photo – Coatepec, Mexico – children writing at home

PART 1: From ‘Rights’ to ‘Literacy’

Michael: When was your book on rights in education published and when did you begin to focus on literacy?

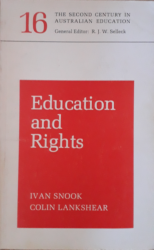

Colin: My Master of Arts thesis topic was The Right to Educate and the Right to be Educated, 1972, University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Ivan Snook supervised and we were going to use it for a book in a 1970s series edited by Richard Peters. Things changed and Ivan got a contract for a smaller monograph than had originally been envisaged, Education and Rights (Melbourne University Press 1979). It was quite different from the original thesis, and I thought at the time it would have been nice to develop some of the arguments in greater depth, especially the ones around possible educational alternatives. On the other hand, the book highlighted the tension between suggesting possibilities for change and knowing such change was never likely to happen — even if it were desirable. Some of the proposals we advanced in the book reflected a kind of liberal idealist kite flying that was popular at the time. For example, lowering the legal school leaving age to 13 and offering young people opportunities to experience the world and come to thoughtful decisions about what they might like to become, and to consider what they would need to learn in order to become that. Such proposals were grist for lines of critique based on Marxist theory that emerged in Australasian educational philosophy from the latter 1970s.

Michael: How did you arrive at writing a thesis on rights in education, and what kind of work was it?

Colin: In the course of writing my thesis I came to understand my craft as partly involving learning how to analyse the concepts of rights, and what it means to educate and be educated, in terms of looking for what we can say about those concepts without ending up in glaring linguistic or logical contradictions; and to proceed from that basis to identify substantive actions, processes, distributions, and the like that seem consistent with the conceptual analyses. These wider aspects involved selections from values and theories that could be argued for on the basis of ethical, political, or psychological considerations. I also saw my craft as being concerned with identifying distinctions between different historical categories of rights and identifying some key aspects of their etymology and traditions. For me, being an educational philosopher was never about conceptual analysis alone, or even predominantly. This was largely thanks to Ivan, who saw engaging with ethics, psychology, and the history of social and political ideas as integral to developing any substantive position on educational matters. Mine was an apprenticeship to argumentation and to following lines of argument where they lead. But most of the substantive values, and practices construed as consistent with those values, drank deeply from the well of Liberal Rationalism, which Jim Walker (1984) subsequently identified as the ideological heart of analytical philosophy of education.

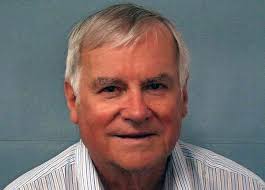

Ivan Snook

It was an interest in argumentation that led me to Ivan. As a first year undergraduate in Education, I listened, captivated, as he laid out lines of argument for and against state funding for private schools based on religious belief. Never the sharpest knife in the drawer, I nonetheless saw very clearly that this lecture was not about content; it was about competing lines of reasoning. I knew I was interested in that and wanted more of it. That lecture was my first step on the way to writing a thesis and co-writing a book in education and rights.

In many ways I should never actually have arrived at either place. To get to university I needed to take a teacher studentship to support myself. Builder’s labouring in the holidays was not enough. As a studentship recipient I was bonded to train as a teacher upon completing my degree, and to teach a year for each year of my studentship. By my second year of undergraduate study I knew I did not want to be a teacher. I discovered though that if my grades were good enough I could defer while I did a Masters degree.

That I got to do a Masters specialising in philosophy of education was largely because Ivan had gained my attention from the outset. But in my second undergraduate year I luckily met another person who influenced me greatly and in the same direction. I had seen Jae Renaut perform as a folk musician and when he showed up in Education 2 lectures, we routinely sat together. When Ivan came in to do a block of lectures addressing Richard Peters’ account of the concept of education, I was struggling to get it, but knew there was something to get. Jae was studying philosophy (not available to me because I was on a studentship). He helped me get my head around what I was not seeing. That was the beginning of the road that led to my specialising in educational philosophy. We’d spend hours hacking out ideas and alternative positions on essay topics. To a very considerable extent, Jae was my undergraduate university education. And in a conversation a couple of years later he effectively pointed me toward trying to become an academic.

Strapped for cash while studying, I welcomed Jae’s invitation to join him as a cleaner at one of the university halls of residence. There were endless conversations, on the job and after. One day we were working away, talking about life, and Jae said “You know, given that one must be something, one might as well be an academic.” That stunned me. I had never thought about it. Jae had, “there aren’t many jobs going, but having a First Class Masters might get a step in the door.” When I eventually knew that I would be graduating my Masters with First Class Honours I asked the studentship committee if I could defer to do my PhD. They informed me that I could indeed defer, and that lecturing at university was an option for paying back my bond.

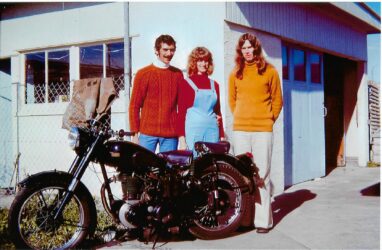

Jae and I had spent many hours talking about conceptual analysis, and we had our critiques of its limits so far as substantive philosophy was concerned. But we learned to do it as well as we could and developed a sense of where you looked (in ethics, political theory, history, etc) for the larger vision. Ivan sharpened many things for me along the way. Shortly after I completed my Masters, Jae and his partner decided they were leaving to live overseas. He was selling up and asked if I wanted to buy anything he was leaving behind. He had a 1950 BSA 500 single cylinder motorcycle in parts that he had planned to restore. It was complete and original, and Jae said he could give me the name of a friend who would help me learn how to do the restoration. With much help I restored the 500 single before I had even learned to ride. I learned and got hooked.

At the end of the Masters coursework I received an A+ in Ivan’s Masters paper, and it was a no brainer that I’d do my thesis with him. He asked what I wanted to do. I said “Anything you are interested in. The topic is not so important to me. What is important is that I want to learn to be like you, to be able to think and argue and write like you do; and my best chance of that is to work with you on something you are genuinely interested in.” Ivan was interested in Rights at the time, and so “Rights” it was.

At the end of the Masters coursework I received an A+ in Ivan’s Masters paper, and it was a no brainer that I’d do my thesis with him. He asked what I wanted to do. I said “Anything you are interested in. The topic is not so important to me. What is important is that I want to learn to be like you, to be able to think and argue and write like you do; and my best chance of that is to work with you on something you are genuinely interested in.” Ivan was interested in Rights at the time, and so “Rights” it was.

Michael: What was your doctorate in philosophy of education about?

Colin: When it came to lining up a PhD project in philosophy of education Ivan said it was time for me to do some full time study in the Philosophy Department, so sorting a topic early would help with deciding which Philosophy courses would best support the thesis work. We agreed that Richard Peters’ argument as in his paper ‘Freedom and the development of the free man’ would be a good focus, since my informal discussions with Jae had concluded, with Hume, that reason was the slave of the passions.

Like my work on ‘Rights’ I stuck with a loose version of analytic philosophy that involved a lot of inquiry about concepts. My inquiry was framed by the question of what a philosopher might say about the relationship between access to liberty and becoming a free person. I understood freedom as a paradigm case of what W.B. Gallie called “essentially contested concepts”, and found Gerald MacCallum’s triadic relation model of freedom a useful frame for sorting some of the conceptual issues. Moreover, while there was some mileage to be had from asking questions like whether liberty was better understood in terms of constraints to wants or constraints to choices, I saw none to be had from analyzing the concept of a free person. It seemed to me that this was an ideal to be built from the ground up, based on a valuative standpoint for which one made supporting arguments.

In the thesis I did what I had not done in my account of rights in education: I argued at length against liberal rationalism and came up with an ideal of free personhood that consisted in getting one’s wants sorted out into a coherent and manageable ‘set’ that allowed for a satisfying and fulfilling life. While this was the antithesis of rationalism it was still quintessentially liberal in respect of its individualism. And it was still a classic case of philosophy of education as an exercise in what Kevin Harris called “supportive rhetoric”. It didn’t help that Harris’ book was published just months before I finally finished the thesis.

That was not the only ‘existential’ complication for me so far as the thesis was concerned. A couple of years before I completed, Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish appeared in English, with all its implications for discussing freedom. My thesis was too far advanced by then to consider changing horses in midstream. That decision was easy enough. Far more problematic was the issue of bypassing Paulo Freire, having discovered him. It was not an issue in the sense that my topic was already in place, had passed through the confirmation hoops, was already under way, and did not formally require taking account of Freire’s position. Rather, it was difficult in the sense that, after reading Freire, I wished I had been doing a different thesis. By then I was enjoying my first academic full-time job and ongoing employment at the end of my fixed term appointment required getting the thesis completed as quickly as possible.

As destiny would have it, my date with Paulo Freire was just around the corner. The brute reality is that doing the PhD almost did me in. For long periods it simply tormented me. I felt out of my depth for months at a time, and remember reading and re-reading Rousseau’s Social Contract for weeks on end, simply to be able to nail a lynchpin paragraph. By the time I had finally finished and defended my thesis in 1979 (Freedom and education: an application of ethics, political philosophy and philosophy of mind to some of the problems associated with freedom in education) I was really in no shape to be riding motorcycles. And just six weeks or so after my thesis defense — in the early hours of 2 February 1980 — I was on the BSA 500 motorbike I had bought from Jae at the outset of my doctoral study, in the wrong place, at the wrong time and, definitely, in the wrong ‘state’.

BSA & hair 1979

Michael: So when and how did you make the shift to “Literacy”?

Colin: I spent much of 1980 in hospital as my orthopedic surgeons mended 9 fractures between my right knee and my ankle. The first month passed in a haze as we beat off gangrene and passed through four long surgical procedures. When the haze subsided, friends, students and colleagues who knew I had been reading Freire told me on their hospital visits that the Sandinista Government in Nicaragua had launched a national literacy crusade and a local organisation was co-ordinating support. They had heard that the approach to teaching literacy was based strongly on Freire’s work, with him as a consultant. That got me back reading Freire, and following the campaign as best I could.

When finally out of hospital and back at work I began developing courses on literacy and education in revolutionary societies, as a way of shifting academic direction and getting more of a political focus into my courses. This very much reflected the influence of colleagues in PESA who had been mounting their critiques of analytic philosophy of education for several years by then. I found Kevin Harris’ 1979 book Education and Knowledge absolutely compelling. It awakened a political interest in me that had really been asleep after my first year at university. And Robert Mackie’s 1981 Literacy and Revolution: The Pedagogy of Paulo Freire provided an ideal text for my shifting teaching interests.

But the event that on its own did most to push me into writing about literacy was absolutely random. It came from deep out of left field. Some time in 1982 a colleague at Auckland passed me a copy of the Adult Performance Level Study (APL) that had been undertaken at the University of Texas on behalf of the US Office of Education. It provided a model of functional literacy on the dimensions of content and skills, and it appalled me. All I could think of at the time was “talk about tools for constituting people as beings for others.” It would doubtless have helped enhance the capacity of marginally literate people to be more efficient consumers, and to be able to find their way around bureaucratic offices and documents. But it downplayed writing, and seemed to me would actually mask the potential reading and writing have for developing critical acumen and stimulating effective (political) action to promote one’s own interests and others like oneself.

My outrage — it burned — moved me to write a piece on functional literacy that critiqued the APL study and developed an alternative conception of functional literacy, trading on Freire’s idea of our ontological vocation as human beings. I gave Aristotle’s idea of function a twist, arguing that “our ontological vocation to be more fully human” could be construed as our function as human beings. From there it was a simple matter to run a Freirean line on literacy as an ideal of functional literacy.

Michael & Rima Apple

Michael & Rima Apple

I presented it at the 1983 PESA conference where some kind people said complimentary things about it. Around 3 weeks after the conference I was blown away to receive a letter from Michael Apple who was at the conference, although I had not met him there. He wrote saying he had shared the paper with his grad students and they thought it was a worthy intervention. Michael encouraged me in no uncertain terms to publish the paper. I experienced that as an impressive act of collegial generosity, and what we would now call mentoring. And as far as my academic work was concerned it changed everything. It actually set my academic life on a wholly new course. It resulted in two published papers on the theme of functional literacy, but also got me writing about literacy in Nicaragua and the difference between the ethos of the literacy campaign and the ethos of the APL study.

Ivor Goodson

This work still drew substantially on the combination of concept building and style of argumentation that I had arrived at in my PhD, but now also referred to field work, interviews and artifacts to advance a standpoint on literacy as a cultural phenomenon. By 1986 I had thought about literacy quite a bit. One day there was a knock on my office door. It was Ivor Goodson, on a visit to New Zealand. I had never met Ivor, although I knew some of his work. He asked if I would like to go for a beer and he told me he had read something I had published and there was a paragraph in it he quite liked. (I asked if he was sure it wasn’t just a long sentence.) Ivor asked what I was currently working on, and I told him literacy and revolution. He then asked if I would be interested in writing a book for a series he was editing. Ivor added that titles need three things, so it would be necessary to get something like schooling into the fame as well. Within a week I had a contract to write Literacy, Schooling and Revolution (Falmer Press, 1987).

At the outset of writing that book I found Brian Street’s 1984 Literacy in Theory and Practice. It hit me like a wall and, along with the work of Silvia Scribner and Michael Cole, seemed to me absolutely ‘right’ and, happily, consistent with Freire. Since then I have maintained a broadly sociocultural approach to understanding literacy as a cultural phenomenon.

Literacy, Schooling and Revolution (1987) did well. Within a couple of years I was known beyond Australasia as someone who wrote about literacy from a broadly sociocultural perspective, with strong Freirean inflections, and who used this conceptual and theoretical frame to interpret and evaluate empirical cases of literacy in classrooms and communities. This was an absolutely unplanned and entirely unpredictable trajectory given where I was at the end of my doctorate. I had pursued an academic job as a philosopher of education to earn a living and pay back my studentship bond. And now I was writing about literacy and making connections with people around the world as the book garnered many favourable reviews and was one of the American Educational Studies Association’s ‘outstanding recent books’ for 1988.

But I could not have written it without a challenge provided by some students in a course I was teaching in 1984. They asked “how do you know how accurate the reports are about the Nicaraguan Literacy Crusade?” So I made a trip to Nicaragua over the university summer vacation in 1984-85, and spoke to people who were involved at all levels. These included international observers, librarians, people who had taught in the campaign, and people who had participated. In Nicaragua I gathered every document and artifact I could find, recorded conversations on tape, and met two remarkable people who spoke English. One was a cadet reporter from the newspaper Barricada who had participated in the English language version of the campaign on the Miskitu Coast. The other was an Ecuadorian researcher named Rosa María Torres, Adviser to Nicaragua’s Vice Ministry of Adult Education 1981-1983.

Rosa María Torres

Rosa María took some of my audiotaped interviews, kept them after I returned home, translated them into English, and posted me the translations from Managua. Her generosity amazed me and I remain deeply grateful. I find it hard to imagine anyone experiencing greater collegial solidarity and generosity than I received on my random trajectory to becoming a kind of literacy researcher. My experience was beyond humbling, and I regret that space does not permit me to acknowledge here the parts many other people played along the way. I nonetheless do remember and thank you all, regularly.

End of PART 1.