Ye, therefore, beloved, seeing ye know these things before, beware lest ye also, being led away with the error of the wicked, fall from your own steadfastness. (2 Peter 3:17)

By now, much of the world has recoiled at the influx of images portraying screaming insurrectionists smashing their way into Brazil’s main government complex in what constitutes a massive challenge to human rights protection, the rule of law, and the security of democratic institutions. It also brings to the forefront the obstacles for confronting the disinformation and hate campaigns exercised by repressive regimes such as Bolsonaro’s, who are vying to propagate digital platforms through a sovereign nationalist technological infrastructure. Such an infrastructure is designed as an ideological weapon of death intended to cement a propaganda regime that harkens back to Brazil’s brutal military dictatorship so loved by Bolsonaro. Jake Johnson reports that this attempt to overthrow Brazil’s newly elected government was ‘directly aided’ by major social media platforms such as Facebook, TikTok, and Telegram, according to the global watchdog group SumOfUs. Brutal online practices such as these are mutating in rhizomatic fury across continents and spreading their seditious ideological filth throughout much of the world. Supporters of far-right former President Jair Bolsonaro utilised the platforms, tools, and algorithms of major media giants in order to agitate for fascism before fleeing to the home of a mixed martial arts ex-champion in Florida.

Johnson informs us that Rebello Arduini, campaign director at SumOfUs, a nonprofit that has been monitoring the proliferation of election lies on Brazil’s social media, has likened the brazen assault on Brazil’s democracy to the January 6, 2021 assault on the US Capitol, ‘which was also abetted by social media giants.’ This is not so surprising since Trump was a major supporter of Bolsonaro. In the midst of such a digital architecture of devilish repression, we face the prospect of new technologies being used in the service of autocratic fantasies of domination. In fact, such fantasies are being playing out right before our eyes, and they are becoming lessons for our students. While QAnon conspiracy theorists claim Democrats are paedophile cannibals and drink the blood of children, under the snickering gaze of Lucifer, Bolsonaro actually bragged that he would enjoy cannibalising an Indian while describing a trip to the Yanomami people. Bolsonaro is nostalgic for the 1964–1985 military regime that murdered and tortured thousands of leftists. He has been accused of ‘drinking from the sewer of history’ after a video showed him urging teenage students to read the book, The Suffocated Truth – The Story the Left Doesn’t Want Brazil to Know, by Col. Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, an infamous account written by a notorious dictatorship-era torturer who orchestrated interrogation sessions ‘where victims were whipped, given electric shocks and pounded with vine wood canes.’

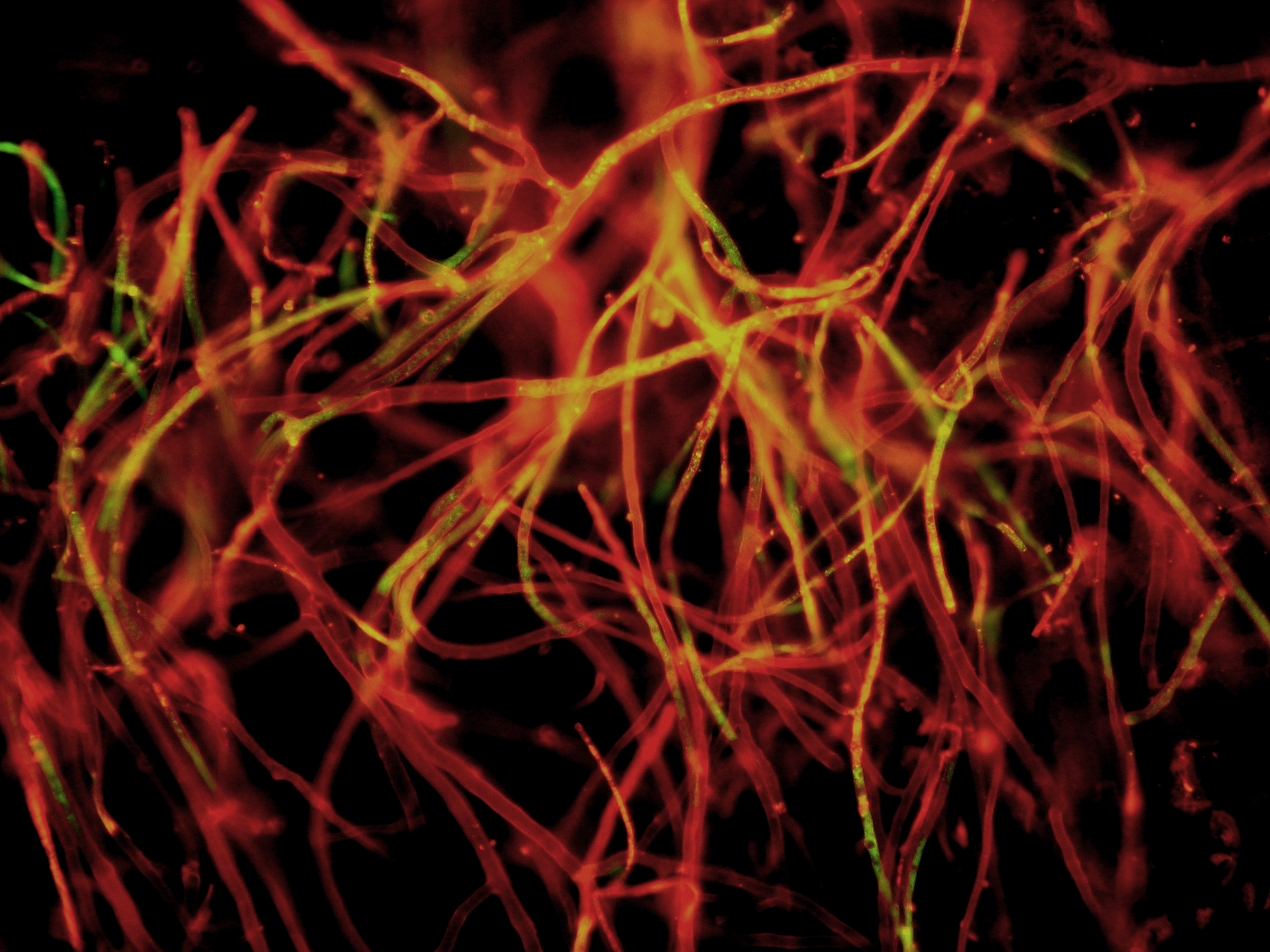

Arduini exclaimed, reports Johnson, that ‘we’ve now seen this happen in two of the world’s major democracies – if governments fail to respond, more will inevitably pay the price.’ Johnson notes that SumOfUs issued a report on the eve of Brazil’s presidential runoff, detailing how TikTok and Meta – the parent company of Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp – were putting the ‘integrity of the election on the line through their disastrous recommendation systems.’ It’s one thing to be shocked by learning how far-right extremists are operating freely on Meta’s platforms in Brazil by calibrating their algorithms so as to prioritise anti-democratic groups. It is another to recognise that the same things are happening in the US and other countries, where digital connective tissue is growing that supports, protects, and gives structure to larger organs of hate as part of a living, electronically pulsating body of which Dr Frankenstein could only dream.

To employ another discursive analogue, this digital connective tissue can be likened to mushroom intelligence, the symbiotic relationship between fungi and plants, with ‘mycelium’ creating a ‘mycorrhizal network,’ which connects individual plants together to transfer water, nitrogen, carbon and other minerals. Under our very feet, rhythmic electrical impulses are transmitted across the mycelium of four different species of fungi, creating a fungi language of about 50 words that can be organised as sentences. Before accusing me of designating this vast underground intelligence system as the ‘root metaphor’ for the deep state operating in the ‘wood wide net,’ I wish only to say that I am trying to emphasise the capacity of our post-digital universe to create transnational mobilisations across various countries, groom groups of youth for the kind of hate that could serve as a precondition for the growth of fascist and neo-Nazi ideology – all of which is catastrophic for humanity’s quest for democracy. According to Johnson, ‘SumOfUs estimated that Facebook ads sowing doubt about the Brazilian election and agitating for a military coup accumulated at least 615,000 impressions.’ Johnson summarises the seriousness of the situation and is worth quoting at length as follows:

But critics say Meta and other major social media companies ignored or brushed off warnings that their platforms were being used as crucial organising hubs for the insurrection. The Washington Post reported Monday that ‘in the weeks leading up to Sunday’s violent attacks on Brazil’s Congress and other government buildings, the country’s social media channels surged with calls to attack gas stations, refineries, and other infrastructure, as well as for people to come to a ‘war cry party’ in the capital, according to Brazilian social media researchers.’ Pointing to SumOfUs’s research, the Post noted that ‘Facebook and Instagram directed thousands of users who plugged in basic search terms about the election toward groups questioning the integrity of the vote.’ The newspaper added that ‘researchers in Brazil said Twitter, in particular, was a place to watch because it is heavily used by a circle of right-wing influencers – Bolsonaro allies who continue to promote election fraud narratives.’ ‘Billionaire Elon Musk, who completed his acquisition of Twitter in late October, fired the company’s entire staff in Brazil except for a few salespeople,’ the Post reported. ‘Among those fired in early November included eight people, based in São Paulo, who moderated content on the platform to catch posts that broke its rules against incitement to violence and misinformation.’

To what extent have we vacated our own power by our use of the internet in the mundane activities of our quotidian digital life? To what extent has our daily saturation in digitality sidestepped our trust in moderators of social media platforms and, unbeknownst to us at first, threatened the health of the politics that define our built environment through cultural shifts for which we are responsible?

Eva Frederick reports on a new study that ‘treats online hate as a living, evolving organism and tracks its spread and interactions over time.’ The research team is led by physicist and complexity researcher Neil Johnson of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., who has fashioned mathematical models to analyse data from social platforms including Facebook and the Russian social network Vkontakte (VK). What is important about these platforms is that ‘users can form groups with others of similar views.’ That is because the research seeks to explore online hate ecosystems and, in the words of Ana-Maria Bliuc, understand ‘how online platforms help ‘haters’ unify across platforms and create ‘hate bridges’ across nations and cultures.’ The researchers found this ecosystem of hate to be ‘like a continuous spectrum, where many kinds of hostility bleed into one other – a ‘superconnected flytrap’ that pulls people further into a broad, ever-changing online hate community.’ Frederick writes that ‘[t]he researchers mapped interactions between related groups, primarily by tracking posts that linked to other groups. Their breakthrough came when they realised they had to track these interactions across social platforms. Instead of hate groups gathering in a single place, they often meet on many different networks – and tighter restrictions on one platform simply cause hate communities on other platforms to strengthen. Cross-platform linkages are referred to as ‘hate highways’ and ‘form especially quickly when a group feels threatened or watched.’ Here is one example provided by the researchers:

In the aftermath of the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, for example, many media outlets discussed the shooter’s interest in the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). In turn, online KKK groups likely felt increased scrutiny, Johnson says. He and his colleagues found a spike of posts in KKK Facebook groups linking to hate groups on different platforms, such as Gab or VK, strengthening the ‘decentralised KKK ideological organism.’ Hate highways can be powerful in uniting people across geographic boundaries, Johnson says: ‘With one link between 10,000 Neo-Nazis in the U.K. and 10,000 Neo-Nazis in New Zealand, and then another with 10,000 in the US, suddenly, within two hops, you’ve connected 30,000 people with the same brand of hate.’

Johnson describes the KKK as an ‘ideological organism.’ When a hate group on one platform is banned, other platforms can serve as incubators, such as in the case of Facebook’s crackdown on KKK groups in 2016 and 2017. In that situation, many of their former members fled to VK, a social media platform popular in Russia and Eastern Europe. Frederick reports that with VK, they found a virtual ‘welcoming committee,’ with entry pages directing them to other hate communities.

The researchers discovered that banning particularly active and hateful groups is ineffective and recommend other approaches such as ‘quietly removing small groups from the platform, while leaving larger ones in place. Because small groups eventually grow into larger ones, this policy nips them in the bud. The second policy is to randomly ban a small subset of users. Such a ban, Johnson says, would be less likely to enrage a large group, and he proposes it would also decrease the likelihood of multiple lawsuits.’ Other policy options are more controversial, including ‘creating antihate groups that would attempt to engage with the hate communities, in theory keeping them too preoccupied to actively recruit. The last would introduce fake users and groups to sow dissent among the hate groups.’

Other issues that need to be debated have to do with government policies to tighten control over technology companies and requiring platforms to align their content moderation and recommendation systems with pro-government policies, the problem of the global police state and global civil war emerging as a result of the digital transformations linked to capitalist social relations of exploitation and domination which are related, as William I. Robinson eruditely points out, to the structural crisis of capitalism and the political crisis of social reproduction, of state legitimacy, of capitalist hegemony, of the social fabric, of the crackup of political systems around the world. It’s a crisis of over-accumulation with no profitable reinvestment opportunities for the wealthy, of fictitious capital, or of unprecedented amounts of predatory finance capital that Robinson argues is destabilising the system, of the precarisation of labour, the massive amount of surplus humanity, the attacks on working and popular classes. Surplus capital means surplus people, after all, and the threat of nuclear war. The transnational capitalist class are looking to new digital technologies to create a new round of expansion and prosperity, which will lead to a new social contract with workers that basically amounts to little more than slavery where 80% or more of humanity can’t consume with the inequality that exists. Robinson has published a book, The Global Police State, which addresses what he calls ‘militarised accumulation,’ that is, expanded systems of warfare where border walls are erected for refugee control, and mass systems of mass incarceration and systems of state surveillance and surveillance and tracking are created. This is immensely profitable for the war industrialists, who, in the face of economic stagnation, help keep the economy going through social control, cyber warfare, and conflict. It is worth pondering what Robinson has said about the recent COVID-19 pandemic:

‘The 10 richest men doubled their fortunes in the pandemic, while the income of 99% of humanity fell during the pandemic. A new billionaire is minted every 26 hours as inequality contributes to the death of one person every four seconds.’ And then this report says the world’s 10 richest men more than doubled their fortunes from $700 billion to $1.5 trillion at a rate of $15,000 per second, or $1.3 billion a day during the first two years of the pandemic that has seen the income of 99% of humanity fall and over 160 million more people forced into extreme poverty. ‘If these 10 men were to lose 99.999% of their wealth tomorrow, they would still be richer than 99% of all the people on this planet,’ said the report. They now have six times more wealth than the poorest 3.1 billion people.

Steven Feldstein reports on authoritarian governments that are on the offensive in deploying digital tools to monitor, track and control their citizens. He defines digital repression as ‘the use of information and communications technology to surveil, coerce, or manipulate individuals or groups in order to deter specific activities or beliefs that challenge the state’ and organises this concept into five categories of overlapping techniques: surveillance, censorship, social manipulation and disinformation, internet shutdowns, and targeted persecution of online users. He writes in his book, The Rise of Digital Repression: How Technology is Reshaping Power, Politics and Resistance, that an ‘important insight about digital repression is that it operates in a larger ecosystem of political repression; my research shows that a government’s curtailment of political civil liberties – censoring political speech, preventing groups from organising, restricting academic freedom or banning political parties – is causally related to the deployment of digital repression.’

Feldstein further observes that

many weak or fragile democracies also deploy digital repression strategies. Countries such as India, Brazil, Turkey, the Philippines (profiled in my book), Nigeria, Serbia and Hungary are responsible for deploying an array of techniques, from internet shutdowns (India leads the world in shutdowns), social media disinformation (Philippines’ President Rodrigo Duterte has staked his rule on his ability to systematically distort online information), to social media censorship (Nigeria recently banned Twitter use in the country; Turkey has instituted a new social media law with burdensome content removal and localisation requirements). Generally, democracies favour using information manipulation tactics – such as disinformation campaigns – over more heavy-handed approaches, like mass surveillance or widespread censorship filtering of websites. But the notion that democracies do not rely on digital repression tactics simply is not true.

Fortunately, this description doesn’t leave the US off the hook. The struggles over digital technological innovation will, for the foreseeable future, remain a contest between autocratic governments and their civic constituencies. Describing technology as existing ‘in a constant state of iteration and advancement,’ Feldstein estimates ‘that the cycle of technological innovation will continue to power a global cat-and-mouse struggle between autocrats who seek to exploit communication technologies for political gain, and civic and opposition members who will leverage the same tools against these regimes.’ In order to combat America’s ‘addiction to collective denial and selective ignorance when it comes to the nation’s history,’ Aastha Uprety and Danyelle Solomon advocate a progressive digital agenda designed to mitigate this current incarnation of hate and violence. They argue that ‘[w]ithout proper oversight, regulation, and accountability to combat the ugliest online realms, society will never reap the full benefits of the digital world.’ Uprety and Solomon urge an expansion of enforcement mechanisms that should ‘involve employing artificial intelligence, user flags, and well-trained human content reviewers to help to identify and remove hateful content.’ In doing so, ‘[c]ompanies should disclose the methods through which reviewers determine which content to remove and if a user’s actions warrant suspension or termination. In addition, companies should regularly release data on how many users have been denied services, why the users were removed, how many appealed, and how many appealed successfully.’

What the authors address particularly well is their accounting of explicit discrimination against racial minorities, particularly through the use of algorithms used to design social media platforms and search engines. Algorithms are ‘the functions used by computer programs to make automated decisions,’ and, as the authors point out, they can ‘reflect both the biases of their human programmers as well as the biases in the data these algorithms use to make decisions.’ Many of these algorithms produce racially biased outputs on online platforms enabling companies to discriminate – intentionally and unintentionally – ’against users of colour or promote propaganda that reinforces false narratives, and that plays to negative stereotypes.’ This is not only wrong from an ethical perspective; algorithmic bias also damages the economy by excluding consumers and validates extremist views. These online platforms ‘drive content to a user by relying on algorithmic predictions of what the user wants to see based on prior interests, which can sometimes result in intentional or inadvertent discrimination.’ How does this work? The authors provide some examples that are worth quoting at length:

Targeted ads for credit cards, for example, raise questions about who could be on the receiving end of predatory marketing, especially if race is a distinguishing factor. Some vendors will price discriminate or offer different prices to different potential consumers based on an internet user’s ZIP code. While common, this practice can result in racial discrimination by geography. Google posted ads for criminal background checks, as well as credit cards with exorbitant fees and high interest rates on an African American fraternity’s website. Recently, Facebook has also come under fire for allowing advertisers to target specific audiences by categories, including ‘Ethnic Affinity,’ which enabled sellers to basically racially discriminate by excluding users associated with certain characteristics from seeing their ad. For example, sellers could exclude user traits such as ‘African Americans’ and ‘Spanish speakers’ from their target audience. After this practice was uncovered, the National Fair Housing Alliance sued Facebook, claiming that the social media company was violating the Fair Housing Act. Online platforms such as Facebook should commit to updating the algorithms and guidelines used to detect whether an ad is discriminatory. Facebook should be able to catch and prevent not only blatant discrimination–such as preventing a user whose interests include the topic ‘African American’ from seeing a specific ad – but also more discrete discrimination, such as housing redlining via limiting audiences to certain ZIP codes. Search engine algorithms can also reflect racial bias. One study found that entering black-identifying names into Google displayed ads suggestive of the person having an arrest record, a phenomenon that did not occur as frequently for white-identifying names. For example, a search for the first names ‘Latanya’ and ‘Latisha’ displayed ads for a background check service, but a search of the names ‘Kristen’ and ‘Jill’ rendered neutral results.

What kind of regulatory action and policymaking do we need? I feel somewhat at a disadvantage in answering my own question since I wrote the first draft of my dissertation on an IBM Select typewriter in 1982 and my final draft on a Wang word processor. In 1928, my great aunt, Irma Wright, won the world’s amateur typing contest at 116 words per minute on an old manual typewriter. She had been a diamond medallist and five times Canadian professional champion. She had won the Canadian Open and the Quebec Bilingual crowns for 1924. She used to practice by typing the novel, Gone with the Wind. She was known as Canada’s ‘Blue Eyed Mistress of the Keys’ and was considered one of Canada’s first feminists for advising budding secretaries not to reply to advertisements for ‘Girl Friday’ or ‘Office Wife.’

While I enjoyed the typed letters I received from Aunt Irma, I never became much of a typist and fumbled around with technological innovations, and, for the longest time, resisted e-mail. To this day, I am nostalgic for the days prior to the computer revolution. But I am not a Luddite. Yet I worry how the typewriter evolved to provide a more potent mechanism of attraction for both Mr Rogers and Joseph Goebbels, as it made its way ‘from a glorified typewriter and game console to an indispensable telecommunications portal.’ The quantum internet beckons, and the quantum computer is next in line. Through entanglement, a strange quantum mechanical property once derided by Albert Einstein as a ‘spooky distant effect,’ researchers aim to create intimate, instantaneous links across long distances. A quantum internet could weld telescopes into arrays with ultrahigh resolution, precisely synchronise clocks, yield hypersecure communication networks for finance and elections, and make it possible to do quantum computing from anywhere. It could also lead to applications nobody’s yet dreamed of.’ Yes, it’s those applications that bother me. What will be the outcome when thousands upon thousands of disaffected MAGA minions become entangled with Hitler’s digital brain? What will happen when disaffected suburban youth are quantum mechanically ‘entangled,’ linked like identical twins to psychopathic libertarians who know each other’s thoughts despite living in distant countries?

We need a post-digital pedagogy that can help us develop democratic policies and practices for our post-digital world, including the geopolitical dimensions of that world. Petar Jandrić has been instrumental in creating spaces of inquiry and development directed at the post-digital revolution. Those adhering to Henry Giroux’s courageous call for the creation of a democratic public sphere, and the ethical imperatives that drive Michael Peters’ concept of ‘ethos of community,’ would do well to follow Benjamin Green’s recommendations when it comes to the challenges of digital technology. With respect to developing measures of resistance to the online vitriol of extreme speech, Green advocates an education founded on a critical social ontology, a community fostered around ethical critique that provides ‘a framework for a system of postdigital collective education.’ He describes such as system as in possession of ‘the means of establishing what Jandrić calls the postdigital trialectic of collective intelligence, i.e., ‘we think,’ ‘we learn’ and ‘we act.’ For Green,

this trialectic represents a coalition of praxis based in co-constructed knowledge and methodologies aimed at overcoming the inherent challenges to a postdigital society marked by social division, multiple discourses and impaired democracy…. Thusly, by instilling young people with the ability to critique a form of modernity rooted in a deontological knowledge economy based in individualistic rationality, e.g., post-truth populist narratives of xenophobic patriotism/nationalism – an ethos of community lays the foundation for a postdigital critical social ontology. This critical social ontology provides a sustainable means by which our current postdigital global risk society may engender an open system of education based in self-reflexive democratic collective intelligence.

We need to resist the creation of today’s fascist global village. It is not enough to recognise (and recoil at) how the aggregation of fascist prerogatives through the intersectionality and intermediation of platforms run by ideologues, clickbait operators and influencers for hire working for gangster capitalists paid for by members of Washington’s Chaos Caucus are contributing to this reality.

We need more than trusted flaggers, digital trainers, independent auditors and AI-assisted content moderation as countertactics. We need a critical pedagogy and a philosophy of praxis that can create a world dominated by spaces of collaboration whose members actively participate in grassroots anti-racist and antihate communities absent of the alienation that results from the virus of capitalist value production. We need cultural workers, exemplified by Henry Giroux and others, who view pedagogy not as a career but as a way of life.