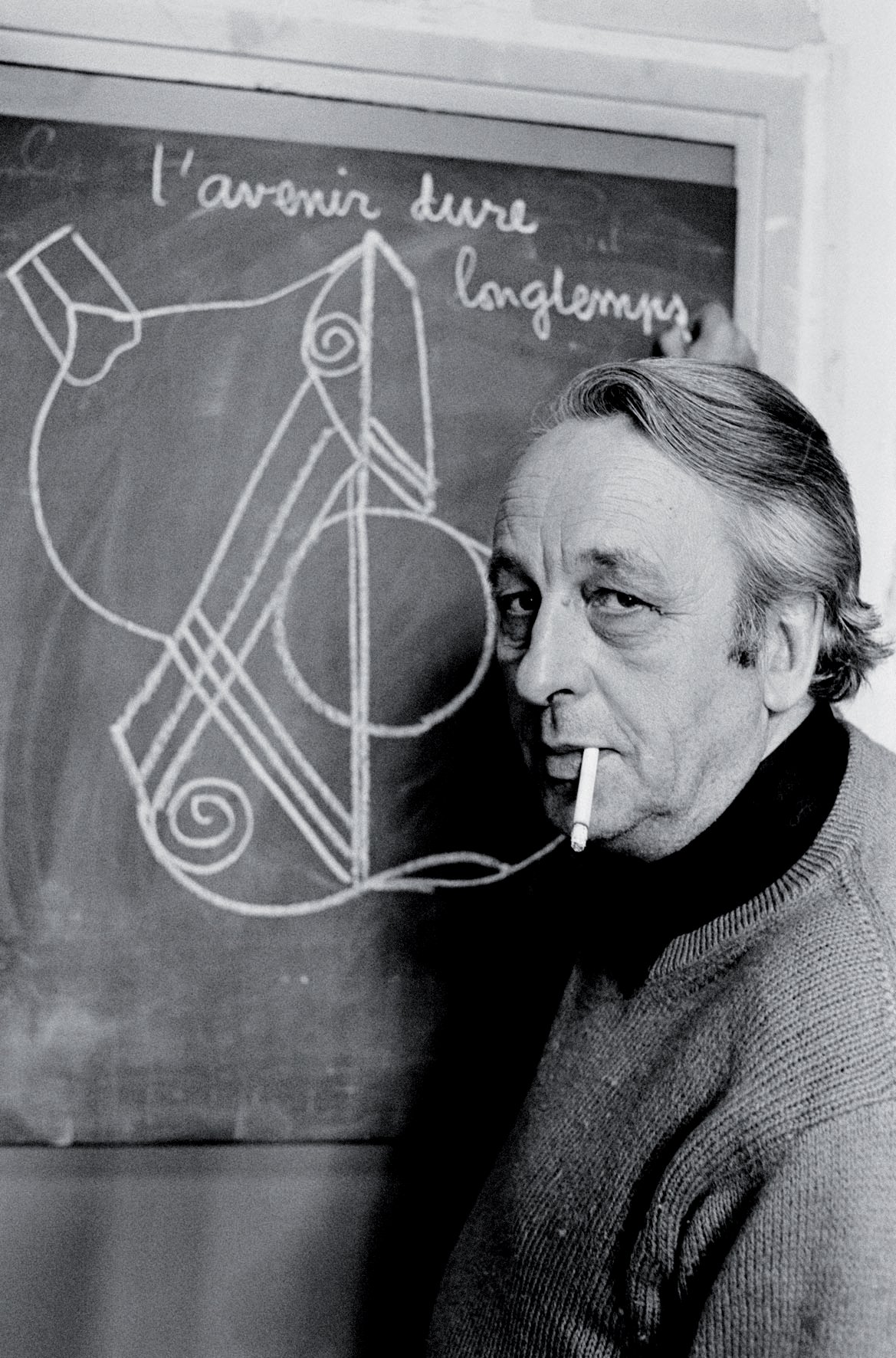

The spectre of Althusser weighs like a nightmare on the minds of living Marxists.

So writes living Marxist David Neilson, cleverly riffing on Karl Marx’s famous aphorism: ‘The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living.’ But Neilsen has a problem with this. I am a living Marxist. I am also one who, forty something years ago, strongly embraced Althusser in my writings (see, especially, Harris, 1979), and notwithstanding that my large scale change of allegiance to Gramsci, as detailed in my fourth book (Harris, 1994) still continues (Harris, 2012), neither now nor at any time over the intervening period have I felt the weight of any such nightmare. Nor do I believe philosophy of education should. Let me explain why.

Neilsen’s paper is both detailed and rigorous. It is the sort of thing that Marxist scholarship, given its common tendency to become reduced to polemics, is all too often sadly lacking, and it is certainly one that would have been welcomed at the time and in the milieu in which my writing bore its strongest Althusserian influence. And, at that time, a very important point would (hopefully) have been quickly recognized: we are/were each writing about a ‘different’ Althusser.

Neilsen’s focusses on a number of aspects of Althusser’s work – mainly Althusser’s debt to his mentor Bachelard, his development of a theory of knowledge without a subject, his fixation on ‘identifying’ an epistemological break in Marx’s work, and his books Reading Capital and For Marx. All of these present suitable grist for a philosopher’s mill. Bachelard is at best problematic; the search for Marx’s legendary or mythical (depending on where you stand) ‘epistemological break’ has led too many philosophers into nightmare-inducing swamps; and Reading Capital from the moment it was published had good philosophers scratching their heads. But note: I said, quite deliberately, grist for the philosopher’s mill. I was not reading Marx and Althusser strictly as a philosopher, but rather as a philosopher of education. The distinction (at one time, the basis for derision) is very important.

Let me, therefore, consider the position of the philosopher of education. But, first, I should note, and will elaborate on later, that on the other side of the philosophy/education nexus there was/is also widely-held antipathy to Althusser and the belief that, rather than shining light on certain educational issues and debates, he has really just muddied the waters and, as with the philosopher’s claim, led folk into murky, impenetrable depths. Consider, then, the following from Ken Johnston: a self-declared ‘left-wing radical’ academic from what I call the ‘gut-feeling’ school of sociology, who professed strong concern with the status quo of schooling and education in Australia:

a radical critique of schooling was not gained from reading abstruse theory or participating in an Althusserian study group! I knew, from painful experience, that there was something fundamentally wrong with the social relations of teaching and when, some years later, I read Goodman, Holt, Neil [sic], Tolstoy and the others I felt as if my private convictions had been publicly confirmed.

Educationists, as should be obvious, ought and have to do better than that; but, now, having introduced both a philosopher and an educational sociologist bagging Althusser, I turn to how I believe a philosopher of education should approach the matter, and, through the process, I will hopefully extract Althusser from their negative clutches.

Philosophers of education generally do not, and universally should not, abrogate any single responsibility of the philosopher. But they have their own focus: ‘education,’ of course. So, in sharing the philosopher’s rigorous examination of sources they are looking for and examining both the same and different things. With Marx, they would look particularly for his theory of knowledge and for references to schools and teachers. And their reading of Althusser would find its fertile ground in the ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses’ essay in Lenin and Philosophy, rather than in Reading Capital or For Marx. There would be this different but not inferior ‘reading emphasis’ (Neilsen, the philosopher, does not mention the ISA essay).

This particular ‘reading emphasis’ could, of course, be dangerous if it took its own focus out of the overall context, indulged in convenient glosses, employed insufficient rigour or relied on private convictions and the like. It’s a tough job, and to make it tougher the philosopher of education’s task with Marxism is not a straightforward one. First, as philosopher, there is the long and daunting task of engaging with the totality of the Marx oeuvre. And having sufficiently mastered that in order to be competent enough to proceed, there follows a disillusioning realization: Marx didn’t say much directly about schools, teachers or education. In fact, there is just this single short bit tucked away towards the end of the first volume of Capital:

a school master is a productive labourer, when … he works like a horse to enrich the school proprietors. That the latter has laid out his capital in a teaching factory, instead of a sausage factory, does not alter the relation.

But any minor delight that this might bring about is immediately shattered by the simple realization that Marx was writing about a long-gone era before state-controlled public schooling was even on the horizon in much of the capitalist-developing world, wherein the school proprietor has now been replaced by the State as the major provider of schooling and the largest employer of teachers. And, in this historical development, the ‘relation’ has certainly been altered. The schoolmaster (hereafter, ‘teacher’) is no longer a productive labourer – defined by Marx in a later volume as one who exchanges surplus value against capital, but rather an unproductive labourer who exchanges surplus labour against revenue. Thus, the one tiny mention has, in fact, become a can of worms.

Here, the philosopher of education might try to get those worms together again (as I did – try, that is – over a period of half a decade, which led to Teachers and Classes (1982) and other exploratory academic papers), or possibly delve back into the Marx oeuvre to find less direct passages to guide an ensuing investigation. They will appear. For instance, the Eighteenth Brumaire will throw up the familiar passage:

Men [sic] make their own history. But they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves but under circumstances directly found, given and transmitted from the past.

That locks in the ‘historical’ bit. Then, from the Preface to the Contribution of a Critique of Political Economy comes:

The mode of production of material life conditions the social, political and intellectual life process in general. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.

That big call of Marx serves our philosopher of education doubly. First, it cements the ‘material’ aspect and thus lays down the twin foundations for historical materialism. And, secondly, by referring to the ‘intellectual life,’ it pokes the bear of the transmission and gaining of knowledge, and thus schooling and education. Things are looking better, and they even begin to shine when our philosopher of education finds, in The German Ideology, the very well-known passage:

The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas: i.e., the class which is the ruling material force of a society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal has control at the same time of the means of mental production…. Insofar, therefore, as they rule as a class and determine the extent and compass of an epoch, it is self-evident that they do this in its whole range, hence among other things rule also as thinkers, as producers of ideas, and regulate the production and distribution of the ideas of their age; thus their ideas are the ruling ideas of the epoch.

Thus, a beginning, and an end. For the philosopher of education, the beginning: the State (read State power) or ruling class, transmits ruling class ideas and conditions the intellectual life of the citizens. But, within the Marxist oeuvre, also the end: there’s precious little if anything about how do they do it and get away with it. It is now necessary to turn to the secondary literature … and there go the weekends!

Of course, one form of ‘secondary literature’ was always available: what I called the ‘supportive rhetoric.’ Here sits the State-sanctioned material: reports, glosses, enquiries etc., which detail how well the education system is operating, and how the government might seek, and always is seeking, to improve the status quo, along with the academic material which poured out empiricist studies which bolstered State claims, historical tomes which diverted attention elsewhere, and on occasions proffered mild criticism which the State could handle and pledged itself to attend to. Even grand theories of ‘human nature’ served as apologies when schooling didn’t seem to do all that much for the proletariat, as with Matthew Arnold’s off-hand pronouncements in the Victorian era, viz:

The mass of mankind will never have any ardent zeal for seeing things as they are: very inadequate ideas will always satisfy them.

And

Knowledge and truth, in the full sense of the words, are not attainable by the great mass of the human race.

The remarks were unashamedly repeated by R. S. Peters a century later in what was issued as ‘objective’ analytic philosophy:

The majority of men are geared to consumption and see the value of anything in terms of immediate pleasure or as related instrumentally to the satisfaction of their wants as consumers.

This sort of stuff, especially when it comes from respected intellectuals, has always served capitalist societies well, and did so particularly in the rebuilding phase immediately following WW2. But there came a time when the long-underlying cracks began to surface in the new social cohesion (it became too obvious to too many that not everybody was profiting equally or fairly from post-war capitalist conservatism), to be followed, in the 1960s, by new ‘fringe’ academic literature on education. This fringe activity, as it turned out, became something of an avalanche from America, and a less dramatic outpouring from Britain. Books by authors such as Neill, Illich, Reimer, Holt, Goodman, Kozol, Postman, Weingartner, Pateman and Jules Henry, among others were produced mainly by Penguin Books and Pluto Press, and began to appear in bookshops and consequently in students’ backpacks – although less commonly on established lecturers’ bookshelves. For some, it was exciting stuff – at first.

These books seemed to speak directly to the painful experience many teachers were suffering daily. Postman and Weingartner advised teachers to stop blindly following the curriculum and become ‘crap detectors.’ A. S. Neill declared that schools should be based not on power and knowledge, but on love, given that ‘only love can save the world.’ John Holt exposed pupils’ survival methods (How Children Learn), detailed the mismatch between school ideals and the world of work which awaited its graduates (How Children Fail), and concluded that we go ‘beyond freedom’ (Freedom and Beyond). Ivan Illich and Everett Reimer pushed a deschooling agenda, and Paul Goodman labelled schooling ‘compulsory miseducation’ in his addition to the literature.

It was all exciting stuff. It mattered little that teachers had no control over the curriculum, no matter how much crap they detected; that even fixed desks made it rather hard to pursue the freedom and love supposedly in Neill’s school; that de-schooling was a ridiculous idea and an impossible goal; that detailing the utilitarian socialising nature of schooling did nothing to improve things and probably made teachers feel more guilty than before; that going beyond freedom was as empirically absurd as going over the rainbow; or that calling what happened in schools ‘miseducation’ still didn’t change anything.

What was clearly missing, to some, was the ‘why’ of it all, and how it had come to this and why we hadn’t seen it earlier, given that it seemed to have been staring us in the face for so long. But the search for answers was subverted by the sheer energy and brevity of these books. Most were such easy reads. You could pick them up, get started, get very excited and, as they were all very short and eschewed long words and technical terms, you could be finished with each in one reading and be discussing them with your mates the next day. And that, to a wide extent, is what happened. They were ‘user-friendly,’ and confirmed many academics’, including Ken Johnston’s, and many more teachers’ private convictions.

What was missing from all of this – and I have deliberately left out Freire who, for the quick theory-avoidance reader offered little more than the ‘banking concept of education’ – was both rigour and some underlying theoretical basis that added ontological and epistemological credence to the accounts and took them beyond the ‘Gee, right on, that’s how I feel’ level to one of reasoned justification. Enter the philosopher of education.

The timing could not have been better. Philosophers had, of course, long held a passing interest in education, and the John Dewey Society (ostensibly philosophers of education) had been running in the USA since 1935 (producing, I would argue, largely the aforementioned supportive rhetoric), but, at much the same time as the Penguin Education Specials hit the market, Philosophy of Education Societies had been formed in Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand. A new breed of academic was now at hand to apply a new discipline to the burgeoning literature – and the literature was found wanting. Thus, those new-fangled philosophers of education who did not want to indulge in either traditional supportive rhetoric or the new ‘radical’ polemics needed a different research program and were looking for it just at the time when Marxism was enjoying a welcome resurgence in much of Europe. But, as noted above, Marxism alone did not supply the necessary details, such that these philosophers of education were drawn to both the commentaries and to Neo-Marxism, the latter which led some of them to Althusser … and the vaunted Althusser study groups.

These groups, which were often ridiculed as the domain of ‘geeks’ and residents of ivory towers, put in the hard yards and the extensive study required of philosophers, and the most common and most distinctive thing that came out of them was the attention to Althusser’s ISAs. That hardly needs rehearsing now: what remains to be considered is whether this focus led to a justifiable revelation or an ongoing nightmare.

That matter was fully delved into, quite early in the piece, by Jim Walker, in a 12,000-word paper scathing of Althusser (and my work), which Walker himself recognizes to be far less than a full examination. With a tenth of the words left at my disposal in this ‘Opinion Piece,’ I warn the reader that what follows is little more than a sketch. With that said, let me consider first what went wrong for Althusser.

To begin with, Marx had given him what turned out to be an awkward steer in that Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, where he wrote:

the distinction should always be made between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the … ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out.

That, and similar phraseology that is commonly found throughout Marx’s works, sets out a theory with two ‘forms’ of knowledge, the scientific and the ideological. Althusser the Marxist has little philosophical choice other than to accept that: his problems are first to reconcile it with the baggage that he carries from Bachelard, and, given that he is going to discuss ideology, to clearly differentiate ideology from science. Althusser fails in both regards.

The influence of Bachelard, among other lesser things, leads Althusser into messy and often improbable tangles as he pursues the task of finding the solution to the ‘two types of knowledge problem’ in a search for an epistemological break in Marx’s development, and, when he ‘finds’ it, he absurdly declares a large part of Marxism to be ‘non-Marxist.’ The search provided a fruitless and unhelpful footnote to Marxist scholarship (intellectual masochists can begin with Reading Capital). But, unfortunately, it does affect the later work and – as philosophers we must not fudge or avoid it – the ISA essay.

Note that that essay is titled ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses’: it is as much an examination of ‘ideology’ as it is of the State Apparatuses, but is it an ideological examination or a scientific one? I will let the question go unanswered for the moment, noting only that Althusser attempts to distinguish ‘ideology’ from science and, in the process, gets into a serious mess. And so too do those who have followed him too closely, as I learnt to my detriment and embarrassment when critics began picking apart that part of my Education and Knowledge.

The second aspect of Marx that Althusser sought to tangle with is another common theme which we can highlight through snippets from Marx’s The Holy Family:

the emancipation of the working class must be the work of the working class itself.

and:

History does nothing.… It is man, real living man, who does all that, who possesses and fights; ‘history’ is not a person apart, using man as a means for its own particular aims; history is nothing but the activity of man pursuing his aims.

To put that another way, don’t reify ‘history.’ And, to combine the two points and re-phrase a quotation both Neilsen and I used earlier: real live people make history, and the emancipation of the working class must be the work of real living people.

The problem here for Althusser is that these real live people are subjects, and his epistemology will not allow for subjects or subjects of knowledge. Thus, as the ISA essay proceeds, we find ‘ideology’ strangely and consistently reified to the level of the subject (e.g. ‘ideology never says “I am ideological”’) and real live people positioned as agents of ideology and, more commonly, bearers of ideology.

Clearly, the place of human agency is both confused and seriously lessened. Althusser does, thankfully but in a somewhat contradictory way, recognize human agency, stressing that ‘schools are the sites and stake of struggle,’ and he both ‘asks the pardon of those teachers who, in dreadful conditions, attempt to turn the few weapons they can find in the history and learning they ‘teach’ against the ideology, the system and the practices in which they are trapped,’ and further, praises them:

They are a kind of hero. But they are rare and how many (the majority) do not even begin to suspect the ‘work’ the system (which is bigger than they are and crushes them) forces them to do, or worse, put all their heart and ingenuity into performing it with the greatest possible conscientiousness…. So little do they suspect it that their own devotion contributes to the maintenance and nourishment of the ideological representation of the school….

This recognition and praise for the ‘subject’ – a welcome inconsistency but an inconsistency no less – at least indicates the possibility of the existence of emancipatory working-class teachers, and it seems to have become lost or conveniently overlooked by those offended by the seemingly overall reduction of the working class to social sponges. It thus became easy, too easy, for the non-philosopher to instantly pounce with over-generalisations, misunderstandings and vagueness, all of which are found rolled up together in this short piece from Paul Willis’s cult book, Learning to Labour, endlessly and triumphantly quoted by the resistance theorists, anti-theorists, the ‘gut-feeling’ school of sociology and allegedly theory-neutral ethnographers:

Social agents are not passive bearers of ideology, but active appropriators who reproduce existing structures only through struggle, contestation and a partial penetration of those structures.

So, where does this leave philosophers of education with regard to Althusser? What ‘positives’ can we take from him?

For a quick start, the philosopher of education can apply the same blowtorch to Willis’s book, and those of its admirers, and quite easily show how that account, while again user-friendly, is muddled through lack of rigour and absurdly compromised through identification with its subjects, and, in the end, is hardly a serious rebuff to Althusser. After all, its subtitle is ‘How working-class kids get working-class jobs.’ And if that isn’t ‘reproduction of the relations of production,’ what is? In fact, what the book does show, as Willis follows his mentor E. P. Thompson’s direction to submit Marxist theory to ‘empirical impregnation,’ and perhaps more clearly than Althusser demonstrates, is that the relations of production were being just as neatly reproduced beneath the messy resistance that Willis saw as characterizing school and society.

Another means open to a philosophical approach to Althusser is a simple linguistic turn. Therborn was one among many writing soon after Althusser who described classes as ‘agents or “supports” of the relations of production within the process of social reproduction and change.’ It is of interest to revisit the ISA essay and in the process replace Althusser’s reifications of ‘Ideology’ and its ‘bearers’ with this linguistic turn: I venture that little is lost other than Althusser’s ‘purity’ and an unnecessary homage to Bachelard.

But one does not fix a broken theory, either with ad hoc replacements or by showing that one of its main opponents is far worse. What we can recognize is that, while the ISA essay may have its theoretic problems, it is not alone there. In the context of never yet having been faced with an incontestable essay, a pure theory or the absolute truth, I am happy both to hold to my previous argument and to re-assert that Althusser’s is the best going account we have of the reproduction of the relations, including ideological relations, of capitalist society. In providing such an account, Althusser has superseded so many of the commonly accepted theories of his time concerning the place of the working class in society along with their relatively meek acceptance of that place. These include naïve ‘capitalist conspiracy’ theory, Freudian ‘defence mechanism’ theory, Sartre’s strangely idealist ‘bad faith,’ standard twentieth-century ‘social learning theory,’ and naturalist theories of the inherent dumbness and laziness of the working class.

Had Althusser given us that, and that alone, I would be content. However, along with all of that comes another very significant gift: the illusion/allusion tool which enables us to identify and recognize how allusions to specific real cases can mask real large-scale illusions regarding social practices and relations. And two further points can be added.

First, Althusser may well have done enough to provide sufficient justification not only to blunt the edge but also encourage serious examination of the neoliberalism that was fomenting at the time that he published. And, second, in a somewhat dialectical fashion, there is value in identifying and then weighing up the value of searching out what fell between the cracks in Althusser’s theory. For instance, how do the Marxes, Althussers and Bachelards become critical subjects within the social relations of capitalist production, and what are the roles of different intellectuals in the great historical movement that is class struggle? Gramsci is accessible now: French translations of the Prison Notebookswere not readily available when Althusser was a student or author of the works considered here, nor were English translations around when I was first studying Marxism.

To conclude: Marxism is a programme, theory – call it what you like – as long as it is recognized to be vital and adapting as history-as-class-struggle continues and develops towards universal equity and dignity. It will be read, reread, reinterpreted and reformulated as historical conditions themselves are made and changed by human agency. In this long, historical, dialectical process Marxists of any age would do well to be aware of how Marxism has come to them – Marxists too make Marxism ‘under circumstances directly found, given and transmitted from the past.’ This applies equally to Neilsen as philosopher and me as philosopher of education. Yes, we must re-read Marx, but philosophers of education must also re-read Marx and neo-Marxist works on education and, in doing so, they will find both problems and potential solutions in Althusser. Ignoring that moment in history is dangerous folly. Engaging with it philosophically will be hindered by no greater overhanging spectre than the continuing presence of past and current versions of capitalist liberalism.

See Neilson, D. (2021). Reading Marx again. Educational Philosophy and Theory. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.1906648