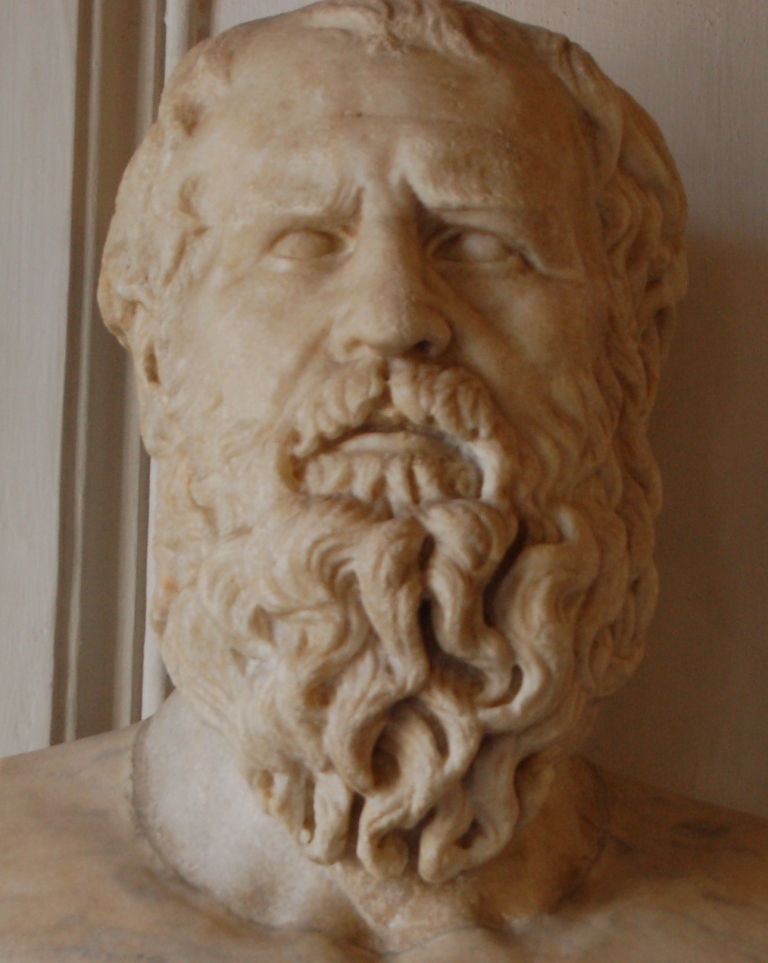

Heraclitus, or Herakleitos (c. 500BC), famously addressed the classic Greek philosophical problem of reality (in part), saying, ‘You cannot step twice into the same river.’ It is not only the river that is constantly changing, but you also. Heraclitus’s resolution of the problem of identity (same/different) and related philosophical problems (appearance/reality) was presented not as an authoritative genius but as ‘Having harkened not to me but to the Word (logos), it is wise to agree that all things are one’ (B50).

In this, Heraclitus suggests there is a universal rational order of things to which he seeks to draw attention. Thus, the ‘Word’ is not a linguistic entity but the independent way the world is. This is similar to John 1.1: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.’ Each presupposes the speaker has privileged access to the Logos such that what they say is true. The privileged access enables the speaker to see behind the temporal appearance to the foundational eternal reality. Because what they say is true, the audience is entitled to believe and act on what they say. One of the controversial consequences drawn from Heraclitus’s account is that contradictories are both true. An important difference between Heraclitus and most others influenced by Greek philosophy is that Heraclitus saw change, whereas others saw permanence.

What difference would it make if the Word (logos) is taken to be a linguistic entity and change from one relatively stable condition to another is the way of the world? That is, if there is no privileged access to a foundational reality, how do we actually best deal with appearance? If change (whether incremental or cataclysmic) is the way of the world, how do we understand conditional permanence? How would such a way of seeing the world and acting in it change the use of ‘true,’ or would it be better to emphasise ‘trust’ as the default basis for belief, knowledge and action? Ludwig Wittgenstein warns

Here, we are in enormous danger of wanting to make fine distinctions. It is similar when one tries to explain the concept of a physical object in terms of ‘what is really seen.’ Rather, the everyday language-game is to be accepted, and false accounts of it characterised as false. The primitive language-game which children are instructed in needs no justification; attempts at justification need to be rejected. (Philosophical Investigations, p. 210e)

A language game is a linguistic entity, but it is more than words. It is an evolving practice that uses and is shaped by words, purposes, standards, procedures, actions and consequences. It is the way we deal with energy manifesting itself according to the laws of physics and chemistry. This energy limits but does not determine what we see and do. Within those limits, what we see and do is as a consequence of our engaging with the world in the context of an evolving language game/practice/tradition. Traditions evolve in response both to the changing energy patterns and to the dynamics of the operation of the tradition as practitioners seek to optimise the outcomes of their actions.

The conditional account of knowledge of the world requires belief, evidence, truth. A foundational account of truth requires privileged access to reality such that a true statement corresponds to reality and is infallible. This privileged access is what justifies the claim of truth. Without such access, claims to truth are based on appearance and are more or less fallible but may seek to pretend to be infallible. Israel Scheffler, in Conditions of Knowledge, considered a ‘weak’ conditional account of knowledge as justified belief. This lacks a sense of commitment implied in a knowledge claim that ‘true’ provides. An account of knowledge as belief, evidence, trust provides a stronger commitment than ‘true.’ Trust in a knowledge claim is a commitment by the practitioner rather than an independent condition of the world. Both trust and truth are subject to revision in light of changing conditions.

Recognition of trust as an integral part of the operation of evolving traditions in society and the knowledge claims made within it could improve the education process in schools.