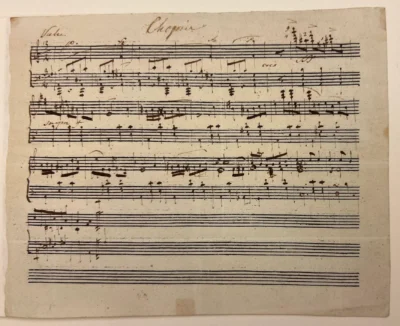

An opera singer texted me: ‘Look at this scrap of paper.’ Javier C. Hernández, music reporter for the New York Times, unearths something nearly unfathomable. ‘It was much smaller than I had imagined – a pockmarked scrap about the size of an index card.’ A cellphone. An image. A photograph taken of this scrap of paper. Chopin? Could it be? Scribbled, tiny handwriting? Notes on a score? How could it be?

In a vault at the Morgan Library & Museum, this pockmarked piece of paper as small as an index card was recently discovered to be a piece – never before unearthed – by Chopin. There is a photo of Chopin’s score in a link in the New York Times. As small as an index card and pockmarked. Profundity, gravity, suffering. Chopin’s Waltz – albeit short – stops you in your tracks. Leaves you breathless. There are several links in the New York Times. One is a photograph – taken with a cell phone – of the scrap of paper. Clicking on the second link, one can listen to Lang Lang play what is on the scrap of paper. Listening, watching. Something tiny scribbled on a scrap of paper, a small score.

Lecia Rosenthal, editor of Radio Benjamin, reminds us that for Benjamin the aura has an ‘optical unconscious,’ but the radio changed that. What is heard gives itself to colour – auras that appear and disappear. Notes leave an aura. Some say colour, or sound-colour, overtones produced by wooden instruments. Plastic instruments (like synthesisers) do not produce auras, for there are no overtones. Some might debate this.

Jeffrey Kalberg, a Chopin scholar, said that when he looked at the tiny, scribbled signature of Chopin and played the score, the piece was ‘jaw dropping.’ Mind-blowing. Indeed, it is jaw-dropping for many reasons. A scrap of paper has altered music history. The sheer gravity of something so small, Chopin’s brief score – the size of an index card – lost in the stacks, missed, overlooked. Who knows why. Haunting. Not one extraneous note. Plato’s logographic necessity: all the puzzle pieces are tightly woven without extraneous embellishment. Chopin’s piece – phonologographic necessity – a puzzle tightly woven, with no unnecessary embellishments. I always wondered how Chopin wrote such perfect music.

Finding this small scrap of paper reminds me of Derrida’s The Post Card, a book that has haunted me, a book that stays with me all the time. I can’t stop thinking about The Post Card. At the university we were asked to post our office hours. I posted my office hours on a postcard next to a photograph of Freud mixed up with hundreds of photographs. Good luck finding my office hours. A language game: Wittgenstein.

Derrida’s book on The Post Card begins, ‘Yes, you were right, henceforth, today, now, at every moment, on this point of the carte, we are but a minuscule residue ‘left unclaimed’: a residue of what we have said to one another, of what, do not forget, we have made of one another, of what we have written one another.’ A postcard could signify a ‘minuscule residue’ of what we say and do not say to one another. Office hours. Posted on a postcard, next to a photo of Freud. And hundreds of other photos. A game of cat and mouse. A language game: Wittgenstein. A scrap of paper, a few notes, a signature scribbled in tiny letters: Chopin. What does the tiny signature tell us? Is it really his? Or is this scrap of paper attributed to Chopin? The experts say it is really Chopin’s signature. It sounds like Chopin’s music. It is Chopin. How can it not be? But why was it lost so long in the stacks of a library on Madison Avenue at 36th Street?

Text messages are short, small. An opera singer texted me: ‘Look at this scrap of paper!’ Text messages, scraps of paper. Still half asleep, I hesitated, exhausted by the day’s demands. Text messages, forms of utterance, seemingly small, are much more than that. Derrida reminds us, ‘what we have made of one another.’ Text messages tell stories about what we have made of one another, what traces are left after the text gets deleted, if any. Like Derrida’s Post Card, like Chopin’s scrap of paper, the text messages sent, received, ignored, deleted – thoughts ‘left unclaimed’ – hesitations and exhaustion[s] – might seem like ‘minuscule residue’ and, yet, if one pays close attention, jaw-dropping remarks, coded, hidden – misunderstood. It is very easy to misread a text message. We are in too much of a hurry. What ‘residue’ is left over from a text message? Text messages, like postcards, like small scraps of paper, are allegories. There are many stories to be told, much to spin off, things that do not coincide with the literal text, or the literal postcard, or the literal scrap of paper. Benjamin’s ‘optical unconscious’ and phantasmagoria coded, photos from cell phones, pieces of paper, text messages. Sending some strange signals from a beyond, an unconscious floating signifier.

Derrida’s The Post Card, Chopin’s lost scrap of music, text messages not deleted, can become – over time, archival utterances of tremendous weight. A word. One word or another carrying signals. Send – address profundity, gravity. It is easier to ignore one word. Pay attention: text messages might be ignored, discarded or missed.

Like Chopin’s Waltz unearthed on Madison Avenue at 36th in the stacks of the Morgan Library, Derrida’s opening sentences to The Post Card are jaw-dropping. What we say to one another, ‘what we make of one another,’ ‘residues.’ We do not even know what we are saying at the time. Over time, re-turning, re-finding old text messages create an archive, a memory-text. For, we do not have to say much to one another to say a lot. Even if we do not speak to one another for long periods, we are still, in a way, speaking through silence. Just as there are rests in Chopin, there are rests in saying, in utterance, in text messages. To say, I need a break from texting, or I need to get off of social media, I need a rest from saying or commenting. The rest matters. Taking a rest. It is the rest, in music, that matters most. Ignoring rests by covering them over with too much pedal ruins a piece. It can ruin a piece of music. And what if that piece of music happens to be Chopin’s unearthed Waltz? We might take care of notes the way we take care of and take care with words. Derrida and Chopin take care of and take care with words and notes, respectively.

What re-turns, a lost score, a buried text message, a text re-read thousands of times haunts, stuns. I keep thinking about and returning to this discovery, Chopin’s Waltz, found in 2024. Music history has just changed. That a book haunts, that the opening sentences of Derrida’s The Post Card keep coming back to me. His words I hear repeatedly. Coming back to Derrida again, I wonder what it is about his work that so resonates. He is a philosopher-poet. But there is more to it than that. And what it is –that pulls me back to Derrida, I cannot say. I keep his books on my bookshelf so I can find them. The first thing I see in the morning, upon waking, are Derrida’s titles. I keep his books close. I come back to his work all the time.

A seminar on Derrida in the mid-1990s at LSU altered the trajectory of my intellectual life. I heard that Derrida had come to LSU before I got there. Curriculum studies scholars have drawn on Derrida’s work for decades. Derrida is particularly attractive to professors of education because he was concerned with the university, the pressures of university life, the problems of academic freedom, the Conflict of the Faculties, Kant’s worries Derrida took to heart. Derrida’s work on the seemingly small – the Post Card – generates unending discussion, scholarly commentary. Both in the philosophy of education and curriculum studies, Derrida’s work ‘lives on.’ Derrida is the Chopin of philosophy.

And yes, scores of commentaries continue to be written on Derrida’s work. Chopin is still played. Chopin made the newspaper just the other day. Musicians are talking about Chopin with much excitement. I got a text message from an opera singer: ‘Look at this scrap of paper!’ Who would think that today Chopin would generate so much discussion outside of circles of musicologists? 2024 marks the 20th anniversary of Derrida’s death. He continues to generate discussion, commentary and controversy. Mind-bending paradigm shifter, Derrida changed the landscape of academia. The academy is slow to change. The academy lags behind intellectual movements. It seems that the academy has to play catch up. German academicians did not understand Benjamin, nor did they understand Derrida. The question is not about getting it, the question is about not getting it, not understanding it. Groundbreaking breaks things. Shattering the taken-for-granted. Shall we shatter the I to get it?

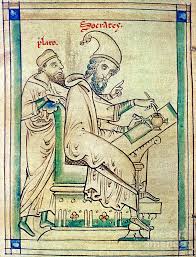

Socrates and Plato did not want to be understood. Who wrote what? Who was the scribe? These are questions Derrida raises in The Post Card. The same questions are being raised about the newly discovered Chopin Waltz. Is it really his? Is this his signature? It sounds like Chopin. Is it attributed to Chopin? The Morgan Library lists Chopin’s newly found waltz as being attributed to Chopin. But Chopin scholars seem to think that this is Chopin. Who wrote this? Why was this piece lost in the stacks? Why was it found now, in 2024?

A postcard is small and seemingly insignificant. Derrida teaches that this is not always the case. Derrida ‘stumble[d] across’ a postcard in the Bodleian Library: ‘I’ll tell you about it. I stopped dead.’ Socrates, Plato. Who writes for whom? Who transcribes what? And how would we know? Socrates, it is said, did not write, but the postcard – Derrida unearths – tells a different story. Plato stands behind Socrates, Plato’s hand points over Socrates’s shoulder like a didactic schoolmaster. But Socrates did not write anything, so they say. Or did he? Or does it matter who wrote what? Did Plato write for Socrates? Did Socrates write for Plato? Or are the two merged as-if Heinz Kohut’s’ ‘self-objects.’ The object that is the other becomes part of the self, hence a self-object. The postcard unearthed in the Bodleian library made Derrida ‘stop dead.’ Jaw-dropping. Derrida’s book on a postcard is 521 pages long (in the English translation). Wittgenstein: how small a thought it takes to fill a life. Derrida: ‘We are a miniscule residue left unclaimed.’

The minute we say or write something, words vanish. What is left of that vanishment? A minuscule residue? It could also be that what we leave behind in our work – whether books or musical scores – multitudinous secrets, who wrote for whom? Exhaustion[s], hesitations[s] and yes, unfathomable suffering[s] – coded in text. Written words, utterances, whether spoken or written, musical scores tell stories, but they only tell so much. I. W. Winnicott might ask: what do you do with ‘minuscule residue’? Or what does that residue do for you or to you? If you keep returning to the same books, the same writers, the same scores, the same musicians, what does that say to you, and what do you use books and music for? Psychologically, that is.

What is fashionable in music changes. Things come and go, trends come back, vanish only to come back differently later on. It is the case that modern concert halls demand loud pianos, sharp pianos with bite and grit – concert grands 9 feet long. Concert grands – like the Steinway model D – are meant to blow the roof off. One of the reasons pianists get injured is because larger pianos sometimes demand higher action (on the keyboard), which puts too much pressure on the hands. If I need a hammer to play the piano, something is wrong. Nietzsche philosophised with a hammer. But that is different. Hammering to make his point because no one listens. Or so it seems. Pianos weren’t always this way. Concert halls seem to keep getting larger demanding louder sound from pianists and string sections, brass, you name it. Pianos are getting louder and harsher as concert halls keep getting larger. Why do we need everything to be so loud? Horns, New York City street cabs blasting at one another. Shouting at football games. TV commercials seemingly yelling at you when you go to the fridge.

However, Max Richter, a composer influenced by Philip Glass, tones the piano down, softening the sounds. Moreover, Richter takes things slower. His universe is slow. Slowing down and softening things might counter this historical era where things are too loud, too fast. Pianos are being altered – dampened. Softer sounds. Is the music world trending backwards, returning to the era of intimate salons? Pianos during Chopin’s time were not loud. They, too, were dampened, softer, lighter action, played like butter. No hammer necessary. Re-iteration of The Four Seasons (Vivaldi) by Max Richter haunts. Taking up the old and making it new. Syncopations not quite expected. Different syncopations change Vivaldi in profound ways. Vivaldi becomes haunting minimalism. Small changes in the score radically alter the way the music sounds. Half-steps down – a pattern in lament dirges – get your attention. Whereas first to fifth and back again seems almost trite. Ending on the fifth instead of the first – leaves listeners hanging. Thinking and? And then? You are just going to leave me dangling over a precipice? Small moves – especially downward – chromatically alter sound radically. The postcard, the score no larger than an index card, softer sound, taking the time to take time and just stop. Take a rest. Make something of the rest. The residue, the rest in the score, the rest of the day.

Records are re-played over and over, generating memories. Books are re-read over and over, generating thoughts. Dennis Sumara – a literary scholar and curriculum theorist – has often commented on how often he has re-read The English Patient. There are books and writers we return to time and time again. Like music, books that are re-read allow us to re-think and co-write in the margins a counter-text or co-text, or commentary that, over time, changes. Marking up scores over decades of study, say Chopin’s Preludes, tells a story about the markings, how they have changed, what they once meant and what they might mean now. The smallest markings on a score tell stories that might hold secrets and ‘residue’ about who we once were, or who we once thought we were, or wanted to be or become. Markings on musical scores tell stories but tend to be ignored or scratched out over time, confusing the musician. Markings are important because they can change the way music gets interpreted. Textual commentary, small markings keep the score alive, give the score a history, a memory, markings are archives ignored. They are sometimes written over, crossed out, fingering changes. Residue of psyche buried in markings, especially when they have been crossed out like graffiti. In that crossing out, there are contradictions, paradoxes and puzzles to figure out.

I have played Chopin’s Preludes millions of times. But still, it takes a lifetime to play such short pieces and play them well. I do not know too many pianists who do play the Preludes well. They are deceivingly complex. There are a few pianists whom I would consider poets of the piano. Poets of the piano can play Chopin’s Preludes well. Philosopher-poets, like poets of the piano, are also rare. I can name a few. Derrida is a poet-philosopher. He might also be considered a painter of words. The Truth in Painting. Like Derrida, Chopin is a sound-painter, a poet-philosopher. Sounds have colours. So, too, do words.

An opera singer texted me and said: ‘Look at this scrap of paper!’ On that paper, a sound-painter emerges from the dead. A piece of paper that got buried in a museum. Something that curators either missed or overlooked. And then everything changed. Music history has changed. I hesitated to look because of exhaustion and the dawning of another round of the everyday grind. Paying attention to hesitation[s] is as important as finding scraps of paper, markings on musical manuscripts, a single word in a text message. Of course, this was Freud’s teaching. In the not said, things are being said. It is in the rest that the music comes to life. Without rests, music would be unbearable. But taking a rest – from text messages, from social media – from conversation and dialogue does not mean that things are dead, or there is nothing more to say. Rests are necessary. But resting places, like graveyards, are for the dead. But the dead have a way of coming back to life. The symbology of resurrection becomes important. Can one resurrect oneself every day amidst the horrors of yet another election cycle? Can one resurrect one’s work after so much pushback and policing? Having to get up over and over again. Just getting up becomes utterly exhausting. Sometimes you just need a rest.

Chopin’s index card & Derrida’s postcard cut through the everyday in what Peter Fenves might call an ‘irrevocable interruption of everything that has hitherto appeared.’ Interruptions, like text messages, can be ignored, deleted, trashed, saved. Interruptions when playing or writing can get on your nerves. I’m so bent. Silence. However, interruptions become part and parcel of the work at hand. Using interruptions, rather than ignoring them, might enrich or alter a text in unthought ways. Text messages can interrupt what you are doing. And they might even annoy you. But, every now and then, a postcard, a scrap of paper turns up. A text message: ‘Look at this scrap of paper!’ Hesitations no more.