Introduction

The idea for this paper was first conceived at the PESA Conference in Auckland in 2013, where I organised a symposium with Duck-Joo Kwak, Ruyu Hung and Mika Okabe on the theme ‘Does Place Matter for the Philosophy of Education?’ My presentation, titled ‘Against the Colourless World of Platonic Ideas,’ was inspired by Susan Sontag’s essay ‘Against Interpretation.’ Since then, the concept of colour has remained with me, leading me to continually ask: Is it possible to bring colour into philosophy?

Recently, at the PESA Conference 2024 in Christchurch, I attended a lecture by Jacoba Matapo, a Samoan-born proponent of Pacific philosophy. In her lecture, she beautifully integrated elements of touch (weaving a lalaga mat), sound (reading poetry) and colour (displaying vivid photographs). These experiences encouraged me to think about philosophy with colour as a new and unexplored possibility, one that has long been overlooked by traditional academic approaches.

By ‘philosophy with colour,’ I do not mean philosophy about or of colour, where colour becomes the object of philosophical reflection. Rather, I envision a philosophy that evokes colour. But how can philosophy evoke colour? After all, philosophical concepts are often seen as abstract and devoid of sensory qualities. This is indeed a significant objection, one I hope to address by examining its origins and underlying assumptions.

The Plain of Truth in Plato’s Phaedrus

Let me begin with Plato. He is a towering genius who laid the foundations of Western philosophy. The passage I intend to examine is the second speech of Socrates in Phaedrus. This dialogue is an intriguing work that invites a variety of interpretations. Its central theme is logoi, a term that can be translated as ‘speech’ or ‘discourse.’ The dialogue begins with Socrates meeting his younger friend, Phaedrus, by the riverside of Ilissus – a setting unusual for Platonic dialogues, which are typically set within the city of Athens. Phaedrus is practising a speech written by Lysias, a renowned orator of the time, and Socrates asks him to recite it. The speech’s theme is eros – love, specifically the homoerotic relationships common in their cultural context.

Inspired by Lysias’s work, Socrates composes his first speech, in which he critiques eros as a form of madness. However, he quickly repents and delivers a second speech, in which he praises eros as a form of divine madness. This summary alone highlights the elaborate and complex structure of the dialogue – and this is just the beginning. The second half of Phaedrus transitions into a critique of contemporary rhetoric and an exposition of Plato’s ideal of true rhetoric. Phaedrus is a fascinating work where themes such as rhetoric, madness, eros and nature intertwine seamlessly.

The second speech of Socrates centres on divine love inspired by beauty. This theme is also explored in Diotima’s speech in Symposium and the metaphor of the Cave in Book 7 of The Republic. In these works, Plato describes the ascent of the soul to the highest reality, referred to as the Ideas or Forms. In Symposium and Phaedrus, this is expressed as the Idea of Beauty, while, in The Republic, it is the Idea of the Good. For Plato, beauty and goodness are synonymous, describing the same process: the soul’s journey from the sensory, shadowy world of desire to the luminous realm of Ideas, in which goodness and beauty reign supreme. This spiritual ascent, called paideia in The Republic, is central to Plato’s philosophy. Paideia, often translated as ‘education,’ was rendered into Latin as humanitas and later into German as Bildung, marking it as one of the foundations of Western educational theory. Education and metaphysics are intertwined in it.

What captivates me most about Socrates’ second speech is the description of the region above the heavens, toward which all human souls strive. This is the realm of Platonic Ideas or Forms, described as follows:

Now, the region above the heavens has never yet been celebrated as it deserves to be by any earthly poet, nor will it ever be. But it is like this – for one must be bold enough to say what is true, especially when speaking about truth. This region is occupied by being which really is, which is without colour or shape, intangible, observable by the steersman of the soul alone, by intellect, and to which the class of true knowledge relates. (Phaedrus 247c)

In this realm, referred to as the Plain of Truth (248b), Platonic Ideas such as justice and temperance reside. Souls find happiness here by ‘gazing on what is true’ (247d). This passage represents one of the earliest and most profound testimonies to philosophical contemplation (theoria), an activity Aristotle, following Plato, considered the highest pursuit of the human mind.

The depiction of the soul’s ascent to the world of Ideas is colourful and rich in poetic imagery. One of Plato’s most memorable creations is the analogy of the soul as a charioteer guiding two horses. This metaphor demonstrates Plato’s willingness to embrace poetic imagination, creating a harmony between philosophy and poetry rarely achieved by subsequent thinkers. In this moment, philosophy and poetry are united, forming a fusion that later philosophical traditions could not recapture.

However, a careful observation reveals a tension between philosophy and poetry. Despite the poetic portrayal of the soul’s flight to the Plain of Truth, the destination itself dismisses poetic imagination. It is described as colourless, shapeless, intangible and accessible only through the intellect. In essence, the Plain of Truth denies and rejects the world of the senses, where poetry finds its inspiration.

This separation between the Plain of Truth and the sensible world is known as the Platonic dichotomy. Its most well-known version is the one we find in the metaphor of the Divided Line in Book 6 (509d-511a) of The Republic, which serves as the foundation for the metaphor of the Cave in Book 7 (514a-518b). Philosophy’s radical inclination to ascend from the sensible world to the intelligible realm is at the heart of this dichotomy. It is fascinating to note how Plato employs poetic imagery to describe this ascent: the metaphor of the Cave in The Republic, the erotic ascent to Beauty itself in Symposium (208c-212a) and the soul’s flight to the Plain of Truth in Phaedrus, all attest to Plato’s poetic genius.

However, poetry falters in Phaedrus when it comes to depicting the ultimate destination, the Plain of Truth. This is not surprising, as the Plain of Truth negates sensual experience altogether. The realm of the senses, which provides the foundation for poetry, is thus excluded from this domain.

Light plays a central role in The Republic, Symposium and Phaedrus. The Idea of the Good is represented by the Sun, and the Idea of Beauty radiates brilliance. Yet, understanding the nature of light in the Plain of Truth poses a paradox. In a world without colour or shape, light loses its conventional role and becomes indistinguishable from darkness. It is no wonder that later mystics envisioned the Plain of Truth – often equated with God – as a realm of night and darkness.

In the interplay of light and darkness, philosophy borders on mysticism. At this juncture, the poetic power of philosophy reaches its zenith, but simultaneously, it dissolves into the intensity of pure light, which denies all that is sensible or imaginable. The height of poetic imagination thus becomes its demise.

Here, intellect intervenes. The void left by the absence of the senses is filled by rational thought. Replacing poetic enthusiasm, a sober form of philosophy emerges – represented as dialectics (265c-266c). It is no coincidence that dialectics takes centre stage toward the end of the Phaedrus. Christopher Rowe, in his commentary on the dialogue, defines dialectics as ‘the science of (philosophical) conversation,’ which understands how to ‘collect’ and ‘divide’ in order to reach the essence of things.’

The dialectics of Plato’s late dialogues, such as Phaedrus, Parmenides, Sophist and Statesman, is distinct from the earlier, lively dialogues of Socrates. The early and middle dialogues were enriched by the dynamic exchange of thoughts with idiosyncratic interlocutors such as Protagoras, Gorgias and Alcibiades, focusing on questions of how to live the good life. In contrast, the dialectics of the late dialogues become an abstract exercise in logic, emphasising the analysis and synthesis of concepts. The definition of man as a ‘featherless biped’ (Statesman, 266e) is a notorious example of this late-stage abstraction. Ridiculous this definition may sound, the dialectics that led to it can be interpreted as the first exercise of animal taxonomy. The late dialogues stem from Plato’s attempt to explore the colourless, intangible world of Ideas. It is little wonder that their language reflects the very nature of their subject – colourless, abstract and austere.

Plato’s early dialogues, such as Gorgias, stand out as remarkable works of philosophical drama. In these texts, the intensity of debate and the vibrant character of Socrates as a protagonist dominate the scene. The dialogues of the Middle Period, including Phaedo, Symposium and The Republic combine dramatic and poetic elements, presenting philosophical ideas through lively and engaging conversations.

The description of the earth in Phaedo (110b-111c) is a remarkable testament to Plato’s poetic genius and an eloquent example of philosophy imbued with vivid imagery. This evocative image has captivated later works of science fiction and fantasy, inspiring stories such as Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth and the subterranean realms of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. It also bears a deep connection to Plato’s metaphor of the Cave, reinforcing the theme of reality concealed beneath layers of illusion. Socrates describes ‘the whole earth,’ of which the earth we know is only a subterranean region, as follows.

Up there, the whole earth displays such colours, and indeed far brighter and purer ones than these [colours we are familiar with]. One part is a marvellously beautiful purple, another golden; the white is whiter than chalk or snow, and so it is with all the colours in the earth’s composition, which are more in number and more beautiful than any we have beheld. (110b-d)

Compared to this surface of the whole earth, which Hackforth describes as an ‘earthly Paradise of purity, colour and brilliance,’ the Plain of Truth in Phaedrus presents a striking contrast. Plato’s original image of the higher realm in Phaedo is imbued with vibrant colour, showcasing his unparalleled ability to blend imagination with philosophy.

However, in Plato’s later works, the dramatic and poetic qualities significantly diminish. Socrates, once the central figure, steps back into the role of a disciple or listener. In Plato’s final dialogue, The Laws, Socrates vanishes entirely. While the dialogical form persists, the fierce debates of Gorgias and the dynamic interplay among participants of the Symposium give way to a more didactic style. Philosophy becomes a lecture, guided by figures such as the fictional Parmenides, the stranger from Elea, or the Pythagorean Timaeus.

Among these transitions, Phaedrus vividly illustrates the shift within a single work. It marks the point where Plato begins to move from the lively, dramatic exchanges of his earlier dialogues to the structured, philosophical exposition characteristic of his later period.

By the way, speaking of the colourlessness of language, I am using a metaphor. Of course, language as such does not have colour. What I mean is that language has colour to the extent that it is poetical and evokes sensual imagination. The famous river scene of Phaedrus, in which Socrates and Phaedrus stroll along the river Ilissos and lay down on the grass, is colourful. So is the description of the soul’s ascent to the Plain of Truth. On the contrary, most of the later works of Plato are colourless. So are the works of Aristotle especially his logical treatises. Stoicism and later philosophy then inherited this tendency.

What I said is, of course, a very rough sketch of the history of philosophy. There are also philosophers whose language can be considered colourful, such as Augustine, Montaigne, Rousseau and Nietzsche. It is no coincidence that these thinkers had a strong interest in their individual lives. Their thought bloomed out of the rich soil of individual experience. They were also well-versed in the rhetorical and humanistic tradition, which played a significant role as a rival and critic of the philosophical tradition in the West. However, the mainstream of philosophy has had a tendency or preference to stick to the logical, objective and universal language, which has its origin in the colourless world of Platonic Ideas.

Colourful World of Mahayana Buddhism

Now, to illustrate the significance of the colourless world of Platonic Ideas, I would like to turn our attention to Mahayana Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism thrived in the Northwestern part of the Indian continent, the area in which there was Greek influence after the invasion by Alexander. It was in this region, called Gandhara, that Mahayana Buddhism learned to create sculptures of the Buddha. Due to these historical circumstances, there is a temptation to compare Mahayana Buddhism with Greek philosophy. However, despite some similarities, they are completely different. This is especially so regarding the idea of the universal.

Greek and Western understanding of the universal was shaped by the Platonic concept of Ideas, which we have just examined. According to this view, the universal is characterised by its negative quality. It is timeless, spaceless and colourless. It vertically transcends the sensible world. It is eternal because it is timeless.

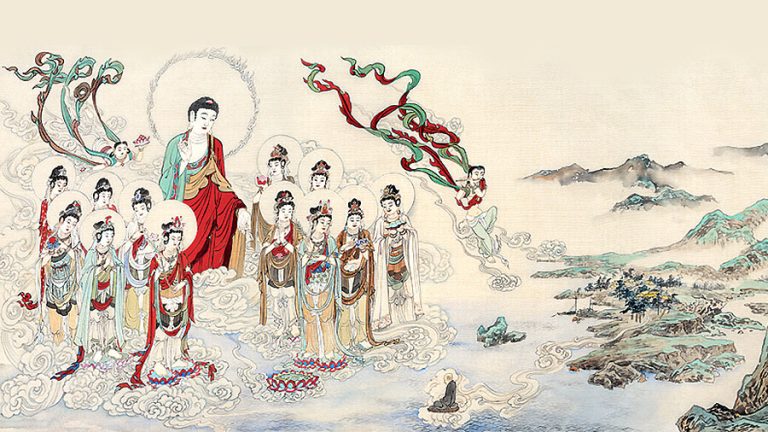

Mahayana Buddhism views the universal differently. Buddha is not just a historical person. Buddhas existed for immeasurable ages and will exist in immeasurable future. To emphasise the universal and eternal nature of Buddhas, Mahayana Buddhism does not say that they are timeless, spaceless, or colourless. On the contrary, it stresses these qualities in excess. There are innumerable Buddhas in innumerable worlds through immeasurable times. Some of them are incredibly huge and very colourful. Their universal and eternal nature does not consist in vertical transcendence of time and space, but in superabundance of sensitive qualities.

As an example of the colourful world of Mahayana Buddhism, I would like to introduce a passage from a Buddhist sutra called the Visualisation of Infinite Life Sutra (観無量寿経). Unlike most major sutras that originate from India, this text was likely composed in Central Asia or China around the 3rd or 4th century CE. Despite its somewhat humble origins, it became one of the most influential texts of Mahayana Buddhism due to its poetic instructions for contemplating the Pure Land through 16 distinct visualisations. This sutra profoundly influenced East Asian Buddhism, shaping the teachings and practices of prominent figures such as Shan Dao (善導, 613–681) in China and Honen (法然, 1133–1212) in Japan (Tsukamoto & Umehara, 2014).

An incredible richness of vivid and sensual imagery marks the description of the contemplation in the Visualisation of Infinite Life Sutra. It is no surprise, then, that this sutra greatly influenced East Asian arts. In Japan, the most exemplary representation of this influence is the Byodoin Phoenix Hall 平等院鳳凰堂 constructed in 1052 in Uji, near Kyoto.

Here is an example from the tenth contemplation, the contemplation of Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva 観自在菩薩:

The palms of Avalokiteśvara’s hands form fifty billion assorted colours of lotus blossoms. The hands have ten fingertips, and each one of these fingertips has eighty-four thousand patterns, verily, like a printed design. Each one of these patterns has eighty-four thousand colours, and each one of these colours has eighty-four thousand lights. These lights are supple and illuminate everywhere universally, whereby Avalokiteśvara’s jewel hands rescue the sentient beings. (Hanya, 2018)

The Visualisation of Infinite Life Sutra outlines sixteen contemplations, including those of the Sun, water, the ground, jewel trees, jewel ponds and palaces with towering structures. These contemplations are brimming with colourful imagery, reminiscent of the poetic visions in Phaedo. Interestingly, while Plato himself dismissed such poetic imageries in pursuit of the Plain of Truth, they reemerged in Mahayana Buddhism on a grander scale. In their opulence, the imageries of the Visualisation of Infinite Life Sutra stretch the boundaries of our imagination to their limits, transcending the horizontal plane of worldly experience.

Alternative Views of Transcendence

The depiction of the Pure Land stands in stark contrast to the description of the Plain of Truth in Phaedrus. While the Plain of Truth is devoid of colour, the Pure Land overflows with vibrant hues. What accounts for this difference? The divergence stems from the contrasting visions of transcendence.

Both the Plain of Truth and the Pure Land lie beyond the realm of ordinary experience, transcending this world. The term ‘beyond’ translates the Greek epekeina, a word Plato employs in The Republic (509b) to signify the elevated status of the Good, which is beyond being or reality (tes ousias epekeina). However, the direction of transcendence in these two visions differs fundamentally.

Platonic transcendence is, metaphorically, vertical – it ascends above the temporal realm. As such, it is eternal, abstract and universal, transcending both time and space. The absence of colour in the Plain of Truth is not incidental but a necessary consequence of this vertical transcendence. In contrast, the Pure Land’s transcendence engages with a richness of colour that reflects a wholly different conceptualisation of the ‘beyond.’ Its uniqueness does not consist in timeless eternity but in the richness of temporal, spatial and sensual qualities beyond measure.

The Plain of Truth and the Pure Land present us with two alternatives of transcendence. The one strives to reach the eternal, abstract and universal truth; the other tries to enrich our vision of life by intensifying timely, spatial and sensual qualities. Both views deserve respect because they created what we call culture by providing us with a vision of life. This said, it seems to me that the academic discourse of our age has biased preference to the abstract and universal. This preference can suffocate us by detaching us from our experience of the natural and cultural world.

In this situation, colour may provide us with an interesting approach. Our discourse may need to be more colourful. For this, we should cultivate our sensitivity to colour. The natural world is full of colour. The change of colour accompanies the change of seasons. The colour of nature is never simple but consists of infinite gradation and variety. Our artificial world can also show the amazing aspects of colour. Great paintings of the world can teach us to view the world colourfully.

The sensitivity to colour extends far beyond its literal meaning. I have already addressed the metaphorical nature of colour, but let me elaborate further. Metaphorically, colour can symbolise that which resists being entirely subsumed under form – those elements that are elusive, fluid and dynamic. The natural world, the body and emotions can all be seen as metaphorical ‘colour’ due to their fleeting and indefinable nature. These are aspects to which Socrates paid little attention in Phaedrus. He remains indifferent to the beauty of the plane tree by the Ilissus River, his focus firmly fixed on conversations within the city (230b-d). While he is drawn to physical beauty, he dismisses it as inferior (253d-257a). Similarly, he seeks to elevate rhetoric – often entangled with emotion – into a philosophical rhetoric rooted in reason (259e-262c).

These domains – nature, the body and emotion – are often associated with what Nietzsche termed the ‘Dionysian.’ In fact, much of what we now call culture falls within this realm. Cultivating a sensitivity to colour, both literally and metaphorically, can deepen our appreciation for the local and temporal aspects of nature and culture, enriching our engagement with the world.

Further Exploration: A Cinderella Story of the Word 色 (sè) in East Asia

Thus far, I have sought to illustrate both the significance and the limitations of the colourless world of the Platonic Ideas by examining the peculiar depiction of the Plain of Truth as colourless and contrasting it with the vibrant portrayal of Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism.

In the following discussion, I aim to further explore the theme of colour, approaching it from a lateral perspective. Specifically, I wish to delve into the fascinating history of the word色 (sè) in East Asia – a tale that could be likened to a Cinderella story within the realm of intellectual history. In this narrative, the word 色 begins as a humble maidservant but is elevated to the status of a queen, thanks to the transformative influence of figures such as Confucius and Kumarajiva, who play the roles of benevolent guides in this remarkable journey.

The text I would like to consider is Heart Sutra 般若心経, which contains pivotal phrases. The following four lines merit special attention:

色不異空

空不異色

色即是空

空即是色

Colour (Body) is not different from Emptiness

Emptiness is not different from Colour

Colour is Emptiness

Emptiness is Colour.

Heart Sutra (Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya-sutra) is one of the most essential texts in Mahayana Buddhism. It contains only 262 Chinese characters and serves as a concise distillation of the prajñāpāramitā (Perfection of Wisdom) literature, a vast collection of teachings centred on the realisation of śūnyatā (emptiness), a cornerstone of Mahayana philosophy. It was composed between 300 and 350 CE.

Throughout history, Heart Sutra has been translated into Chinese numerous times. Among these translations, the most influential is the version completed by Xuanzang (玄奘, 602–664 CE) in the mid-seventh century. After returning from India with an extensive collection of Buddhist sutras, Xuanzang undertook this translation as part of a state-sponsored project supported by the powerful Tang Empire. His version of Heart Sutra, along with his other translations, was widely disseminated across regions such as China, Tibet, Mongolia, Vietnam, Korea and Japan.

However, it is important to note that another significant translation, Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra of the Great Mantra (摩訶般若波羅蜜大明咒經), was completed approximately 250 years earlier by Kumarajiva (鳩摩羅什, 350–c. 409 CE). Notably, Kumarajiva rendered the key term rupa as 色, a choice later adopted by Xuanzang in his own translation.

Kumarajiva was a remarkable figure who played a pivotal role in introducing Nāgārjuna’s philosophy of the Middle Way (Madhyamaka philosophy 中観) to China (Tachikawa. 2003)He also made significant contributions to the development and dissemination of Pure Land thought within Chinese Buddhism (Tsukamoto and Umehara, 2014).

The phrase 色即是空 (‘colour is emptiness’) is a translation of the Sanskrit expression rūpaṃ śūnyatā. The term rūpa has been interpreted in various ways in modern translations. Thich Nhat Hanh, an influential Vietnamese Buddhist scholar, renders it as ‘Body,’ while Hajime Nakamura, a renowned Japanese scholar of Buddhism, translates it as ‘physical phenomena’ (物理的現象). Therefore, my choice to translate 色 as ‘colour’ is philologically inaccurate.

However, it is undeniable that the word 色 carries strong associations with colour in East Asian cultural and linguistic contexts. This raises an intriguing question: why did translators like Kumarajiva and Xuanzang choose 色 to render rūpa? This question invites deeper reflection on the interplay between linguistic translation and cultural adaptation in the transmission of Buddhist thought.

To fully appreciate the boldness of translating rūpa as 色, it is helpful to consider the nuanced meanings of this character in ancient Chinese culture. The Chinese character 色 embodies a rich spectrum of connotations in classical Chinese, reflecting its complexity and versatility. According to Kanjigen (漢字源), a renowned dictionary of Chinese characters published in Japan, 色 encompasses meanings such as sexual desire, facial expression, outward appearance and colour – this last sense notably including the five primary colours: red, yellow, blue, white and black.

The character’s pictographic origins (象形文字) intriguingly suggest a depiction of a sexual act between a man and a woman, underscoring its strong erotic associations in early usage. Yet, in literary and philosophical contexts, its other interpretations – particularly those related to appearance and the visual qualities of the world – carry equal weight.

The Analects of Confucius offers seven examples of the term 色 and its multifaceted meanings, demonstrating its richness and versatility in classical Chinese texts. These instances reveal how 色 operates across different contexts, ranging from physical beauty to moral conduct, and even to the subtleties of human demeanour. The visible aspect of 色 as colour appears in The Analects 10.8: 不食悪色, where Chin translates it as ‘food with a sickly colour,’ and Ames and Rosemont similarly note, ‘If the food was off in colour […] he [Confucius] would not eat it.’

In the context of sexual desire, 色 appears in passages that reflect the tension between physical beauty and moral values. For example, The Analects 1.7 states: 賢賢易色. Chin translates this as, ‘If a person is able to appreciate moral worth as much as he appreciates physical beauty,’ while Ames and Rosemont simply render 色 as ‘beauty.’ Similarly, in 9.18 (吾未見好徳如好色者), Confucius remarks, ‘I have never met a person who loved virtue as much as he loved physical beauty.’ These examples might seem to suggest a negative view of physical beauty, given its association with desire. However, Chin suggests a more nuanced interpretation: Confucius and Zixia are not condemning physical beauty itself but cautioning against valuing it over virtue and wisdom.

More often, the term 色 conveys meanings related to appearance and facial expression. There are four cases. In The Analects 1.3: 巧言令色鮮矣仁. Chin translates this as, ‘A man of clever words and a pleasing countenance is bound to be short on humanity,’ where 色 is understood as ‘countenance.’ Ames and Rosemont similarly translate it as ‘appearance.’ Here, Confucius criticises the insincerity behind a pleasing exterior; however, he does not condemn appearance itself.

Another example is found in 2.8: 色難, which Chin interprets as ‘the difficult part is the facial expression,’ emphasising that filial piety involves not just actions but also the expression of genuine affection and respect. This interpretation deepens in 16.10, where Confucius lists ‘amicable expression’ (色思温) as one of the ‘nine things the gentleman gives thought to’ (九思).

In The Analects 10.3, Confucius’s demeanour is described as solemn (色勃如) when summoned by his ruler. Here, a solemn expression, together with other bodily demeanours, is a part of ritual performances. These usages underscore the Confucian emphasis on the facial expressions or outward appearances of the gentleman (君子). Whether amicable or solemn, 色 plays a crucial role as an essential component of Confucian ritual or propriety (礼).

This overview of the Confucian use of 色 shows that despite its humble and even erotic origins in early pictographs, 色 evolved into a concept of significant ethical importance. This transformation continued with Kumarajiva’s decision to use 色 as the translation for the Sanskrit term, rūpa, further enriching its meaning within Buddhist philosophy. The journey of 色 from its erotic origins to its elevated status in Confucian and Buddhist thought illustrates its profound adaptability, offering insights that resonate across cultural and historical contexts.

What astonishes me most about Kumarajiva’s translation is that scholars of Buddhism rarely express amazement or wonder at its boldness. This is because they take for granted that 色 corresponds to the Sanskrit rupa. In doing so, they overlook the fact that the same character carries a wealth of meanings – encompassing colour, facial expression and even erotic beauty. Few words are so emotionally charged. To repurpose such a nuanced term for rupa, a dry and metaphysical concept, was a remarkably audacious choice.

Kumarajiva’s translation not only made the concept of rūpa more accessible to the common people in China but also enriched the philosophical and cultural discourse surrounding it in East Asia. Through this ingenious choice of terminology – arguably bordering on philological mistranslation – the impermanent physical world of phenomena came to be subtly associated with the fleeting beauty of colour.

A full exploration of the rich cultural role that the word 色 took on in East Asia would require an entire book. I am far from qualified to undertake such a task. However, I can offer a glimpse of its significance by citing a famous poem by Ono no Komachi. Not only was she a celebrated waka poet of the Heian period, but she was also renowned for her beauty. (In Japan, she is counted among the three great beauties of the world, alongside Cleopatra and Yang Guifei!) She sings:

The hues (色) of cherry blossoms have faded away in vain,

While I spent my days in wistful contemplation.

Here, the word 色 (iro) refers not only to the colour of the blossoms but also alludes to her own appearance and erotic beauty. At the same time, the fading of colour echoes the Buddhist notion of impermanence – ‘色 is emptiness.’ It is remarkable how the Confucian and Buddhist nuances of 色 intertwine in this deceptively simple poem, composed by a female poet at a time when Chinese scholarship was largely restricted to men.

This paper was initially presented as a special lecture at the Asian Link Philosophy of Education Young Scholars Seminar, held at Seoul National University on February 8, 2025.