Introduction

There is a phrase I often encounter in conversations about AI and creative labour: Only good writers get AI to write well. It’s meant to reassure – to affirm that human expertise still matters, that machine fluency alone doesn’t suffice. But I’ve begun to worry that the phrase misreads the dynamic. It casts the writer as the primary agent in a scene where agency is already distributed and where the criteria for what counts as ‘writing well’ are being subtly reconfigured by the very systems designed to assist.

This essay begins from a different angle – not with a defence of authorship, but with a question about the quieter conditions under which legibility takes form. Not what writing is, or even what AI does to it, but how certain rhythms of thought become writable or unwritable, finished or still moving, within environments increasingly shaped by machinic feedback. If generative systems now help determine what writing is allowed to sound like – what registers as coherent, fluent, or complete – then the question is not whether they help or hinder, but what becomes possible to think in the process.

Rather than generalise from a theoretical remove, I take a situated approach. I begin with a paragraph I once wrote about Mark Twain’s encounter with the typewriter – an encounter that already stages the epistemic and affective uncertainties of writing with a new machine. I then pass that paragraph through a generative model and linger with the difference. What follows is not a comparison in search of proof. It does not resolve into loss or gain. It stays with texture: where tension recedes, where rhythm hardens, where recursive motion collapses into legibility. In this sense, it reads for what Barad might describe as the agential cut – that moment where meaning settles into form, and something else begins to slip from view.

I describe this approach as a form of epistemic AI literacy. Unlike more instrumental definitions – prompting strategies, output assessment, genre adaptation – this is not a toolkit. It is a mode of attention, one that registers how epistemological assumptions are encoded in the systems that now shape writing. To read this way is not simply to evaluate what the model produces but to palpate the difference between writing as recursive event and writing as flattened surface. What matters, then, is not just what we write, but how writing becomes writable under machinic conditions.

The structure of the essay follows this recursive logic. It begins with Mark Twain – not merely as a historical figure but as a writer whose encounter with the typewriter indexes broader shifts in cognition, embodiment and meaning. From there, I move into my own writing about Mark Twain and the AI’s version of that same text. I don’t offer this as a binary but as a layered field of transformation. The aim is to trace where and how thought becomes text – and to ask what happens when systems begin to anticipate that transformation in advance. I close with a brief return to pedagogy – not as application, but as a site in which these tensions might become perceptible.

The Artifact as Event

Mark Twain, Typing and the Scene of Technological Rewriting

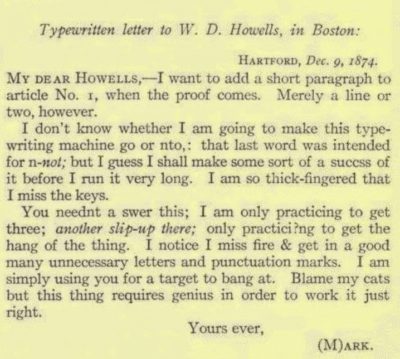

Before returning to Mark Twain’s letter, it is worth pausing over the version that now circulates. What we typically encounter – online, in retrospectives – is not the original output from Mark Twain’s Remington No. 1, but a typeset rendering. This version, with its mixed case and regular spacing, reflects editorial interventions that smooth over the technical and physical difficulty of early typing. Twain’s machine produced only uppercase characters, required manual spacing and introduced a mechanical cadence shaped by interruption. That cadence has been replaced by a contemporary rhythm of fluency, which reads not only as more familiar but more coherent. Yet this fluency is not incidental. It enacts a transformation in which struggle is erased and replaced by seamlessness – substituting the event of writing with its idealised afterimage.

What looks like a faithful reproduction is instead a recursive cut: not a misrepresentation, but a reconstitution of legibility itself. In Karen Barad’s terms, it is an agential cut – an act of boundary-making that organises what counts as meaningful signal and what is cast off as machinic noise. The reprint doesn’t follow the act of writing; it conditions how that act becomes recognisable. The friction of Mark Twain’s original – a hesitation that marks the entanglement of body, voice and resistant medium – has been formatted into a text that reads as if it had always been fluent. That loss is not catastrophic, but it is structural. It tells us how systems come to anticipate meaning before we arrive, and how ease becomes the medium through which we forget what writing once asked the body to do.

Mark Twain’s 1874 typewritten letter to William Dean Howells, as published in Mark Twain: A Biography by Albert Bigelow Paine (1912).

Reading the Rewrite

AI Fluency and the Loss of Hesitation

Earlier in this piece, I included a paragraph that was still in process. It wasn’t quite a thesis, and I didn’t intend it to be. I had written it to stay close to the scene I was describing – Mark Twain at the typewriter, encountering a medium that scrambled fluency and made authorship feel unstable. The language I used was imprecise by design. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say that I was testing what forms of precision remain possible when thought is being reshaped mid-sentence. I wasn’t offering a stable idea so much as documenting a movement: recursive, off-balance, not quite finished.

That original paragraph is as follows:

Mark Twain’s encounter with the typewriter stages more than a shift in medium; it initiates a scene of mediated self-recognition that is both disorienting and oddly amused. The letter he writes is not simply a record of adaptation but a site of rupture – of authorial self encountering the machine’s resistance, its refusal of seamless inscription. ‘I miss fire & get in a good many unnecessary letters and punctuation marks,’ he writes, performing not just technical difficulty but a kind of authorial doubling: the breakdown of control becomes legible as part of the act. These aren’t simply errors. They are a form of self-inscription through misfire, the typographic stutter becoming part of the textual ‘I.’

And, yet, this is not a scene of anxious loss. Mark Twain’s tone is comic, even self-mocking. Like the pseudonym he performs – Mark Twain/Clemens, already a split subject – the author here embraces the strange deferrals of meaning introduced by the machine. His body and voice register friction, but they also experiment with it. What emerges is less a lament than a speculative play with authorship under new conditions. The Remington No. 1, with its top-mounted platen, quite literally delayed the appearance of text – it was ‘blind writing,’ where the words emerged only after the keys were struck. In this mechanical delay, the typewriter splits the author’s relation to their own writing. Mark Twain’s ‘I’ writes but cannot immediately see what it has written. Authorship becomes a loop, not a line.

In this scene, the interface does not just mediate the hand – it redistributes cognition across a feedback delay. Mark Twain is trying to learn the machine, but the machine is also teaching Mark Twain how authorship now requires a strange kind of trust in what cannot yet be seen. The joke is not incidental. It’s how the system reveals itself. What had been immediate – pen to page, hand to trace – now becomes recursive. Mark Twain’s struggle is not with the loss of self but with its reconstitution in a circuit he no longer fully controls. But neither is he trying to recover it. If anything, he seems to enjoy the disorientation, laughing as he types himself into a form he cannot quite claim yet still performs.

I then asked ChatGPT to rewrite it. I wanted it ‘clarified.’ What came back was neither inaccurate nor simplistic. But it shifted something structural. The rewrite reorganised the paragraph’s internal logic, compressed its recursive movement and reformatted provisional claims into structured assertion. It didn’t misinterpret so much as resolve. And that resolution altered the texture of thinking. I found myself reading not a restatement but a version that had become linear, final, legible in ways the original deliberately resisted.

Mark Twain’s early interaction with the typewriter offers a revealing glimpse into how new technologies can reconfigure authorship. His letter reflects not just mechanical difficulty but a transformation in how writing is experienced and understood. The mistakes – misspellings, errant punctuation – are not hidden or corrected. They remain on the page as part of the process. Mark Twain doesn’t present himself as fully in command of this new tool. Instead, his language suggests a writer feeling out the contours of an unfamiliar interface, adjusting in real time. ‘I am only practising to get the hang of the thing,’ he writes, signalling not just experimentation but a moment in which fluency becomes uncertain, and authorship feels provisional.

Yet this uncertainty is not portrayed as a crisis. Mark Twain’s tone is light, even amused. The difficulties are acknowledged, but they are not lamented. If anything, the letter seems to accept error as part of the transition. Mark Twain does not insist on recovering the smooth authority of handwriting; he allows the new form to show its seams. The typewriter, with its delayed visual feedback and rigid mechanics, interrupts the immediate connection between thought and inscription. What appears on the page is shaped not only by the writer’s intention but also by the constraints of the machine. And in that gap, something changes. Writing becomes less a direct extension of the self and more a negotiation between hand, key and delayed result. Mark Twain’s authorship in this moment is marked not by mastery but by accommodation – by a willingness to be reshaped by the device he’s learning to use.

I’m still not entirely sure what changed, only that something did. Reading the rewritten paragraph, I didn’t feel disagreement so much as a loosening of the tension I’d been working through. It was no longer the paragraph I remembered – not because its content was wrong, but because the strain had gone missing. What I had written wasn’t resolved. It had moved uncertainly, trying to register something as it formed. But the rewrite arrived already formed. It didn’t misrepresent the idea; it just came too close to completing it.

One change that lingered was the substitution of ‘mistakes become part of the message’ for what I had written as ‘meaning arrives through error.’ At first glance, the difference is minimal – both suggest that something unintentional becomes meaningful. But the AI phrase is declarative. It offers a summary, a kind of narrative closure: the error has been incorporated, and its function resolved. My version wasn’t meant to declare anything. The phrase ‘arrives through error’ wobbles intentionally. I didn’t write that meaning is error. I wrote that it arrives – suggesting a temporality, a process, something not yet stable. The original sentence was an opening; the rewrite made it an outcome.

Another shift occurred in how the author-machine relation was framed. I had written: ‘Mark Twain is trying to learn the machine, but the machine is also teaching Mark Twain how authorship now requires a strange kind of trust in what cannot yet be seen.’ The AI version renders this dynamic as: ‘Mark Twain isn’t simply adapting to the machine – the machine is reshaping how he writes.’ It’s not wrong. But it simplifies a relation that, in my original, was unstable, even a little uncanny. I had tried to convey the affective dimension of that lag – how the Remington’s blind typing suspended the author’s control, how writing preceded visibility. The rewritten version flattens that recursive disjunction into a more familiar form of technological influence: ‘reshaping how he writes.’ That’s a functional description, but it lacks the opacity – the delay and deferral – I was trying to stay with.

There’s also a tonal adjustment in the way authorship is cast. I wrote that ‘Mark Twain’s ‘I’ writes but cannot immediately see what it has written.’ That sentence carried a quiet vertigo. I wanted the reader to feel the disjunction, the estrangement of the self from its trace. The AI version instead says: ‘It signals a moment when fluency falters, and something new begins: an authorship shaped not by control, but by constant readjustment.’ Again, this isn’t inaccurate. But it’s resolved. The faltering has become a pivot. The loss has been placed in service of a new model of authorship. In my version, the authorship that emerges doesn’t replace the old one. It remains unsettled – caught between effort and accident, between gesture and ghost.

And, yet, I don’t mean to cast these differences in opposition, as though mine was the correct account and the other a distortion. The rewrite doesn’t erase the ideas. It absorbs them. That absorption is precisely what makes it difficult to object. What it produces is a clean articulation of a thought that had not yet become clean in my own writing. That cleanness is not an error. It’s a difference in epistemological rhythm – in how understanding forms, how it moves, how it makes itself known.

The original didn’t try to explain Mark Twain’s confusion. It tried to inhabit it. It stayed close to his comedic ambivalence, his willingness to wrestle the typewriter not just as a tool but as a medium that disorients. The AI version translated that ambivalence into legibility. That’s not a betrayal. It’s a function. But the shift matters because it reveals something about how systems trained on completion treat disorientation: not as a mode of thought, but as a threshold to be passed through.

Mark Twain, in that original letter, isn’t narrating a resolved insight. He’s palpating a change that is still underway. That’s the term I keep returning to – palpation. Not metaphorical, but physical. The sense of testing, pressing, feeling for what resists. The AI version doesn’t press. It glides. And in that gliding, something subtle is lost – not the idea, but the hesitation that made the idea thinkable in the first place.

Epistemic Cuts and the Conditions of Knowing

What these ruptures begin to expose is not merely a difference in phrasing but a line within a broader epistemological shift. This shift does not arrive in a single gesture or historical break but emerges through accumulations – through the rephrasing of ‘meaning arrives through error’ into ‘mistakes become part of the message,’ or the compression of a recursive structure into a polished takeaway. These are not cosmetic edits. They illustrate how systems designed to assist in composition can also delimit how meaning becomes thinkable. The AI’s rewrite becomes exemplary of what Karen Barad describes as an agential cut – not a neutral observation, but a boundary-making act that silently determines what counts as meaning and what gets left behind. Such a cut is not imposed from outside but generated within the entanglement of expression and reception, where significance is continually negotiated.

Karen Barad’s cut both separates and entangles. It draws a line, but it also shapes what is drawn into relation. The AI does not erase difference; it instantiates a certain mode of difference – smoothed, anticipatory, resolved. That resolution is often hard to name, but it is felt. Reading the AI’s rewritten paragraph, I sensed something had been closed off. The closest approximation was the feeling of palpation. Gilles Deleuze uses the term to describe a tentative, affective encounter with what resists definition. Palpation is not guessing, nor is it analysis. It is a mode of contact with something forming, something just beyond articulation. It offers no confirmation, only the sensation that a shape might emerge if one lingers in the right rhythm, under the right pressure. What the AI removed was not content but that encounter with form before it coheres.

To read the AI rewrite is to notice that this mode of encounter has been foreclosed. The structure remains, but the movement is gone. What once felt recursive – ideas circling, revisiting themselves – has been ironed into a more linear progression. The AI doesn’t falsify. It anticipates. It arranges. And in doing so, it installs a regime of legibility in which meaning arrives too early, too easily. That ease is not without cost. It risks rendering illegible those parts of cognition that do not yet know what they are trying to say.

This is why the return to Mark Twain matters. His typewritten misfires are not simply technical failures. They register a moment in which writing becomes distributed – across hand, eye, machine. His admission, ‘I miss fire & get in a good many unnecessary letters and punctuation marks,’ is not just confessional. It is performative. It names a point where cognition exceeds intention, where the interface introduces its own rhythm, its own resistance. Mark Twain, like Gilles Deleuze’s palpator, doesn’t resolve this difficulty – he stays with it. He wrestles with delay, blind inscription and unfamiliar spacing. His authorship is scattered across these frictions. And yet, there is no sense of loss in his account. There is laughter. There is play. There is a speculative openness to what writing might become when intention is no longer the only guide.

This recursive, co-authored dynamic is what an epistemic AI literacy might begin to take seriously. Not a fluency in command or control, but an attunement to how systems reorganise the emergence of thought. Epistemic literacy asks us to read not just for argument or correctness, but for where insight gets foreclosed, where roughness is smoothed, where difficulty is managed out of view. It does not seek mastery. It seeks sensitivity. Palpation, in this sense, becomes a method – not metaphorical, but real. It names a way of moving through mediated writing that remains alert to friction, to delay, to the places where meaning strains against its own articulation. And it is in these strains that thought begins again – not cleanly, but with weight. Not resolved, but real.