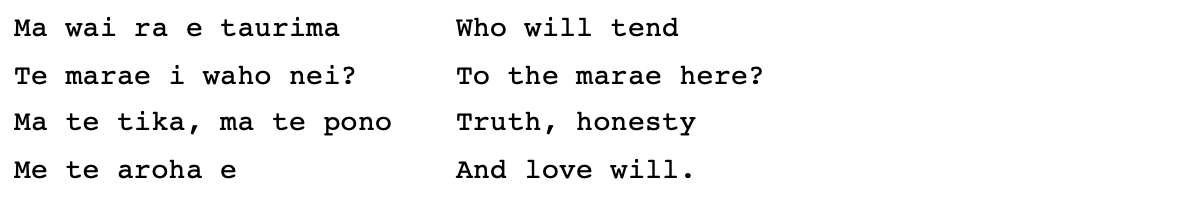

Ma wai ra (Henare Te Owai, Ngāti Porou) [follow the link for the words of the waiata and to hear a rendition]

What is the deeper significance of adopting aroha as a university value, beyond the sunlit realm of kindness and compassion towards one another in our workplaces? I am asking this question in seeking to extrapolate from my recent article, written with four Māori friends, about the adoption by AUT (our employer university) of three key Māori ethical principles, tika, pono and aroha, as its university values. That article was critical of their treatment by AUT because

- these three large Māori concepts are treated as if distinct from each other,

- each of the three Māori concepts is translated by only one English word, and

- poor choices of English words have been used to represent the meanings of each Māori concept.

My co-authors and I called for the restoration to these values of their full meanings in Māori terms and declared a rhetorical rahui (ban or restriction) over them as AUT values, pending further discussions within the AUT community. In this column, I extend those discussions by focusing in depth on the Māori concept of aroha and its value in the contemporary university context.

The notion of ‘university values’ has become popular in recent decades as each university has been obliged to develop its institutional identity as a ‘brand’ in the academic market, the creation of which was catalysed by neoliberal influences on education policy. Reflecting this trend, some years ago, certain esteemed Māori elders gave their collective blessing for AUT to adopt as their university values the three central values of Māori philosophy: pono (truth), tika (justice) and aroha (love). On the AUT website, each of these three profound Māori concepts is represented by only one English word, with aroha interpreted as compassion. But this treatment is reductionist because just as love means much more than compassion, so does aroha, according to the academic literature we consulted to write our article, especially those sources written by earlier generations of Māori scholars. A longer English definition of a big idea such as aroha is more useful, as in the following paragraphs …

Aroha is the closest Māori equivalent for love, but the two concepts do not completely match in meaning. Not all of the nuances of love apply to aroha, while aroha has layers of meaning that are conveyed in English by words other than love, such as sympathy, compassion, nostalgia, open-mindedness, generosity, etc. The word aroha can be broken into aro + hā: aro is a verb that means to pay attention, while hā means the breath. Aroha, therefore, literally means to follow the breath, which implies attentive care for self and other: to follow one’s heart; to go with the flow.

Inherent in the concept of aroha is a ‘deep comprehension of another’s point of view’ and an ‘unconditional concern and responsibility for others.’ Thus aroha calls to a larger concept of love, understood as a boundless sense of responsibility for each other – whomever it is with whom we interact. Responsibility and responsiveness are linked, both part of a concept of aroha that derives from a Māori worldview. Responsibility to others in relationship sits at the heart of a Māori ethics based on indigenous concepts of whakapapa, mana and manaaki. Māori politics based on these traditional concepts is a fundamentally relational politics: one which recognises the risk of relating and relates anyway. Such a relationship is an ‘enabling binary’ that is the complete opposite of the binary of terrorism, in which ‘neither side can really “see” the other.’ The concept of aroha, understood as an infinite sense of responsibility for the other with whom we are in relationship, is a flexible and aspirational ethical principle.

Māori elder-scholars who have written about aroha include Cleve Barlow, Māori Marsden, Hirini Mead, Henare Tate and others. These elders describe the full meaning of the three basic Māori values of tika, pono and aroha. In these writings, aroha is described as a ‘supreme power’ overarching both pono (truth) and tika (justice). Aroha is key to what makes us human. To translate aroha simply as ‘compassion’ is therefore inadequate and misleading. If we are taking Māori knowledge seriously, such simplistic treatment transgresses the truth criteria on which rest AUT’s claim to be a university. This argument cuts straight to the heart of the university and demonstrates why this topic is significant to the university’s claims about being committed to Māori interests.

In adopting these three Māori concepts as its university values, AUT could reasonably have expected to be recognised as innovative and ‘Treaty-led’ in reference to (te Tiriti o Waitangi) the Treaty of Waitangi 1840. This treaty between the British Crown and the rangatira (tribal leaders) is recognised as the founding document of the national identity of Aotearoa New Zealand and underpins its claims to biculturalism and the best race relations in the world. But the chain of reasoning from tika, pono, aroha to Te Tiriti o Waitangi is obscure. To translate aroha as ‘compassion’ is philosophically truncated and reductionist, but to translate aroha as the larger English concept of ‘love’ would introduce many large new problems, given the range of thoughts and actions included under this one little word, love, some of which are simply outside the scope of the legitimate business of a university such as AUT.

The reductionist treatment of the concept of aroha prevents consideration of its other meanings besides compassion that are equally relevant, if not more so, for the core business of a university. While acknowledging that we must always act with kindness and compassion, I argue that the meanings of aroha, in combination with tika and pono, also include critique – and that this shade of meaning is extremely important and topical for the consideration of guiding values at AUT. I first made this argument in reply to the infamous Listener letter of 2021, in which seven senior professors wrote ‘in defence’ of science, which they said was under attack from Mātauranga Māori, or its champions. In responding, I referred to my love of nature leading me to love science, which studies nature. To critique science according to these lights is an act of aroha, similar perhaps to ideas of ‘tough love’ or ‘constructive critique,’ motivated by a wish for science to be better. Only when science is at its best, only when it adheres to its own criteria, can it give humans its best version of reality. Scientists today seem unaware that, for 200 years, science has been subservient to motivations of war and profit. The antipathy many scientists express in response to any suggestions (including mine) that science played (or was given) a role in justifying the colonisation of Indigenous peoples, including Māori in Aotearoa, is as puzzling as it is vitriolic. Surely, I would have thought, the principles of science should invite and welcome a process of ongoing critique of itself?

Scientists are showing up their innocence in philosophical terms in their uninformed attacks on Māori knowledge and scholars. By not understanding what they perceive as their enemy, they are allowing themselves to fall prey to trends (imported from post-Trump USA) of vilifying all critical theory. Scientists are acting from fear, not aroha, when they ridicule Māori knowledge on flimsy grounds and with little or no professional expertise behind their claims, and I am being sent more and more examples of such knee-jerk responses. When scientists accuse scholars of Māori knowledge, including me, of wanting to ‘subvert’ and displace science, all I can do is respond with aroha. Aroha is connected to tika and pono, so includes a sense of respect and love for truth and right action. Universities are places in which these attitudes are needed, now as much as ever before.