Doug Goldson

High School Teacher, Queensland, Australia

Abstract

The teaching profession in Australia is in crisis. There is a dramatic shortage of teachers and little prospect of significant improvement in the years ahead. This commentary gives an insider view of what is wrong with the teaching profession. The crisis is a complex problem with complex causes. This view is necessarily partial, with a focus on Queensland, and on teacher workload as a cause of the workforce crisis.

Keywords

Teacher workforce crisis; workload

Why is school teaching such an unappealing profession? It is a dismal question that makes it important at the outset to differentiate lack of appeal and lack of worth. Few deny that education is an intrinsic good. So why is the profession so unappealing? Given the disposition to not see what is not welcome, the temptation to downplay the teacher crisis is countered by a cursory search of news media. Searching for ‘teacher shortage’ on the Australian news service, ABC News online, turns up 40 articles in the 14 months from June 2022 to August 2023. While Australia is the focus of this article, with a specific focus on Queensland, it is clear that the teacher crisis extends far beyond Australia. Searching for ‘teacher shortage UK’ on the Guardian news service turns up 15 articles in the 13 months from June 2022 to July 2023. The following excerpts illustrate the severity of the Australian problem:

Queensland and New South Wales will … each [need] more than 1,700 teachers by 2025.

(Hinchliffe & Rose, 2022)

Demand for secondary school teachers will outstrip graduates by more than 4,000 in coming years. (Convery, 2022).

This article gives an insider view of what is wrong with the teaching profession. Since the crisis is a complex problem with complex causes, it is important to qualify this insider view by pointing out some ‘weaknesses’. The analysis is partial in several respects. The focus is on teacher workload as a cause of the workforce crisis, but this is not the only cause of it. The focus is on top-down policy-making, detached from practical workplace realities, as a cause of excessive work, but this is not the only cause of it. Overwork is manifest in many different ways. Lastly, the analysis is bottom up. It is based on several implied generalisations: from the relevance of my experience to others I work with; from my high school to other high schools; from high schools to primary; from metropolitan to rural schools; from Queensland to other states; and so on. To the question: ‘Apart from what you say, where is your evidence?’, I reply that, if this analysis is a basis for action, it is to ask teachers across the State if it is a useful step towards collective action.

From a different, and somewhat paradoxical, point of view, the limits of this analysis are its strength. One cause of the teacher crisis is the ideology of decision makers, the bureaucrats and technocrats that dictate our working lives—an ideology that is blind to the complexity of problems and imposes solutions from above. This characterisation of power-elites is derived from Ralston Saul (1993, 2001). Its relevance to schools is discussed in (Goldson, 2023) but, in brief, Ralston Saul argues that power-elites are enslaved by a dehumanising obsession with methods, processes, technology and ‘outcomes’, ‘[making] it impossible for [them] to stand back in order to look upon the shape and meaning of the whole’ (Saul, 2001, p. 292). Their ahistorical, acontextual mentality is manifest in a plethora of failed solutions. The elites are impervious to their own failure, because, lacking all memory, failed solutions are simply supplanted by their replacements. In the context of schools, the failure to stand-back and see the whole in a way that permits plurality, discussion and doubt, has seen a bewildering number of federal, state, regional and local ‘reforms’: a national curriculum (ACARA); a national testing program (NAPLAN); more ‘school ready’ university programs; internships; accelerated training programs for (mid-life) beginning teachers; piece-meal incentives for remote service; school reviews and audits; school re-structuring initiatives; and endless in-service teacher training. To the extent that these ‘reforms’ (unilaterally imposed policies) have led us to the current crisis, to that extent they are clearly failed solutions.

Looking upward, from the bottom to the top, it is not difficult to see why the profession is in crisis. There is a deep-seated rot in our private and public institutions of power. Decades of policy-based evidence, masqueraded as evidence-based policy, has resulted in massive and shameful failure. 12 years after the Gonski Review recommended a School Resource Standard (SRS) for the education of every child, ‘The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) data shows that 98% of private schools are funded above the SRS … and more than 98% of public schools are funded below it’ (Beazley & Cassidy, 2023). Since that landmark review appeared in 2011, a Federal Labour government created a student loan scheme for Vocational Education and Training (VET) that generated massive private profit at the expense of vulnerable young people (Hurst, 2015); a federal coalition government extorted non-existent debts from over 400,000 welfare recipients (Henriques-Gomes, 2023); and Australian universities, responsible for training the next generation of teachers, make record ‘profits’ (Cassidy, 2023a) while simultaneously operating in an ‘appallingly unethical’ way (Anonymous, 2023). The problems faced by our public schools go well beyond the school gates.

So, what is the individual teacher to do in the face of crisis? One response is to leave the profession, and this is happening in droves. According to Federal Education Minister Jason Clare, University enrolments in teaching have fallen 12% over 10 years, only half of students complete their degree, and, of those who finish, one in five leave within three years (Cassidy, 2023c). For those who remain, one thing we can do as individuals is allow ourselves to be guided by true human reason and common sense; to reject a bureaucratic pseudo-rationality that strangles judgement with endless policy and obsessive data collection. Memory is key here. We must constantly remind ourselves that the appeal of teaching is rooted in a certain kind of good relationship between teacher and student. It is the reinvigoration of this ethic that will make the profession more attractive, but it requires a level of trust in teachers (and principals) that is absent in today’s schools. A policy decluttering is desperately needed to make room for good classroom relationships and allow them to flourish.

Gabbie Stroud (2022) gives a checklist of why teachers are leaving Australian schools. Prominent in this list is excessive workload. Jane Caro (2021) tells us that, ‘Far too many of our teachers … drive themselves into the ground’. A Guardian survey reached the same conclusion: ‘Current and former teachers … expressed their anguish at what unbearable workloads were doing to staff and students’ (Guardian Readers, 2021). The problem of excessive workload has been a Teacher Union priority for years, but it is highly resistant to solution. Given the entrenched ideology of large education bureaucracies, the only way to see meaningful and sustained improvement lies with teacher unions. We are each free to interpret the crisis in whichever way we choose, but improvement for teachers can only be achieved by collective action. Action requires analysis. Complex problems have complex causes. Overwork is manifest in many different ways. A partial analysis of this problem runs as follows.

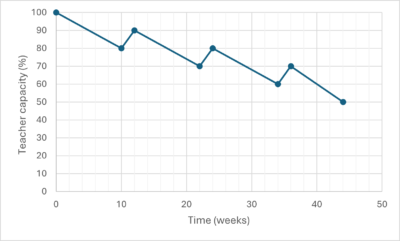

Teacher alienation is a root cause of unsustainable workload. Not long ago employees were persons managed by a personnel department. Nowadays they are human resources, and their value is measured (sic) in human capital. ‘Human is the adjective, capital is the noun. What is meant as a strength is actually an insult’ (Saul, 2001, p. 292). The schematic in Figure 1 reminds us that teachers are not machines. It graphs the energy capacity of a teacher over a 44-week school year and pictures the truism (for teachers) that work capacity is a function of the calendar. There is a significant fall in capacity each term, and the effect is cumulative over the teaching year. Holidays provides some respite, but fatigue nonetheless accumulates through the year.

Figure 1: Effect of teacher fatigue over a school year.

Alienation brings professional disempowerment. One example of this is the management of student assessment. Once upon a time, teachers were trusted to get on with it. Not so today. Today every assignment is saddled with a baggage of bureaucratic rules that make the teacher’s work more difficult. How did this come about? Each jurisdiction can tell its own story. What follows is a sketch of the situation in Queensland. It is important to repeat that this analysis is a partial one. The Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority (QCAA) is responsible for the school curriculum. QCAA is just one source of overwork in schools and the impact of its policies on the classroom teacher will depend on how the policies are implemented in the school. I do not know how much freedom schools have in this, but, given the importance that is placed on consistency, I guess most schools follow QCAA policy to the letter.

Changes to assessment feedback policy provides one example of workload intensification. The QCAA publishes, ‘Strategies for ensuring authenticity of student responses’ (QCAA, n.d.). These include: (1) ‘set an assessment that requires each student to produce a unique response’; (2) ‘collect or observe samples of each student’s work at various stages’; (3) ‘interview or consult with each student at checkpoints’; (4) ‘analyse final student responses using plagiarism-detection software’; (5) ‘use internal quality assurance processes such as cross-marking’. The policy is subtitled ‘Prep to Year 10’. Since the particulars of authenticity-checking will vary from Prep, to Year 7 (start of high school) and into Year 10 (end of compulsory high school), then, for definiteness of discussion, a Year 10 class of 20 students will be assumed.

Consider authenticity strategy (1): ‘set an assessment that requires … a unique response’ (QCAA, n.d.). If this means that work should be written in the student’s own words, then it can be taken for granted. If, on the other hand, it means that each student should work from a unique data set, then it is a 20-fold increase in teacher workload. Instead of mastering one data set, the teacher must master 20.

Consider authenticity strategy (2): ‘collect or observe samples of each student’s work at various stages’ (QCAA, n.d.). A worrying aspect of QCAA English is a highfalutin style that disguises vagueness. In this instance, there is no point collecting samples unless you do something with them—something like read them or mark them, both of which are a lot of work. What about observing samples? What does it mean? What about various stages? What stages? When? How many? A typical pattern here is a checkpoint stage, at which feedback is given, and a final stage, at which work is submitted.

It is useful to recall the way teachers used to give feedback. When I started teaching 18 years ago the only formal checkpointing was in Senior School (Year 11 and 12). It was called monitoring. I collected a work sample from each student, took a quick look, then filed it away. If it was obviously inadequate I contacted parents. Otherwise, if the student failed to submit on the due date I marked and graded the monitored work. I still gave feedback, with due time spent setting up the task, answering queries, and so on. But the feedback was not rigid. It was not dictated by formal procedures from above. It was fairly informal. Its extent and manner was left to me to decide on, and to strike a practical balance between individual and class, student capacity and teacher capacity (class size, ability, teacher time, etc.). This all changed in 2019 when Queensland introduced a new system of Senior Assessment and Tertiary Entrance (SATE). It was designed by Matters and Masters (2014) and implemented by the QCAA. Again, I do not know how much freedom schools have here, but some have now adopted very rigid feedback procedures. One such procedure requires using a separate pro-forma to give feedback. The teacher is no longer allowed to write on the student’s script!

The key thing missing from this QCAA policy is any consideration of workload. How much time does it take to give useful individual feedback, and where will the time come from? Allowing 15 to 30 minutes per script for the higher year levels, it takes 5 to 10 hours to give feedback to a class of 20. This is one or two working days for drafts and another one or two days for the final submission. Where does this time come from? A full-time teacher allocation per week is 19 hours 50 minutes in front of a class, with 17.5 hours (15 lessons) in subject areas. Each of these lessons has to be planned and prepared. There is also a lot of work to do. Is it not common sense that any formal feedback policy must necessarily double workload, a workload that is already over-stretched by a culture of over-assessment? Another thing missing is any prior consideration of the actual benefits to the student of individual and formal feedback against class and informal feedback. The benefits to the student of the pro-forma approach are moot to say the least. Proposals to reduce workload by replacing formal procedures by informal ones, or replacing individual pre-submission procedures by collective post-submission ones, are surely worthy of consideration.

Operational discussion of student feedback procedures misses ‘the shape and meaning of the whole’ (Saul, 2001, p. 292) in the still deeper sense of an uncritical acceptance of assessment itself. Student assessment is deeply rooted in an obsession with measuring (sic) outcomes. In spite of Goodhart’s law that ‘When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure’ (Wikipedia, n.d.a), NAPLAN testing and Senior certification dominate Queensland education as measures (sic) of institutional success. Today, it is no exaggeration to say that high stakes schooling begins with NAPLAN in Year 3, not with SATE in Year 11. The negative effects on teachers of constant testing are implicit in the media sources cited earlier. The negative effects on children, constantly placed under the testing microscope, are evident from the same sources. Consider the recent Australian Senate report on school refusal (Cassidy, 2023b), as well as reports of an anxiety epidemic in young people (Jacques, 2019).

Consider authenticity strategy (3): ‘interview or consult with each student at checkpoints’ (QCAA, n.d.). Much the same difficulties apply here as with strategy (2). 15-minute interviews amount to five hours of work. When do the interviews take place? Is it in class time when the teacher is supposed to be teaching 19 other teenagers? Is it during lunch instead of eating lunch? Is it before or after school? What exactly is a consult if not a kind of interview?

Consider authenticity strategy (4): ‘analyse final student responses using plagiarism-detection software’ (QCAA, n.d.). This raises the ubiquity of computers in schools, of which widespread cheating on assessment is an obvious side effect. The bureaucratic solution to cheating is to use computers to catch computers—a sort of arms race, most recently escalated by Artificial Intelligence (AI). Some adverse workload implications of computer-based schooling include: the de facto assumption that teachers have the requisite expertise; the absence of teacher training opportunities in rostered time; workload creep caused by managing classes in software environments; and obvious, if largely ignored, student behaviour problems created by novel choices—Do I play a computer game or do I complete a maths exercise? Computerisation has also brought large financial costs of licenced software to schools and their long-term dependency on private profit centres. Plagiarism-detection software is not free. In 2019 Turnitin was bought for US$1.75 billion (Wikipedia, n.d.b).

In talking of alienation and disempowerment of teachers, I mean no more than whatever policies significantly affect workload. They are not policies made by teachers, the people who actually do the work, nor even are teachers properly consulted. The important decisions are made by others, typically anonymously, and with little regard to the workload implications of the policies, their necessity, their sustainability, and their health effects on teachers.

Ralston Saul (1993, 2001) argues that a fundamental weakness of institutional elites is their reliance on a context-free instrumental rationality driven by methodological certainty. The only certainty about the current teacher shortage is a lack of understanding how to solve it. I have made some general remarks about causes, including teacher alienation, disempowerment and policy clutter. I have criticised the QCAA for what I see as its damaging complexification and bureaucratisation of school. Of course, it is debatable whether this criticism is accurate. I have given only one concrete example, assignment feedback policy, to try to throw a dim light on the much bigger problem of overwork. It is possible I have exaggerated the negative effect of feedback policies with a false generalisation from my own experience. I have not surveyed my colleagues to report their views. I do not know the wider impact of feedback policies on colleagues, or in other schools across the State. If, however, my criticism is wrong in this particular, I remain convinced that policy creep is a major cause of unnecessary work, and that excessive work, however caused, is a major cause of the current teacher crisis.

There is an ideology in our institutions, public and private, now decades old, that uses policy as an instrument of control. It strangles individual judgment and autonomy by complexifying the workplace with endless rules designed to cater for all possible eventualities. If a Queensland state school teacher does voluntary work in their own private time, the Department of Education has empowered itself to keep a computerised record of it: just in case! Orthodox solutions, based on bureaucratic thinking, amplify our problems rather than mitigate them. Here is a problem. We must collect more data. We must make more rules. Australia is falling behind. We must do more testing. And all the time we know that the appeal of teaching is beautifully simple. At its best it is good relationships between teacher and student; creativity; satisfaction at learning new things that bring pleasure, achievement and empowerment; and the realisation of human potential. Policies in schools should simplify the teacher’s job, not complexify it. They should allow for teacher autonomy. Let teachers teach. Trust them. Policies should be empirical, driven by evidence from the bottom up, and adapted to the needs of each school. Above all, policies should be developed with the workforce—not handed down from above in a climate that silences questioning. Certainty belongs to fanatics. This article is worth writing if 5% of it is worth reading.

Notes on contributor

Doug Goldson graduated from Leeds University (UK) in 1983 with a BA (Hons) in history and philosophy and later from London University (UK) in 1990 with a PhD in computer science. He spent 15 years as an academic computer scientist in London, New Zealand and Australia. For the last 19 years he has worked as a high school teacher of maths, science and English in the Queensland Department of Education, Australia. His interests include the philosophy, sociology and politics of school education.

This work was not conducted under the patronage of the Queensland Department of Education.

ORCID

Doug Goldson ![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9023-0077

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9023-0077

References

Anonymous. (2023, April 10). ‘Appallingly unethical’: Why Australian universities are at breaking point. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/apr/10/appallingly-unethical-why-austra

lian-universities-are-at-breaking-point

Beazley, J., & Cassidy, C. (2023, July 16). Private school funding increased twice as much as public schools’ in decade after Gonski, data shows. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/jul

/17/gonski-review-government-funding-private-public-schools

Caro, J. (2021, February 26). Australian teachers’ workload is snowballing – as their pay lags behind. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/feb/27/australian-teachers-workload-is-snowballing-as-their-pay-lags-behind

Cassidy, C. (2023a, March 3). Australian university sector makes record $5.3bn surplus while cutting costs for Covid. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/mar/03/australian-university-sector-makes-record-53bn-surplus-while-cutting-costs-for-covid

Cassidy, C. (2023b, August 10). Senate report on school refusal recommends subsidised mental health care for students. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/aug/10/senate-report-on-school-refusal-recommends-subsidised-mental-health-care-for-students

Cassidy, C. (2023c, September 23). Australian students shun education degrees as fears grow over ‘unprecedented’ teacher shortage. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/

sep/23/australia-teacher-shortage-education-degrees

Convery, S. (2022, August 7). ‘We need to fix this’: Australian education ministers to address nationwide teacher shortages. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/aug/08/we-need-to-fix-this-australian-education-ministers-to-address-nationwide-teacher-shortages

Goldson, D. (2023). What can (lack of) equilibrium tell us about modern schooling? ACCESS: Contemporary Issues in Education, 43(1). https://doi.org/10.46786/ac23.8292

Guardian Readers (2021, June 29). ‘It is unsustainable’: Guardian readers on the crisis of Australian teacher shortages. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/jun/30/it-is-unsustain

able-guardian-readers-on-the-crisis-of-australian-teacher-shortages

Henriques-Gomes, L. (2023, March 10). Robodebt: Five years of lies, mistakes and failures that caused a $1.8bn scandal. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/mar/11/robodebt-five-years-of-lies-mistakes-and-failures-that-caused-a-18bn-scandal

Hinchliffe, J., & Rose, T. (2022, March 15). Queensland to have one of nation’s worst teacher shortages, modelling suggests. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/mar/16/queens

land-to-have-one-of-nations-worst-teacher-shortages-modelling-suggests

Hurst, D. (2015, October 13). Crackdown on alleged unscrupulous vocational education providers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/oct/14/crackdown-alleged-unscrupulous

-vocational-education-providers

Jacques, O. (2019, January 23). Too stressed to test: Anxious students using doctor notes as exams become too much. ABC Sunshine Coast. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-01-23/stressed-high-school-children-visiting-doctors/10737928

Matters, G., & Masters, G. (2014). Redesigning the secondary–tertiary interface: Queensland Review of Senior Assessment and Tertiary Entrance (2nd ed.). Australian Council for Educational Research.

QCAA (n.d.). Strategies for ensuring authenticity. https://www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/downloads/aciq/general-resources/assessment/ac_strategies_ensuring_authenticity.pdf

Saul, J. R. (1993). Voltaire’s Bastards. Penguin.

Saul, J. R. (2001). On equilibrium. Penguin.

Stroud, G. (2022, June 26). ‘I can’t stay. It’s not enough’: Why are teachers leaving Australian schools? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/jun/27/i-cant-stay-its-not-enough-why-are-teachers-leaving-australian-schools

Wikipedia. (n.d.a). Goodhart’s law. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goodhart%27s_law

Wikipedia. (n.d.b). Turnitin. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turnitin