Critical pedagogy is the bloomery in which educational swords are forged against injustice. This fire pit or furnace located in the smithy is ignited by the faithful, powering the cementation process that results in the blade. Oscar Romero, Paulo Freire and other important educational workers operate the bellows, and liberation theology delineates the battlegrounds where alliances between faith and politics are created, and what kinds of strategies and tactics will bring about the conversion of death into life. We, the social justice educators, are called to provide the anvil for curving and bending the steel around the bick and working the hardy and pritchel holes. Activists in the field are the bladesmiths who wield the hammer because they know the specific needs of the communities in which the struggles for liberation are being waged. If such an analogy seems overly violent, I would remind you of the sword of St. Michael and the spear of St. George. Those weapons weren’t only for decoration, and, yes, there is always a danger of what happens when weapons are employed by unholy hands. The stomach-churning massacres of campesinos throughout Latin America by death squads in the 1970s and 1980s, many of whom were trained in Fort Benning, Georgia, to our unending shame, were a lesson to us all that what might begin as culture wars – the culture of oligarchical rule and plutocracy – can end in decapitated bodies and severed limbs – just look at photos of bodies strewn about the streets of Bucha in Ukraine’s Kyiv Oblast, once the Russians made their exit. Didn’t Orwell warn us?

The theology of liberation that initially grew out of Latin American Catholic history was a profound spiritual reaction to new, progressive ecumenical positions taken by the Roman Catholic Church known as Vatican II. For decades, the Catholic Church had been extremely averse to social justice movements involving members of its ecclesiastic ranks, often associating such movements with communism. This was made tremulously clear in the anti-Communist encyclical, Divini Redemptoris, written by Pope Pius XI in 1937 that formalised the Vatican’s inevitable opposition against left-wing social movements, such as Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker Movement (ironically, Dorothy Day has recently been named ‘Servant of God’ by the Vatican and seems destined for sainthood).

Recognising the pressing need for the Catholic Church to reconsider its role in a changing world, including wider arenas where there was a need for spiritual renewal, Pope John XXIII challenged a recalcitrant Church to address the role of the Church in the contemporary world. His leadership was pivotal in forming the world-historical Second Vatican Council (famously known as Vatican II [1962-1965]). Pope John XXIII, through the 1962 Second Vatican Council, attempted to reclaim the early roots of the Church – that is, the Church of the first 300 years before it was recognised as the ‘persecuting Church’ that had infamously aligned itself with the Crusades and the Spanish Inquisition. Vatican II, followed by the Conference of Latin American Bishops held in Medellin, Colombia, a few years later, paved the way for a widespread acknowledgement of the historical alliances the Church had made with colonial powers and their empires of pillage and plunder – what we now call settler colonialism. The 1968 conference in Medellin marked the beginning of a seismic shift in the Catholic Church as it began to arc towards a concern for the beleaguered, the immiserated, and the suffering poor. It was here that bishops from all over Latin America agreed that the Church should take a ‘preferential option for the poor’ while developing a catechism of liberation undergirded by the teachings of Jesus so that the poor could liberate themselves from the ‘institutionalised violence’ of poverty and capitalist exploitation.

The late 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s had been especially brutal years for campesinos, workers, activists, teachers, and revolutionaries throughout Latin America, especially in the Southern Cone. The industrial developmentalist model that had been undertaken in Latin America since the 1950s was dependent upon richer nations and utilised a form of import substitution that gave advantages to the middle classes and some sectors of the urban proletariat but was overwhelmingly devastating to the peasantry. There was concern among many Latin American clergy that the growing poverty in Latin America, the expansive sweep of brutality at the hands of Latin American authoritarian ‘caudillo’ regimes, especially against left-wing organisations, and a growing political militancy among peasant groups, was leading to crisis situations that the Church was unable to address effectively either in theological or political terms. Michael Lee brilliantly describes how Vatican II (1962–65) became theologically and pastorally pivotal to the Latin American Church. Latin American bishops and those of the so-called Third World together had tried to inform the council of the pressing concerns of the Global South. Some bishops were not happy about the shift towards the poor or the social gospel ‘from below’ because they were concerned about the possible loss of the Church’s pre-conciliar identity and the diminishing emphasis on the Church’s Neo-Scholastic roots. But many other bishops welcomed these measures as a way that the Church could redeem itself as an inclusive institution by making ‘significant changes to the ways Catholics would worship, approach the Bible, and perceive (or conceive of) the church’s role in the world.’

The landmark gathering of Latin American bishops in Medellin (CELAM) would, Lee notes, ‘change the course of the church in dramatic ways’ by focusing on the depredation and destruction associated with poverty in Latin America. As Lee writes: ‘If Vatican II flowed from an updating and opening to the modern world and its challenges, the 1968 CELAM II Conference in Medellín, Colombia, specified its engagement by confronting the widespread misery in Latin America.’ Such a justice screamed to the heavens! Originally, Medellín was convoked in order to reflect upon Vatican II in relation to Latin America, but, as Lee notes, ‘its theological importance comes from the fact that it really became a reflection on Vatican II in light of the conditions of poverty and structural injustice that characterised the Latin American continent.’ This went far beyond ‘applying’ Vatican II to understand the world; rather, Lee observes: ‘Medellín took the overwhelming reality of poverty as the world’s principal ‘sign of the times’ to understand the mission of the church, a church that after Vatican II needed to be a truly global church that confronted the world’s widespread suffering.’ Vatican II expressed a generalised concern with justice, peace, and poverty, but the Medellín conference far exceeded this mission. In the words of Lee, it ‘demonstrated that although Catholics in the Global North were concerned with understanding faith in relation to the nonbeliever, for Latin Americans, the central concern was the “nonperson.”’ Latin American priests who were trained in Europe and influenced by the ‘see-judge-act’ methodology of Catholic Action – which begins by ‘seeing’ the reality in which one lives such as ‘the social, economic, and political factors that make up the daily life of believers’ – started to take seriously socioeconomic analysis, including the insights of Marxist thinkers. Such an analysis was followed by a critical turn to the Scriptures or church teaching that could lead to a new theological understanding that, in turn, would lead to action. This was a far cry from Neo-Scholasticism’s deductive approach and a recentering to include an inductive theological method. Lee writes:

Whereas Neo-Scholastic theology was deductive – that is, working from assumed abstract principles that are then applied to circumstances (if the latter are taken into account at all) – the theology and practice of liberation theology ‘were inductive, with the proclamation of the gospel, reading of the Bible, and understanding of the tenets of faith grounded in the reality of believers and their experience of God. This meant a profound, and sometimes painful, shift in understanding of personal and ecclesial identity and practice from passivity to action, from fatalism to hope.

Early proponents of liberation theology were reading the Bible with campesinos in a way, notes Lee,

that would have major consequences. In it, these farmworkers, who suffered myriad indignities and injustices at the hands of landowners, found not just individualistic, pietistic morality lessons characteristic of neo-Scholastic theology and clerically controlled Catholic pastoral practice prior to Vatican II. In addition, and more importantly, ‘they saw their own social situation illuminated by (and illuminating) these passages about a God who delivered people from slavery, prophets who denounced social injustices, and a Jesus who taught about a reign of God characterised by justice and peace.

What accounted for such a dramatic shift of perspective within the Church? Lee identified the shift as ‘the transition from the colonial fatalism that understood the status quo, and its social, political, and religious structuring, as a given order ordained by God.’ The poor and marginalised in Latin America had, according to Lee, ‘simply accepted their circumstances as God’s will and hoped for an eternal reward in the afterlife. The transformation from that mindset to one that understood God’s will in a different light came, not through political indoctrination or Marxist ideology, but through the reading of the Bible in small community settings.’ Many priests involved in pastoral work (and their opponents) would not even use the language of ‘liberation theology’ since it was deemed too controversial. According to Lee, ‘the line in the sand was the question of whether one was a “Medellín-ista” or not.’

If this sounds very much like Freire’s dialogical approach to pedagogy, that’s because Freire was invited by Gustavo Gutierrez to contribute ideas to the nascent development of liberation theology. Freire gained worldwide notoriety as a result of the success of his literacy method, which grew out of the Movement for Popular Culture in Recife that had set up ‘cultural circles’ (discussion groups with nonliterates) by the end of the 1950s. Freire believed that the oppressed could learn to read provided that reading was not imposed upon them in an authoritarian manner and that the process of reading validated their own lived experiences. Freire was not the first to recognise that adults had the capacity to speak an extraordinarily rich and complex language but lacked the graphical skills to write their ideas down. Hence, they were often alienated, imprisoned in a ‘culture of silence’ that made it difficult for them to respond to their own reality, and do so critically, dialectically. In the ‘circulo de cultura,’ Freire and his team employed codifications to engage in dialogue about the social, cultural and material conditions that impacted their lives daily. By engaging in dialogue with members of the cultural circle, the people from the local communities were able to become more critically reflective with respect to their everyday lives. Freire and his colleagues made careful notes of the expressions, the informal jargon, and the characteristic mannerisms that accompanied certain phrases to gain an understanding of the ‘cultural capital’ of the people, and these included such themes as nationalism, development, democracy and illiteracy. Sometimes these topics were introduced using slides or pictures, followed by a dialogue. The words that were chosen ‘codified’ the ways of life and the lived experiences of the local community members and permitted Freire and his team to identify generative themes from the codifications that permeated the complex experiences of learners and engage in extended dialogue with a theme to understand and analyse the concrete reality represented. This was a very different approach than learning to read from a school primer. Freire came to understand that oppressed learners had internalised profoundly negative images of themselves (images that Freire identified as created and imposed by the oppressor) and felt powerless to make changes in their lives and become active agents in history. Eventually, the group within the cultural circle examined the limits and possibilities of the existential situations that emerged from the experiences of the learners. Critical consciousness demanded a rejection of passivity and the practice of dialogue wherein learners were able to identify contradictions in their lived experience and were able to reach new levels of awareness of being an ‘object’ in a world where only ‘subjects’ have the means to determine the direction of their lives. Freire was anticlerical and opposed to the formalism and imposed neutrality of the Catholic Church, which allows the Church to pretend to serve the oppressed while supporting the power elite, which in effect empties conscientisation of its dialectical content and affirming what is essentially a static, necrophiliac (death-loving) consciousness rather than creating a biophilic (life-loving), consciousness which de facto constitutes ‘an uncritical adherence to the ruling class.’

Freire famously called for a type of class suicide in which the bourgeoisie take on a new apprenticeship of dying to their own class interests. He likened this to experiencing one’s own Easter moment through a willing transcendence. Freire believed that dominant class interests must be replaced by the interests of the suffering poor if Christians are to experience ‘death’ as an oppressed class and be born again to liberation. Otherwise, Catholics will be implicated within a Church ‘which forbids itself the Easter which it preaches.’ In this regard, Freire wrote:

I cannot permit myself to be a mere spectator. On the contrary, I must demand my place in the process of change. So, the dramatic tension between the past and the future, death and life, being and non-being, is no longer a kind of dead-end for me; I can see it for what it really is: a permanent challenge to which I must respond. And my response can be none other than my historical praxis – in other words, revolutionary praxis.

Gustavo Gutierrez, considered one of the founders of liberation theology, invited Freire to work on some components related to liberation theology, and Freire began to analyse the distinct differences between what he called the traditional church, modern church, and the prophetic church. Freire was a proponent of the prophetic church, and, in this role, he made considerable contributions to liberation theology, a movement that continues to this day and whose proponents risk their lives for the sake of the well-being of the poor, the exploited, those who were the targets of a brutal military regime. Paulo refused to exhort others to follow a path of political activism that he, himself, was unwilling to follow. His life as a metaphysical wayfarer, scholar, and advocate for poor and suffering peoples was guided by a search for justice that could only be realised through authentic dialogue. Such a dialogue stipulated engaging both politically and pedagogically the internal contradictions that plagued society. A refusal to enter such dialogue has allowed an anti-Kingdom of God to stand against immigrants seeking a better life, against migrant workers, against refugees, and the intergenerationally reproduced barrios of planet slum. Freireans today, both in Brazil and the United States, are currently under the scrutiny of political forces averse to the very concept of dialogue.

Freire is currently under attack from the fascist president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, a favourite of Donald Trump. While Freire worked as the municipal secretary of education in São Paulo at the end of the 1980s, his work was never officially integrated into Brazil’s educational system. But because Freire’s work is considered by his critics to be synonymous with the Workers Party, his writings have come under the same kinds of ideological attacks in Brazil as those marshalled against critical race theorists in the United States. That Freire was designated the official patron of Brazilian education in 2012, during the reign of the centre-left Workers Party, has been a bone of contention with the right-wing in Brazil, including conservative members of the Catholic Church. Members of Bolsonaro’s party, Partido Social Liberal, lump Freire into the same ‘social constructivist’ category as Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, whose works they claim have socially engineered a ‘cultural Marxist’ takeover of Brazilian education. Conservative Catholics continue to decry Freire’s pedagogy for undermining the traditional authority of the teacher in Catholic education. Of course, criticism of Freire is also part of the trend (all-too-familiar to American teachers, especially during the tenure of Betsy de Vos as Secretary of Education) of reducing the role of the state in education and replacing public education with private or religious schools. Bolsonaro, who has famously discriminated against women, Black people, LGBT people, Native people and quilombolas (an ancient community of escaped slaves) and immigrants and who has persecuted leftist unions and social movements, proposed that Saint Joseph of Anchieta, a Spanish-born missionary of the 16th century, replace Paulo Freire as Brazil’s official patron of education. He has described Freire’s work as ‘Marxist rubbish’ and proposed to ‘enter the Education Ministry with a flamethrower to remove Paulo Freire.’

Freire’s humanist philosophy is, for Bolsonaro, one that must be driven back into the darkness. However, the Jesuit rector and vice-rector of the National Sanctuary of Saint Joseph of Anchieta in Brazil’s south-eastern state of Espirito Santo opposed this idea on the grounds that Joseph of Anchieta was being politically manipulated by the Partido Social Liberal, and they made clear that they supported both Freire and Joseph of Anchieta who chose to fight on the side of marginalised and oppressed peoples. James Kirylo has written vitally important works on Freire and liberation theology that students of both Freire and liberation theology would do well to consider. Eduardo Campos Lima reportsthat ‘the same week of the Freire centenary, President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration was forbidden by a judge’s ruling to attack Freire’s legacy, calling the president’s various comments and institutional moves against Freire an abuse of the freedom of expression.’ Lima further notes that ‘The court decision may shut down some of Mr Bolsonaro’s semi-official campaign against Freire – there were apparently plans even to remove his statue from outside the Ministry of Education – but the war between his admirers and his critics in Brazil remains intense on social media.’ Lima writes that

[t]he divide between Freire’s critics and supporters in Brazil has implications for the church. Freire’s ideas were not only influential in the field of education but also in the Latin American liberation theology movement. A pious Christian who worked in the World Council of Churches, Freire is mentioned in several of the most relevant works of theologians like the Peruvian-born Gustavo Gutiérrez and the Brazilian-born Leonardo Boff.

Lima cites James Kirylo, an education professor at the University of South Carolina and an expert on Freire’s ideas: ‘learners explore and problematise existential happenings’ and reach through dialogue ‘critical awareness regarding the political nature of education and its intersection with the cultural, social and religious milieu.’

Lima notes how

Freire’s pedagogical ideas inspired many popular movements in Brazil, especially in rural villages and in poor communities on the outskirts of large cities. They became a central part of the Bishops’ Conference’s Movement of Base Education (known by the Portuguese abbreviation MEB), created at the beginning of the 1960s in order to teach rural and urban workers to read and write – at the same time raising awareness among them of their civil rights. At that time, illiterate people were not allowed to vote and were mostly disconnected from the political process in Brazil. Their illiteracy helped perpetuate labour exploitation and social marginalisation. Freire developed a revolutionary way of teaching literacy in 40 hours, connecting the new skills of reading and writing with a broader perception of social reality.

It is critical that we not forget the work of Catholic Action members who founded Christian social organisations that influenced the formation of the liberation theology movement in Latin America.

The controversy surrounding Liberation Theology became intensified throughout the 1970s and 1980s when it got crossways with the Catholic Church establishment for becoming aligned with rural guerrilla battalions consisting primarily of peasant workers and farmers defending themselves against rich landowners who were pushing them into poverty. After Medellin, the peasants reading the Bible with pastoral workers were doing so in a way very different from the evangelicals of the prosperity gospel (those prosperity pimp evangelists are now heard throughout Latin America, thanks in part to early funding by the CIA as one of their ways of shutting down liberation theology.) Pope John Paul II was not a supporter of liberation theology, and Ronald Reagan declared war on it. As Noam Chomsky (see Chaudary) explains, ‘the United States, not content to sit back and watch as an openly Marxist theology take hold in Latin America – a theology which threatened the US’s economic and military domination of the region – quickly moved to wipe out this emerging movement through violence.’ It did this through its strategic and logistical support of military dictatorships and its training of their death squads in the School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia. Chomsky termed these attacks on liberation theology as ‘the first religious war of the 21st century.’

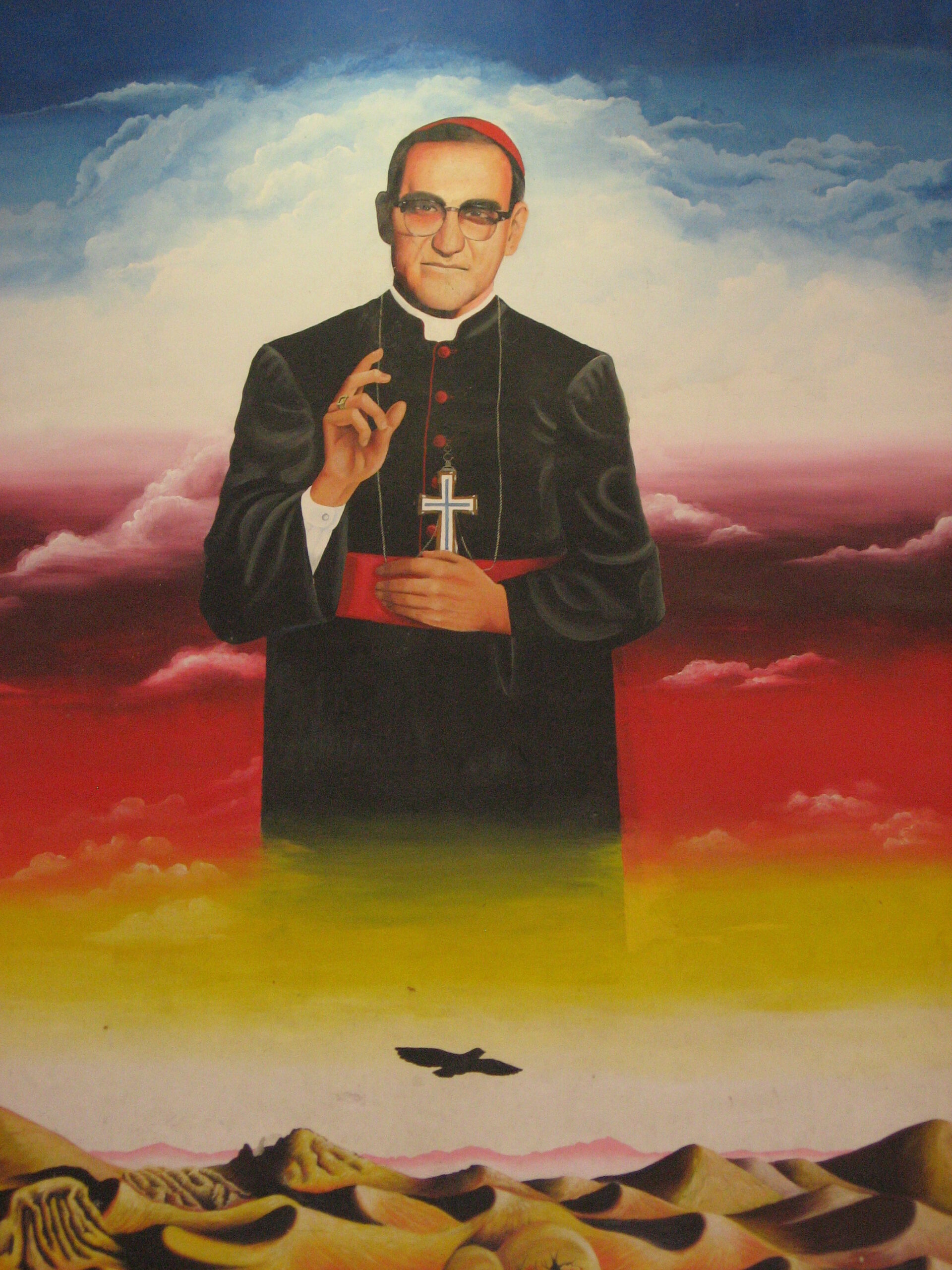

Liberation theology was so threatening to established military regimes that death threats were made against priests and nuns. Oscar Romero of El Salvador, to cite the most famous example, was threatened by the death squad known as the ‘White Warrior Union’ who threatened to kill every Jesuit priest in the country. Romero was a Salvadoran Roman Catholic archbishop who challenged in his words and acts the violence perpetrated on innocent Salvadoreans by government armed forces and right-wing death squads, who were part of El Salvador’s civil conflict. In 1980, Romero was assassinated while saying mass by an assailant from a right-wing death squad.

Despite the forces arraigned against it, Liberation Theology prevailed and became a powerful movement for social justice within the Catholic Church throughout the 1970s and 1980s, brushing against the grain of traditional Catholic catechesis. Those who gathered at Medellín were engaged in addressing the widespread suffering and injustice that marked the continent. Lee observed that

[p]art of the miracle of Medellín, and what marked it as so different from the first meeting of CELAM in Rio de Janeiro over a decade earlier, was that its attendees included representatives of different pastoral sectors and not just canonical hierarchs. The struggles, the questions, and the wisdom of working with the poor and in situations of profound inequality all had an impact on how theology would be formulated at Medellín.

This ‘correlational’ view of theology would eventually lead both to a new pastoral approach and a new and deeper understanding of faith. It was fundamentally an organic approach that avoided becoming a simple ideological imposition of Marx upon theology but rather an ‘attempt by Christians to respond to the challenging circumstances of their times and the corresponding insights into their faith that those efforts yielded.’ A foundational moment for liberation theology had come in July 1968, one month before the Medellín conference, when Gustavo Gutiérrez delivered a lecture in Chimbote, Peru, titled ‘Toward a Theology of Liberation.’ This ‘backbone’ for the new theological approach would be developed in 1971 in his landmark book, Teología de la liberación, Perspectivas. Liberation theology wasn’t essentially a monolithic approach but a diversity of approaches. Lee writes that ‘Gutiérrez’s book, like the documents of Medellín, is concerned with how the Christian good news of salvation that is the gospel is related to the cry for liberation so present across the Latin American continent, and indeed, among the majority of human beings.’

The philosophy that underlay Liberation Theology – one that combined Christianity with a Marxist critique of political economy – was first drawn up at a meeting of Latin American theologians initiated by Gustavo Gutierrez in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1964. Shortly thereafter, Christian ‘base communities’ inspired by Liberation Theology began to appear throughout Brazil, and the rest of Latin America followed, with meetings of theologians and priests held in Havana, Cuba; Bogotá, Colombia and Cuernavaca, Mexico, in June and July 1965. In 1975, Paul VI penned an apostolic exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi to the relationship between evangelisation and liberation (nos. 25-39), which addressed the desire of the oppressed to be liberated. The third general conference dealing with Liberation Theology, held at Puebla, Mexico, in 1979, revealed the theme of liberation in its final document.

Of course, today, Liberation Theology comes in many forms: Jewish Liberation Theology; Chicano Liberation Theology; Latinx Liberation Theology; Native American Liberation Theology; African American Liberation Theology, such as the magisterial work of James Cone; and feminist theologies of liberation. Liberation theologians argue that politics and religion often obtain of unwarranted and artificial distinctions. Such a proliferation of liberation theologies helps to determine when and where the hermeneutical dualism between sin and capitalist structures and relations of exploitation is to be applied, creating a more authentically Christian covenant between Catholic teachings and the poor. Base communities were constructed throughout Latin America, the goal of which was to bring laity into the Church and provide campesinos with tools to navigate the contemporary political terrain and, in doing so, strengthen their communities against state repression. Catechists (lay leaders also known as delegates of the Word) were chosen to lead the community in worship services and to promote the God of justice who proclaims the human right to take control of one’s life and refuse the bane and beguilement of intergenerational fate (for instance, a life of poverty). Liberation theologians taught that it was not God’s will that the wretched of the earth remain poor; rather, they implored the campesinos to fight for their basic human right to organise and to place their destiny in their own hands. They argued that the Church had a divine responsibility to minister to them in their struggle.

Liberation Theology gained international attention after the government assassination of six Jesuit scholars, their housekeeper and her daughter on 16 November 1989 on the campus of Universidad Centroamericana in San Salvador, El Salvador. These Jesuit priests who bucked ecclesiastic authority by supporting Liberation Theology were shot dead by soldiers because they had pushed for negotiations between the government and left-wing rebels. Those murdered included the University Rector Ignacio Ellacuria, an internationally recognised liberation theologian; Segundo Montes, Dean of the sociology department and Director of the University Institute of Human Rights; Ignacio Martın Baro, Head of the psychology department; theology professors Juan Ramon Moreno and Amando Lopez; and Joaquin Lopez y Lopez, who headed the Fe y Alegrıa network of schools for the poor. Julia Elba Ramos, wife of the caretaker at the UCA and her daughter Celina, were also killed (Ellacuria and Sobrino, 1993). Prior to these horrific murders, (the now beatified) Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero had been assassinated in 1980 while offering mass in the chapel of the Hospital of Divine Providence after famously speaking out against poverty, social injustice, and torture and urging President Jimmy Carter to stop sending helicopter gunships to the Salvadorean military. Also, in 1980, four US women, two Maryknoll nuns, an Ursuline nun and a lay volunteer were stopped by the military in El Salvador as they travelled from the airport on their way to work with impoverished campesino communities. With encouragement from their commander, a group of National Guardsmen took the women to a cow pasture where they were tortured, raped, and murdered. The rapes and assassinations of Maryknoll nuns, Sister Maura Clarke and Sister Ita Ford, Ursuline Sister Dorothy Kasel, and lay missionary Jean Donovan shocked the world. Sr Ita Ford was targeted specifically by the US-backed Salvadoran death squads because she was an outspoken critic in defence of the poor.

As a way of emphasising the point-d’appui of Oscar Romero’s theology and Romero’s shift away from an individualistic, pietistic vision of sin, Lee writes:

Any tendency to ‘spiritualise’ faith in a way that escaped or ignored the pressing of issues of his day was replaced by an engagement, a presence, or, to use the theological term that Romero himself would use, an incarnation in the world of the poor. […] His conversion of ‘seeing anew,’ which was rooted in his sense of the need for God, was tied to a profound, self-implicating realisation of social sin. Romero emphasises that the social sin of the nation is central to the conversion necessary to see God’s will be made manifest.

Lee continues:

In Romero’s view, conversion involves not simply examining individual sinful acts and repenting, but also seeing how sin is active structurally in the world and participating in ways to change those structures. Romero’s conversion widens this individualistic understanding to a social frame: he realises or becomes aware of social sin and then acts (and leads the church to act) in a way to confront that sin. Considering his neo-Scholastic theological training, he had to shift his understanding of sin from a juridical to a historical framework. That is, he moved from sin as an abstract rule-breaking to sin as the violation of God’s will for the world.

Romero himself wrote (cited in Lee):

Let me remind you what the Church teaches: that the social structures, the institutionalised sin in which we live, have to be changed. All of this has to change…. The names of the victims change, but the cause is the same. We live in a situation of inequality, of injustice, of sin; and using the force of arms, paying to kill the voice that speaks out, is no solution…. What will work is if each person in their own position – from the government, capital, labourers, landowners – strives to change things: more justice, more love.

In 2018, Oscar Romero was declared a saint at a canonisation ceremony in Saint Peter’s Square in the Vatican. During the ceremony, Francis wore ‘the blood-stained rope belt that Romero wore when he was assassinated while saying mass.’ Clearly, this was a rebuke to his predecessors, John Paul II and Benedict XVI, who believed Romero was too militantly leftist. That the Catholic Church would canonise this martyr helps me to feel more welcome in the Church, but then I realise that this murdered archbishop of San Salvador, who spoke up for the poor and oppressed, was declared a saint at the same canonisation ceremony as Pope Paul VI, who had declared birth control ‘intrinsically wrong.’ Which only points to what I feel are many of the profound contradictions in today’s Church (although I must say that Evangelii Nuntiandi. was quite an accomplishment for its time). It would take an entire essay just to list all of the apparent contradictions that plague the Church.

There are many things to despair about with regard to the Catholic Church, but the canonisation of Oscar Romero is not one of them. It is in this act that I see a glimmer of hope and possibility, especially when you contrast the spirituality of Romero and his commitment to social justice with what is happening in Ukraine under the leadership of the Kremlin’s altar boy and Chief Warmonger, Patriarch Kirill. And especially when you contrast Kirill with the person of Pope Francis, who is certainly not far enough left, but who is by far the most progressive Pope we have seen since John XXIII. And what a contrast this poses with the prosperity pastors who have pledged their allegiance to the Church of MAGA, including those who participated in the January 6 attack on the Capitol Building, crying ‘Hang Mike Pence’! You know the pastors – the ones that believe that Donald Trump is the ‘Chosen One’ – Trump, too, believes this and has told reporters himself that he is, indeed, the Chosen One and goes so far as to liken himself to the King of Israel. The belief that a man ‘who boasts about sexually assaulting married women (‘grab them by the pussy’) is actually God’s viceroy on Earth is more widely held than you might imagine, with a recent poll showing that 29% of white evangelicals and 53% of white Pentecostals hold this view.’ The same was said about Ronald Reagan, although Reagan distinguished himself as more of a ‘quasi-deity’ and not a full-fledged one in the stature of Trump. As C. J. Werleman writes:

These are the same people who believe former President Ronald Reagan to be a quasi-deity, despite him being a man who displayed an almost equal disregard for the truth, facts and intellectualism, having once claimed that trees cause more pollution than cars and praising apartheid South Africa for ending segregation at the height of the regime’s vicious discrimination against non-whites. But their slavish devotion to Trump is something altogether different – akin to the biblical story of Job, who remained loyal to Yahweh even after the Lord Almighty murdered his family and destroyed his livestock.

One good explanation for this slavish devotion to Trump as the Chosen One has been offered by Jacqueline R. Smetak, who writes: ‘Conservatives … have been using politics for the last 50 years to make their religious doctrines law. They figured out that making America what they want it to be was not to convince anybody of the righteousness of it, but to take over government at all levels.’

In 2024, Trump will perhaps ascend the throne once again, this time wrapped in a lion’s skin tunic in honour of John the Baptist, radiant as though the divine analogies that have engulfed his reputation from the night-world of big tent Southern revivalism have all been held together by the gelatin that has made his orange bouffant famous the world over. Will we be required to kneel and kiss the whip, to prostrate ourselves before this maniac perching his fleshy stretch-marked buttocks on a gold toilet he mistakes for his throne? Will Trump’s words cause the earth to rumble, rocks to split, the temple curtain to rend, graves to split open? Surely, he is the Chosen One! Will Patriarch Kirill be there, perhaps in the role of a Cherubim or Seraphim, floating about Trump’s bobbing head? Will Putin be there on his white unicorn, leading the way? Will Trump hold the bridle of a braying ass? Will he open the Gates of Heaven for all the MAGA crowd to enter in glory and triumph? After all, he is the Chosen One! Will Trump’s first act of revenge be to have the peoples of the world listen to him speak through his tiny oval mouth counterfeit syntax and the all the trivialities that flicker through his brain – person, woman, man camera – with his hands moving back and forth as if he were playing a Russian accordion? Will he bungle his chance to remake the world? God Bless America! And No Place Else!

If Trump evokes the gut-retching stench of an anti-Christ and a spectacle of the anti-Kingdom represented by a deadly cavalcade of mean-spirited, racist, homophobic and misogynistic fools, the figure of Freire brings a needed and necessary counterweight – a liberating counterhegemonic force – to the struggle for emancipation in his emphasis on pedagogy as revolutionary praxis. Freire’s impact on the development of pedagogy as a form of praxis is legendary. Praxis for Freire is never-ending; it’s a way of reinscribing people back into the world as critical agents. We are all unfinished beings whose ontological vocation is to become more fully human. This notion of unfinishedness becomes clearer as we read through Freire’s vast corpus of works, and not simply by focusing on his most famous work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. For instance, his experience of homelessness during his 16 years of exile from Brazil motivated Freire to ‘relearn’ his country upon his return. Critical pedagogy, as developed by Freire, is essentially a dynamic and recursive process in which the context of each pedagogical encounter invites new challenges and engagements that demand translation, reinvention and re-creation and thus, the process itself is continually in-the-making. You won’t find the essence of Freire’s teaching in a map or methodology. The map is not the territory, as Korzybski famously remarked. A map necessarily reduces the reality which it attempts to illuminate. And our destination is very much tied to how we choose to interpret the map (was it created by colonial cartographers? Why are the most powerful capitalist countries situated in the north? Why can’t we turn the map upside down so that Argentina is the most northern country? I wonder, does ideology have something to do with our choices?). And this is true of Freire’s contribution to critical pedagogy.

Freire’s notion of praxis refers to the bringing together of theory and practice. Praxis begins with personal agency in and on the world. We begin, in other words, with practice and then enter dialogue with others reflecting on our practice. This reflection on our practice then informs subsequent practice – and we call this process or mode of experiential learning praxis, or self-reflective purposeful behaviour, that is, exploring with others the relevance of philosophical ideas to the fault lines of everyday life and the necessity to transcend them. Freire can serve as our inspiration. But when it comes to transforming the world through our teaching, there are no clear paths to liberation, and you will only know that you have arrived once you get there. The answer won’t be found in reverse engineering Paulo Freire’s pedagogy or in retracing his steps. You must set out on your own journey. And fortunately, through our engagement with Freire’s vast corpus of teachings, he will be walking with us. To echo the title of Freire’s ‘talking’ book with legendary Appalachian educator Myles Horton, we make the road by walking, the title itself taken from the famous poem by Antonio Machado, ‘caminante, no hay camino, se hace camino al andar’ (traveller, there is no road, we make the road by walking). Freire, who travelled through numerous countries during his fifteen-year exile from Brazil (1964-1980), has been described as a type of metaphysical vagabond, a wanderer, and reminds me of the famous Zapatista saying, ‘andar preguntandos’ (walking we ask questions – a horizontal or participatory position inviting dialogue) as opposed to ‘andar predicando,’ (walking we go preaching – a ‘follow me’-oriented position). In other words, Freirean praxis is closer to resembling a ‘self-transformation of the masses approach’ than a vanguard party approach to revolutionary change – such as Lenin’s. A journalist once asked Freire how he defined himself. The answer was, ‘I am a vagabond of the obvious because I walk around the world saying obvious things, such as that education is not neutral.’ Wandering into hinterlands unexplored not only provides opportunities to err but locates making mistakes in a realm of the pedagogical encounter that provides for the possibility of growth, transcendence and emancipation.

Freire embraced humanism as the lodestar of his life’s work. He recognised that history does not make history; people make history. Freire’s work is exceptionally relevant to the future that we face. Freire recognised, as did Marx, that alienation is the signature condition brought about by capitalist exploitation. It is not a stretch to intuit that Freire was more comfortable with the Marx of the 1844 Paris manuscripts, otherwise known as the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts – written in Paris in 1844 – than with Marx’s other works promoting a communist future. Freire’s studied reluctance to more explicitly align his work with a Marxist critique of political economy and a materialist dialectics culminating in a defence of communism, and the end of prehistory was not so much a choice of forging a political detente with the bourgeoisie but rather an acute awareness of what happens to a Marxism devoid of humanism. His interest in Alvaro Vieira Pinto and the concept of ‘limit situations’ inspired Freire to develop a response to such situations with ‘limit-acts’ which constitute new ways to overcome domination. At the same time, Freire developed his own unique development of a philosophy of praxis grounded in a Marxist epistemology that was thoroughly humanist.

Much of what is attributed to the outcome of Marx’s thought – forced labour camps under Stalin, mass starvation, totalitarian ideology and organisational system – is a flagrant violation of Marx’s own work and has occluded Marx’s fundamental emphasis on the self-emancipation of human beings from social relations of exploitation, alienation and oppression – in other words, it has either ignored or rejected his emphasis on humanism. Freire was a humanist and, like Marx, was concerned about creating a society absent of the suffering experienced by so many who lived under the yolk of the capitalist mode of production. Marx’s humanism borrowed from Hegel’s philosophical humanism and emphasised the unity of theory and practice, as did Freire’s own work. Marx’s writings did not constitute a theory of everything, as in the Soviet Union’s dialectical materialism. It was a philosophical approach to understanding and transforming society rather than a scientific account of the whole of reality. Freire admired the work of Karel Kosik, whose work was not strictly Marxist but incorporated humanist phenomenology. Freire drew inspiration from a wide range of authors that included Lev Vygotsky, Karel Kosik, Eric Fromm, Antonio Gramsci, Karl Mannheim, Teilhard de Chardin, Franz Fanon, Albert Memmi and Amilcar Cabral, not to mention the dialogical humanism of Martin Buber. Freire’s work emphasised the principles of humility and love, which was influenced by the Christian Personalism of Tristian de Atiade and Emanuel Mounier.

I have used the Hebrew term ‘tikkun’ to refer to the mission of critical pedagogy. While, admittedly, the term has been overused in the past, I believe it reflects the central mission of Freire’s work and critical pedagogy in general. The term is typically translated as ‘repair the world,’ or ‘mend the world,’ and is related to the ancient Hebrew prayer known as Aleynu, in which the phrase le-taken olam be-malchut Shaddai is found and typically translated as ‘when the world shall be perfected under the reign of the Almighty.’ It can be traced back to Isaac Luria, the leading figure in the great Kabbalistic community in the Galilee, in the village of Safed in the 16th century. Luria believed the world had become shattered by human misdeeds and needed repair, and the term ‘tikkun’ has been taken up by humanitarian Jewish organisations. Thus, while the term has its roots in the mystical writings of the Lurianic kabbalah, and historically has referred to a specific cosmological account where Adam was exercised to restore God’s divine light that had been shattered and disbursed during the act of creation, it has, I believe, much contemporary relevance. Acts of repair were originally meant to imply religious acts, but I am using the concept in a more contemporary sense, and, in my use, it can be seen as synonymous with the popular concept of social justice and God as the idea of unconditional justice. By repair, I am referring to creating conditions of possibility for producing social relations of solace and hope for restive and aggrieved populations who are suffering under the forces and relations of domination and oppression. In one immediate sense we can think of repairing the world that has been shattered by the singular evil of certain men – I am thinking here of Reinhard Heydrich, one of the most evil men in history, who was as intimately connected to the execution yards as to opulent palaces and high culture that overlapped with his ferocious quest for power and burning sense of mission, namely, his investment in the extermination of the Jews and the Germanisation of Europe. But I am also referring to the concept of ‘mipnei tikkun ha-olam,’ which in the ancient Mishna refers to public policy initiatives designed to protect the vulnerable and the dispossessed. Here we can examine the efficacy of the term ‘social sin,’ which refers to the structural manifestations of power and, in my own Catholic tradition, refers to institutionalised and systemic racism, misogyny, white supremacy, homophobia, antisemitism, and the systematic exploitation attached to capitalist social relations of production – not to mention ecocide, genocide and epistemicide (the destruction of the cosmovisions and history of indigenous peoples). I found the idea of healing and repairing the world created by ‘social sin’ useful in my approach to critical pedagogy, which is grounded in Latin American Catholic expressions of liberation theology.

So, Mr Trump, you can prepare yourself for a cultural battle. Start firing up your quislings and sycophants. Yolk together with your lies and racist assaults on immigrants, your illiberal MAGA conscripts who find perverse comfort in erecting gallows outside the Capitol Building and calling for the execution of the Vice President, who brandish a vision of a ‘Christian’ America as a land of white Stetson-wearing gunslingers who ‘stand their ground’ and are entitled to a decent burial in Boot Hill, a vision where the government exercises complete control over women’s bodies, discriminates against LGTBQ communities, and builds a wall to protect fragile white people from the taint of difference. Issue your call to arms for those who wish to preserve ‘our way of life’ (meaning the lives of white people) by refusing to allow students to learn about the racist history of their country and by supporting a system that rewards the rich and demonises the poor. Do as thou wilt, Mr Trump, and we will offer you a vision of a counterpublic sphere built on redefining the foundations of freedom and justice for all and challenging those whose interests they serve. Such a redefinition will consider the tenets of liberation theology and the examples of Oscar Romero and Paulo Freire and many others whom we have met along the winding road to justice, a road pockmarked with craters from switchblade drones, a road that has been mined by hate and blocked by the rubble from Parisian cobblestones over the centuries and which you are now attempting to remove from the map of history.

Note: Sections of this essay have been reworked from my contribution on liberation theology to Masuria, A. (Ed.). (2022). The encyclopaedia of Marxism & education. Brill.