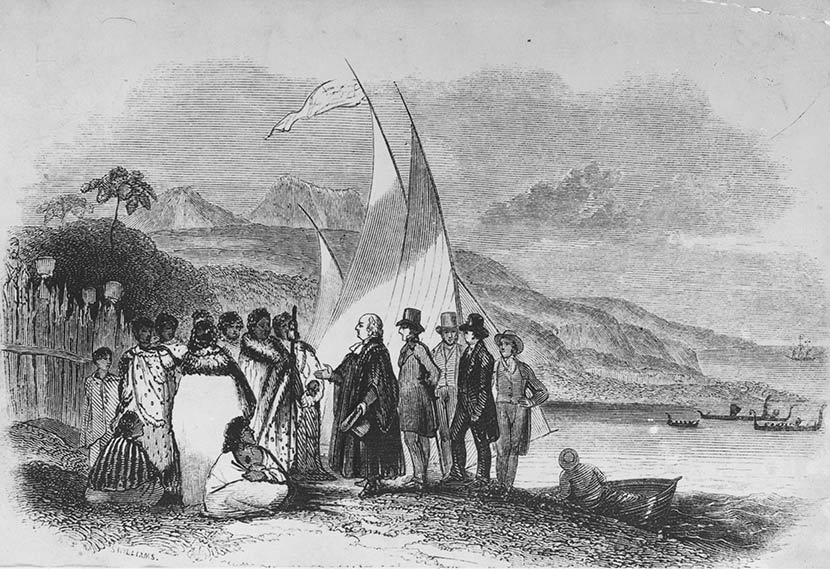

Samuel Marsden [meets Ruatara outside his pā (village) at] Rangihoua, 1814 (Te Ara)*

The translation of meanings between languages and cultures is an ancient point of contention. A defining feature of Aotearoa-New Zealand is the language binary of English and te reo Māori (the Māori language), which is important in national history and has been legally protected since 1987. Internationally, the movement to revitalise te reo Māori is seen as one of the most successful of all endangered languages. As languages, Māori and English work in very different ways, making te reo Māori difficult for the typical monoglot English adult to learn. Language issues like bilingual signage and saying a karakia (prayer) to open and close all meetings are very current for educators in all sectors of this country in 2024.

Translation is a knotty issue for language revitalisation: seductive in its power and simplicity, but potentially causing untold damage to the Indigenous language and culture involved – Māori, in this case. Translation has been used as a tool of Māori colonisation since Pākehā first arrived in Aotearoa. For example, copies of te reo Māori scriptures were printed in Australia and shipped to Aotearoa as early as 1827. Then, Anglican missionaries mainly worked in the north, especially the thickly-populated Bay of Islands among Ngāpuhi (the large tribal kin group covering Northland). The translation and printing of reo Māori Bible excerpts at that early date shows remarkable prescience of key concepts in sociolinguistics and intercultural education. Relatedly, the first school in New Zealand was opened in Rangihoua, Bay of Islands, by the Anglican Church in 1816, to teach Māori to read and write in te reo.

The issue is how cultural difference is perceived: as an advantage, a deficit or neither? In 2024, in Aotearoa-New Zealand, several generations of every Māori family have lived completely under European material conditions. Today, many Māori individuals, seemingly including two of the three co-leaders in the governing coalition in Aotearoa-New Zealand, have no better understanding than their non-Māori peers of the traditional Māori concepts and philosophies. Winston Peters is of the Ngāti Wai and Ngāti Hine peoples of the east coast of Northland, and David Seymour’s mother is from Ngāti Rēhia, another well-known hapū (sub-group) of Ngāpuhi.

In science, which struggles to connect with things Māori, translation seems to offer a uniquely powerful solution. The school sector is still using translated NCEA Science examination papers, and some in universities are toying with a wholesale translation of science texts to cross the intellectual Rubicon between science and te ao Māori (the Māori world). But translating science into te reo Māori inevitably creates neologistic forms of te reo, which are very different from traditional Māori language. I call it ‘neologistic’ because it is thick with neologisms (newly-lexed Māori words equated to items of science vocabulary) and forced into unnatural rhythms by the scientific syntax. Neologistic te reo (such as translated science text) damages Māori philosophy by setting Māori words adrift from Māori thought.

Here, I will consider ‘translation’ between English and Māori as it applies not only to words or sentence structures but also to value concepts and proverbial sayings picked up by the mainstream education system, including schools and universities. It is a philosophically rich topic, of which this column only scratches the surface. It is a suitable topic to tackle using my delineation of Māori philosophy as a Kaupapa Māori approach to investigating Māori knowledge. I will look in turn at four examples: he waka eke noa; whakapapa; ako; kaitiakitanga. Since language is itself a kind of metaphor for the world, it is not surprising that metaphor can lead us astray when we translate philosophical meanings between cultural languages as different as Māori and English. I call this confusion a ‘metaphoric philosophy’ arising in the intercultural space.

He waka eke noa

This simple four-word phrase has become known as a whakataukī (proverb), meaning something like ‘We’re all in this together’ or ‘There’s room aboard for everyone’ – but these notions distort its original Māori meaning. In pre-European days, Māori villages were often beside a river or bay. One or two small waka (canoes) made from local trees would be left at the point of coming and going in each village. These waka could be used by anyone who needed to cross to the other side, hence being known as ‘eke noa’ best translated in this usage as ‘for anyone to use.’ The extrapolation to mean ‘we are all on the same waka,’ while semantically close to the original, is annoyingly inauthentic; hence, it is my first example of Māori words or concepts taken up in distorted form into mainstream national educational discourses in Aotearoa-New Zealand.

Whakapapa

This concept is so central to Māori thinking that I have dubbed it the keystone or ‘master’ concept of Māori philosophy. I feel saddened when I hear it being cheapened as something derived from European/non-Māori cultures and meanings. On those occasions, the ‘whakapapa’ of something – a document, a group, an initiative – is being taken to mean its history, not only a chronology but also a narrative of coming-into-being. It is an extrapolation of the real meaning of ‘whakapapa’ that I find acceptable as a figure of speech for a Māori to use but offensive when used by Pākehā who clearly have no idea of, nor interest in, the authentic Indigenous concept of whakapapa in Māori philosophy.

Ako

This word probably takes top prize as the most distorted Māori concept to be picked up and given new meaning by national schooling and education systems. ‘Ako’ acts as a cognition-related verb that can mean either to teach or to learn; in context, the sentence tells the listener which meaning is being invoked in each usage. The related word ‘whakaako’ made by adding the causative prefix ‘whaka-’ to ‘ako’ is generally taken to mean ‘to teach’ (to make to learn). Ako is not the only cognition-related Māori verb that can mean both of two opposite meanings, another being ‘mahara,’ which can mean either to remember or to forget, while ‘whakamahara’ means to remind.

The distorted version of ‘ako’ found in education discourses is taken as meaning ‘to learn and to teach at the same time’ or ‘both-ways’ teaching and learning as if te reo Māori were incapable of distinguishing between the two processes. As with the above examples, its distorted meaning is semantically close but conceptually distant from the more interesting authentic set of meanings of ako. These examples fit the worrying trend noted above of setting Māori words adrift from Māori thought.

Kaitiakitanga

This word has come to be equated with the English concept of ‘conservation of nature,’ but careful consideration reveals it to be another distortion of Māori philosophy. Its use in this now-dominant sense can be traced back to 1992 and a key paper written for the Ministry of the Environment by Māori Marsden and Te Aroha Henare, ‘Kaitiakitanga: A Definitive Introduction to the Holistic World View of the Māori.’ Marsden and Henare took the traditional concept of ‘kaitiakitanga,’ which originally referred to being under the protection of ngā atua (the Indigenous gods), as a Māori metaphor for the notion of conservation of nature. This paper had a significant influence on including Māori concepts in environmental policy, but, in the process, the original meaning of kaitiakitanga was obscured. Marsden well knew the original Māori meanings of the concepts he used in his English-language essays and would have been fully aware that he was extrapolating the meaning of kaitiakitanga as a metaphor for the conservation of nature, but the distinction has subsequently been lost.

Whether we are translating Indigenous concepts into a global language such as English or translating Indigenous practices into novel contexts in our universities, it pays to remain cognisant of the difference and danger of reducing rich webs of meaning to convenient metaphors. There is more work to be done on the topic of metaphor in the translation of culture.

* Reverend Samuel Marsden stands on the beach in his black clerical clothing in this drawing that imagines his 1814 encounter with Ngāpuhi rangatira (leader) Ruatara outside his pā at Rangihoua, near Te Puna, in the Bay of Islands. Behind Marsden are the missionaries that he would leave to set up the first Anglican mission station in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Ruatara had met Marsden on a whaler and invited him to visit, having assumed the role of protector and patron of Marsden as ‘his Pākehā.’