact, ‘Lenin spoke against the recognition of specific languages as ‘state languages,’ particularly when that meant that significant language minorities were discriminated against.’ Jones continues: ‘Even the threat of restricting the use of Russian in Ukraine was enough to heighten the tensions that led to the conflict in East Ukraine. Hypocritically, the Putin government, which used the attack on the rights of Russian speakers in Ukraine to intervene in East Ukraine, has now announced that finance for the teaching of Russia’s many minority languages will cease.’ Jones writes that

Lenin would get quite angry when he heard that soviet officials, including those from the centre, continued to use Russian in those areas where Russian was not the local language: ‘Soviet power differs from every bourgeois and monarchical power in that it represents the real daily interests of the labouring masses in full measure, but that is only possible on the condition that soviet institutions work in the native languages.’ Unfortunately, one of the worst barriers to the development of national languages was the Nationalities ministry itself, whose officials often argued that it was sufficient to just translate from Russian into local languages. Lenin replied that, on the contrary, the task was to ensure that educational authorities provide teachers familiar with native languages and cultures as well as native language textbooks.

Jones writes,

In Ukraine, much effort was spent, and much patience was needed to work with the ‘Borotba’ organisation, essentially a left-social revolutionary grouping with roots in the countryside. Christian Rakovskii, a long-time friend and ally of Trotsky, played a key role in this work. At the same time, ten new ‘communist universities’ were established to train national Bolshevik cadres. As importantly, a huge investment was made in opening the public education system for teaching in the national languages. Ten million roubles were allocated in 1921 to further the teaching of Belarussian and Ukrainian languages.

Lenin continued a ‘sensitive and flexible approach’ to the different nationalities, and, while

the Bolsheviks were in favour of the voluntary collectivisation of land, Lenin warned that in regions such as Central Asia and the Caucasus, it would be premature to push the issue. He even argued against the nationalisation of the oil industry in Azerbaijan, fearing that, as the working class were not yet developed enough, it would lead to the disruption of supplies during the civil war.

Should we identify Lenin as one of the first revolutionary multiculturalists? Or should that honour be given to Karl Marx himself? Lenin did not have access to Marx’s unpublished 1879–82 notebooks, in which, as Kevin Anderson brilliantly argues in his canon-changing work, Marx at the Margins, Marx presents himself not as an exclusively class-based thinker but a global theorist extremely sensitive to issues such as nationalism, race, and ethnicity.

The idea of a multi-ethnic state that Lenin proposed has been put forward in the United States. And their proponents have been met with a fury of condemnation. It is something I am very familiar with, having dealt with the Tea Party for years, and the Freedom Caucus and those who comprise Trump’s base of supporters. I am sure Lenin would recognise the ethnonationalist, anti-globalist Republicans for who they are, with their attacks on voting rights and on women’s bodies, their assaults on democracy, their banning of books, their legislating-away of the right to teach the history of slavery, their attempt at a coup on January 6, 2020, not to mention their love affair with the Christian right’s theocratic doctrines. I’m used to their McCarthyite-sounding attacks, their attempts to bring back a Jim Crow era – but victims who suffer the most from these vile agendas are African Americans, people of colour. Recently, in the US, a white 18-year-old male fatally shot ten people and injured three others at a Buffalo supermarket in the heart of the city’s Black community. He had travelled from another New York county hours away. Thirteen people – 11 of whom were African American – were shot. The suspect had posted a manifesto complaining about The Great Replacement Theory – about the ‘dwindling size of the white population and claims of ethnic and cultural replacement of whites’ by people of colour.

You know how that story goes. I’ve listened to and written about white folks who have complained about this for years. As someone who was writing about multiculturalism with comrades decades ago, and then revolutionary multiculturalism, it is interesting to see how debates over the national question were dealt with by Stalin during the creation of the Soviet Union. Florida’s governor Ron DeSantis would certainly have been on the side of Stalin. After all, who needs democracy when we can create a fascist, totalitarian regime – powered by state capitalism, no less.

As early as 1918, Stalin was arguing that ‘the slogan of self-determination is outmoded and should be subordinated to the principles of socialism,’ believing that Russia should be indivisible and that the issue of subordination be treated with a heavy hand. And, of course, Stalin’s view prevailed right up to the time of the Great Patriotic War, when Russians, Ukrainians, Georgians, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Armenians, and others joined together with Stalin, ‘the father of nations,’ to fight Hitler and his world-destroying death machine. Yes, Stalin’s strongman leadership did help the Soviet Union win World War II.

During that time, my father had joined up with the Royal Canadian Engineers and fought the Nazis in Italy and Holland, and my uncle joined the Royal Navy, where he flew off the Ark Royal in his Fairey Swordfish (a fabric-covered biplane torpedo bomber) and is credited with putting the torpedo in the Bismarck battleship (for which the Distinguished Service Cross was pinned on him by King George VI (yes, the King with the stammer). I am sure both family members, while anti-communists, appreciated the role that the Soviet Union led by ‘Uncle Joe’ played in defeating the most brutal regime in world history. At the same time, I am old enough to remember my conservative father talking about Soviet tanks and troops rolling into Hungary on November 4, 1956. And I remember, only too well, the date, August 20, 1968. That’s when the Soviet Union led Warsaw Pact troops in an invasion of Czechoslovakia to crush the Velvet Revolution protesters in Prague. And how many readers recall the millions of protesters across Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania participating in what came to be known as the Singing Revolution when they formed a 370-mile (600km) human chain across the Baltic republics calling for independence? And I remember visiting Poznań, not the Poznań protests of 1956, but a visit there and other Polish cities after the Fall of the Soviet Union, where I was gifted with some original pamphlets created by the Solidarity mass movement in the Polish People’s Republic that challenged the rule of the Polish United Workers’ Party and Poland’s alignment with the Soviet Union. As a Marxist humanist who has spent considerable time in Latin America and who is a founding member of Instituto McLaren (supported by el Partido de los Comunistas Mexicanos of which I am an honorary member) and who spent time in Venezuela on behalf of Hugo Chavez’s Bolivarian Revolution, I was never a Stalinist, and have found the International Marxist Humanist Organization to be most compatible with my own political formation.

Hatherley describes the clash between Lenin and Stalin as follows:

In his frothing, disgustingly self-pitying speech a few days ago, Vladimir Putin blamed the existence of Ukraine on Vladimir Lenin. He blamed it upon Lenin’s insistence in the early 1920s that Ukraine, like all republics of a Soviet Union, should have the right to autonomy, the right to its own language, and the right to secede – over the objections of the ‘Great Russian Chauvinists’ among the Bolsheviks, and causing a deathbed battle with Stalin.

It is sometimes claimed that Lenin did this as more Realpolitik, as some means of committing smaller nations – some of which, like Ukraine, became briefly independent during the Civil War of 1918–21 – to the Soviet project. Sure, that was some of it. But it was also a matter of principle.

You don’t have to be a Bolshevik to recognise that Lenin, for all his faults, took a principled stand when it came to imperialism. Lenin, the author of What is to be Done? – ‘was appalled by the way leftists and working-class organisations lapsed into support for their own imperialisms, whether Germans voting for World War I in 1914, English leftists sitting by as James Connolly was tied to a chair and shot in 1916, or Russian Communists lapsing into ‘Great Russian Chauvinism’ in 1922. Lenin insisted that ‘a free Russia is impossible without a free Ukraine,’ just as for him, British socialism was meaningless without Irish independence. As he put it in more colourful language: ‘The Great-Russian chauvinist is in substance a rascal and a tyrant.’ Lenin continued:

Internationalism on the part of oppressors or ‘great’ nations, as they are called (though they are great only in their violence, only great as bullies), must consist not only in the observance of the formal equality of nations but even in an inequality of the oppressor nation, the great nation, that must make up for the inequality which obtains in actual practice. Anybody who does not understand this has not grasped the real proletarian attitude to the national question; he is still essentially petty bourgeois in his point of view and is, therefore, sure to descend to the bourgeois point of view.

Yes, we can criticise Ukrainian nationalism during the 1940s, just as we should. It is imperative that we find fault with right-wing extremism in today’s Ukraine and in Eastern Europe in general, such as cautioning against reverence for Stepan Bandera, the Ukrainian leader of a rebel militia that fought alongside Nazi soldiers in World War II, whose men killed thousands of Jews and Poles while fighting against the Red Army and communists in the belief that Adolf Hitler would grant independence to Ukraine. But, as Hatherley notes,

Ukrainian nationalism in its far-right variant during the 1940s was exceptionally brutal, but always marginal outside of the far-western regions annexed by the USSR from Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. That nationalism had nothing to do with Ukraine’s independence, which was supported overwhelmingly in a referendum in 1991, in the aftermath of the August Coup in Moscow. Independence was supported across the country, from the Donbas to L’viv, because Ukrainians, whether their first language was Russian or Ukrainian, no longer wanted to be tied to a Russia descending into great-power nationalism. Who can say they were wrong?

Let’s not forget that the Act of Declaration of Independence was held in Ukraine on December 1 1991, in which an overwhelming majority of 92.3% of voters approved the declaration of independence made by the Verkhovna Rada on August 24 1991.

But here I am clouding some of the intricate historical relationships, so it is important to draw attention to the fact that the divide between Lenin and Stalin prior to 1921 when it came to the national question wasn’t truly absolute. This has been pointed out to me by Peter Hudis (personal communication). Hudis makes the important observation that Stalin’s book Marxism and the National Question (1913) was assigned to him by Lenin, who read and approved its publication. And Stalin’s definition of a nation that I have provided – an ‘historically constituted, stable community of people, formed on the basis of a common language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a common culture’ – is one that we can find in Lenin as well. So Lenin wasn’t always consistent in practising what he preached. And, while it is true that this definition restricts national self-determination to groups with a ‘common territory,’ which excludes the Jews, it is also true, as Hudis points out, that both Lenin and Stalin had spent years rejecting the Bund’s position on Jewish self-determination (Stalin’s chapter on the Bund in chapter 5 of the book was Bolshevik orthodoxy). Now it’s also important to emphasize that this position did imply not supporting the ‘rights’ of Jews, which the Bolsheviks strongly advanced. Stalin wasn’t against advancing socialism throughout the Soviet Union insofar as he understood that the Soviet Union (established in 1922) was only 40% Russian (population wise) and while he surely wanted to create ‘socialism’ in the whole of it, he knew where he wanted the power to remain focussed.

And while Lenin may have maintained a general principle in support of self-determination for all subject nationalities (with a few exceptions, the Jews) of the former tsarist empire, this wasn’t always practiced by him. Hudis makes the following important points: 1) While Lenin supported national independence or autonomy he did not support independent or autonomous Communist parties in what became the USSR, which stood in the way of many subject nationalities (including Ukraine) being able to have effective autonomy or independence. 2) Lenin supported spreading the revolution through the armed force of the red army, even when it violated the right to self-determination: his disastrous decision to invade Poland in 1920 is the clearest case of this (Stalin was appointed by him commander of the southern front of the assault). The Poles were not pleased of course and Pilsudski imposed a crushing defeat on Tunachevsky, and the Poles haven’t forgotten it since. And Hudis also reminds us

that the Donbas region became part of Ukraine only in 1922, on Lenin’s orders. Although, as Hudis again points out, I doubt that Putin fails to know this!

The rise of Stalinism, which by the 1930s had reintroduced the Russian language as the command language, opposed Lenin’s directives around the issue of language, culture and the national question. Putin today is essentially marshalling a dire directive bent on de-Leninising Russia, de-communising Russia, but appropriating some aspects of Stalinism that Trotsky and Lenin would have considered a betrayal of the revolution. Putin is, for instance, adopting the Stalinist notion of establishing the control centre of Russian power at the Kremlin, subordinating all questions of nationalism to Putin’s iron fist. Yet we make a serious mistake if we think Putin is trying to revive the old Soviet Union. Putin is not a communist – think of him more as a modern-day Tzar, but without a taste that would demand female members of his court be draped in a Frenchified sarafan, or men constrained in wool doublets. He does have a version of Rasputin, though – Aleksandr Gelyevich Dugin – the ‘clash of civilisations thinker,’ but lacking the macabre powers of hypnotism and mind control attributed to Rasputin (powers that would have made operatives in the top-secret MK-Ultra program run by the CIA salivate with envy).

Putin has forged a strong union with the Orthodox Church, and he is a traditionalist that seeks to create a Russian empire that can compete economically and militarily with the US and China in a multipolar world not dominated by the US. And his one major ace card is his nuclear stockpile and advanced delivery systems. Putin is a reactionary imperialist; we should not forget that. Let’s remember that from 1923 to the collapse of the Soviet Union, a Stalinist bureaucratic counter-revolution ‘reversed Lenin’s approach with a whipping up of Great Russian chauvinism. The Ukrainian revolutionaries in the Borotba group who were won over to Bolshevism by Lenin’s approach were physically liquidated by Stalin.… It was Stalinist bureaucratic handling of national minorities that led to the break-up of the Soviet Union.’ When the leaders of the collapsing USSR learned that Ukraine wanted to become an independent state, that was the straw that broke the back of a flailing, desperate regime.

I agree with Volodymyr Artiukh, a Ukrainian anthropologist, that Putin is intent on destroying any remaining vestiges of communism developed by the USSR, and he has no intention of creating a new hegemonic bloc. For Putin,

decommunisation means destroying this ‘affirmative action empire ‘that was the USSR. Putin wants to destroy the economic and national units that the USSR created throughout its history. He wants to essentially rebuild the Russian empire with one imperial centre. Not necessarily within the boundaries of the old, but with a similar power structure of one imperial centre resting on an oppressive apparatus without any hegemonic ideology that mobilises people from below. Hegemonic leadership implies concession to the partners in the hegemonic power bloc, as the Soviet Union did, making some concessions to the nationalities. Putin is not interested in hegemony. He’s interested in building this ‘vertical power’ that begins and ends with the Kremlin. This is a very different thing to the Soviet Union. You need only look at how Putin talks to his Security Council, like to schoolchildren who failed their homework assignment. Compared to that, the Communist Party was a shining example of direct democracy….

Artiukh describes the logic of empire that guides Putin and his elite group of accomplices:

If you listen to Russia’s officials and read their ideological manifestos, if you read people who interpret Russian foreign policy decision-makers in the Kremlin – they see these apocalyptic events coming. They see the world-changing to the core. They see that we live in the new world, and Russia needs to find its place; otherwise, it will be eaten by these predators, by China or the US. They’re reasoning along the lines of ‘we need to act now, it’s now or never, there is time, and it will either be glorious, or we perish.’ They also hope that they will join China in a sort of alliance. And they already need to mark their territory. The logic is: ‘There are seven bad years ahead, but then we’ll have our hundred years of empire.’ This is the frame of mind, if you read closely what the Russians are saying.

The expansion of NATO up to the border of the USSR has a major role to play, to be sure, in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but Artiukh seems to believe it was an indirect consequence:

the war in Ukraine is not a direct consequence of NATO expansion. It’s Russia’s proactive step to change, to break this structure of power relations in which Russia existed. It was not reactive in the sense of an immediate threat; it was a predator’s attack at the moment when, according to the Kremlin, the enemy was at its weakest. The diplomatic spectacle was a distraction.

The majority of Ukrainians elected Volodymyr Zelensky in 2019. At that time, he promised to end the war, which was raging in Donbas and which had killed thousands, and he was committed to not push on the issues of identity and language. But, as Artiuk notes,

a year into his tenure as a president, he changed direction. Initially, he was accused of being pro-Russian, accused of preparing to capitulate to Russia. But as essentially every president of Ukraine does, he tried to concentrate as much power as he could. He had to defeat his nationalist enemies, attract their constituency, and became this Napoleonic figure that balanced the Right and Left, pro-Russians and pro-Europeans, and at one of the turns, he got stuck in the pro-Western nationalist corner. And at this point, everything collapsed.

And then the invasion happened. And then Russian troops started to occupy Ukrainian lands and cities, attempting a scorched earth policy when it came to any markers of Ukrainian identity. Teachers are reporting that Russian soldiers have requested to see Ukrainian school curricula, especially history books, demanding that teachers speak to them in Russian. Russian textbooks are being sent to schools via email, tech-wiping past national identifications. What about those sweet signifiers that breathed Ukrainian air, that embodied the heartfelt melodies of Ukrainian folk tunes played on the bandura or the sopilka, or those chilly Fall evenings when grandparents told stories of The Iron Wolf or The Magic Egg. Those memories have now been forcefully resignified, freighted with new inverted meanings, which basically say that the parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts and schoolteachers that you loved were just a bunch of conniving Nazis that deserve extermination. That your president is a self-hating Jew; that your local politicians are Hitlerites. Are all those sweet memories of youth now rendered unto Cesar, who rules his empire from the Grand Kremlin Palace and the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour on the northern bank of the Moskva River. The reframing of historical events by Russia is attempting to erase the national history of Ukraine, ‘cleansing’ the minds of the young. Ukrainian men in Crimea, who graduated from Ukrainian schools, but who were recently told by their Russian teachers that Ukraine doesn’t really exist, are now fighting against their (imaginary) country of origin: ‘Those children who studied at school six to eight years ago – when they were between 11 and 13 years old – are now fighting against Ukraine. Citizens of Ukraine, unfortunately, fight against their country.’

In the US, erasing history or simply not teaching it is now a common tactic of many Republican governors. Simply eliminating the history of slavery, of Jim Crow, of the civil rights movement and demonising critically-minded teachers is now a common practice among Republican administrations. Ideas such as racial capitalism, Afropessimism, Afrofuturism and Critical Race Theory are provoking white fear, and have turned white parents against their schools and school districts. This is a lesson that has not been lost in Ukraine, whose citizens have been fighting for recognition since the Russian Revolution.

Artiukh leaves us with some advice that is well worth considering:

We need to pay closer attention to what Russian scholars have done. We need to think more deeply about how the Kremlin guys picture themselves, what they imagine is happening around them, and what may motivate them beyond what the West imagines is rational. Clearly, their goals and the way they work is different than we imagine. We need to pay attention to the internal dynamics in Ukraine-Russia relations. This is not something we know a lot about beyond the simplistic Western portrayal of the good democratic Ukraine versus the terrible authoritarian Russia or the evil Nazi Ukraine versus the eternally mistreated Russia. We need much closer cooperation with the Left in Ukraine, Russia, and the West, which has not been happening beyond occasional meetings. Because the Left is a bearer of some knowledge, limited knowledge, but some unusual and probably insightful knowledge about the situation. A lot of people on the Left in Russia and Ukraine will need concrete material help, and they need understanding, because the fog of war destroys rational and critical thinking, and you need to be patient with people who make mistakes and will make mistakes. It’s impossible not to make a mistake when bombs are falling, and your friends are dying.

Owen Hatherley is similarly sympathetic to the plight of Ukraine. The invasion is a war crime, he asserts, and it is difficult to disagree:

What is happening now, for all the blustering sentimentality of our leaders, is not like ‘brave little Belgium’ in 1914. It is the humiliation and punishment of a desperately poor country, one which has never economically recovered from the end of the Soviet Union, and which has faced a cruel, bloody, and allegedly ‘limited’ war (which has killed 14,000 people) for the last eight years. Its cities are, right now, being bombed by a large, rich, nuclear-armed petrostate led by an absolutely ruthless, hard-right government, one which came to power on the Western-applauded bombing of Chechnya back into the stone age. This invasion is a war crime, and a war crime is a war crime is a war crime.

While it is easy to agree with Hatherley and Artiukh, we must, on the other hand, consider the type of assistance we can render this struggling country whose brave citizens are fighting against a vastly superior military power. We cannot ignore what could be the making of World War III. A worldwide movement against militarism and the creation of an international socialist movement has never been more urgent. We need to support Ukraine without escalating the war. Can we have it both ways? Especially when the leader of the country with the most powerful nuclear military in the world has just threatened the world. Any solution seems to require that we thread a diplomatic needle that might be hiding in a haystack somewhere, but by the time we find it, it will be too late. We have long left the world of sabre-rattling. We are now rattling missiles whose capabilities for death are unimaginably imaginable now – since we have already seen what a small version of today’s nuclear ordinances can do – in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Consider this:

The two nuclear weapons dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki had an explosive yield of the equivalent of about 15 kilotons of dynamite and 20 kilotons of dynamite, respectively. In modern nuclear arsenals, those devastating weapons are considered ‘low-yield.’ Many of the modern nuclear weapons in Russian and US nuclear weapons are thermonuclear weapons and have explosive yields of the equivalent of at least 100 kilotons of dynamite – and some are much higher. One 100-kiloton nuclear weapon dropped on New York City could lead to roughly 583,160 fatalities, according to NukeMap.

Russia’s nuclear mimetic rival, the US, has, since the end of the Cold War, ‘modified its declaratory policy to reduce the apparent role of nuclear weapons in US national security, but has not declared that it would not use them first.’ It has developed a ‘counterforce option’ which involves the employment of strategic air and missile forces in an effort to destroy, or render impotent, military capabilities of an enemy force, particularly the enemy’s nuclear-capable forces. Consider this evaluation in the journal International Security (Harvard College and MIT):

In the past, technological conditions bolstered those who favoured restraint: disarming strikes seemed impossible, so enhancing counterforce would likely trigger arms racing without much strategic benefit. Today, technological trends appear to validate the advocates of counterforce: remote sensing, conventional strike capabilities, ASW, and cyberattack techniques will continue to improve and increasingly threaten strategic forces whether or not the United States seeks to maximise its counter-force capabilities. In this new era of counterforce, technological arms racing seems inevitable, so exercising restraint may limit options without yielding much benefit. Nuclear deterrence can be robust, but nothing about it is automatic or ever-lasting. Nuclear stalemate might endure among some pairs of states, and technology could someday reestablish the ease of deploying survivable arsenals. Today, however, survivability is eroding, and it will continue to do so in the foreseeable future. Weapons will grow even more accurate. Sensors will improve. The new era of counterforce will likely yield benefits to those countries that best adapt to the new landscape, and costs to those that fall behind. The first step in understanding these dynamics is to recognise the new strategic reality confronting nuclear powers today.

I’ll leave you now to shudder in peace. But, at the moment, we have the privilege of not having to shelter with our Ukrainian partners in the basements of factories and schools, as Russian artillery continues to shell civilian neighbourhoods, sending body parts skyward, adding renewable despair to the already apocalyptic world we call Ukraine.

If you are planning to join a protest movement, please note that you might be paying someone’s salary if your group is deemed part of a ‘super-strain’ of political violence. You’ll be helping to expand the Global Riot Control System Market, as revealed by William I. Robinson:

A recent report by Lloyd’s of London, a global insurance and financial conglomerate, warned that ‘instances of political violence contagion are becoming more frequent’ and headed towards what it terms ‘PV [political violence] pandemics.’ It identified so-called ‘super-strains’ of political violence. Among what Lloyd’s deems as these super-strains are ‘anti-imperialist’ ‘independence movements,’ social movements calling for the removal of an ‘occupying force,’ ‘mass pro-reform protests against national government[s],’ and ‘armed insurrection’ inspired by ‘Marxism’ and ‘Islamism.’

State responses to this ‘political violence’ are big business. According to a 2016 report, Global Riot Control System Market, 2016–2020, which was prepared by a global business intelligence firm whose clients include Fortune 500 companies, in the next few years, there will be a multi-billion-dollar boom in the worldwide market for ‘riot control systems.’ The report forecast ‘a dramatic rise in civil unrest around the world.’

For Republican politicians, Russian oligarchs not on the sanctions list, and just plain old American millionaire entrepreneurs out there and those who wish to capitalise on the chaos they are creating that makes possible the growth in resistance movements worldwide; you can count on weapons manufacturers, surveillance industries, and now ‘riot control systems’ to keep your bank account fluid. Add this to your portfolios. Maybe you’ll get placed on the list of families chosen to inhabit Mars when the world you destroyed is no longer habitable. I wonder if there will be abortion services offered on Mars, on the sly, of course. Even with a ramped-up imaginative empathy, it’s too early to imagine possible futures and too late not to imagine them. Because hastening a final reckoning is the reason Putin has sent his tank columns into the darkness of what he believes are illegitimate cities protected by non-beings. And we are looking ahead to a long and drawn-out war whose tactical contingencies make it unfixed, but whose likely endpoint makes it all too centred. Will Putin bring on the apocalypse, or will Ukrainians leap into revolutionary action and prevent it? It seems that the Ukrainians fighting behind the barricades have already grasped this harsh truth without flinching from it, and understand the existential altercation imposed upon them as wards of imperialist power. They are taking up the burden of defending a future of hope at the very moment in which the very definition of hope needs resuscitation, obscuring the legitimating architecture of war that has been imposed upon them by a truth that can only be decided by violence.