Dedication

As an “intellectual in emigration,” Theodor Adorno wrote Mimima Moralia, his book of philosophical, sociological, cultural, and psychological reflections “from the standpoint of subjective experience, [which] means that the pieces do not entirely measure up to the philosophy, of which they are nevertheless a part.” I have always been fascinated by this book. As form follows function, he uses common aphorisms as a springboard for this particular advance of critical theory; each section is a short but deep dialectical dive through the essence of the experiences about which he ruminates. As an intellectual in quarantine away from my home for most of the last year, I feel some loose kinship to Adorno’s condition of displacement and found the form compelling as well as comforting. I am protected yet also partially blinded by my shelter.

Nothing is harmless anymore. –Theodor Adorno

1

You never forget how to ride a bike. Journalist Gabriella Borter writes, “Hospitals and morgues in [New York City] are struggling to treat the desperately ill and bury the dead. Crematories have extended their hours and burned bodies into the night, with corpses piling up so quickly that city officials were looking elsewhere in the state for temporary interment sites.” My nine-year-old daughter, on this same day, in a town about eighty-five miles from the crematories and refrigerated temporary morgues, learns to ride her bike. A northwest wind rips open several days of raw rain, ushering in chilly spring air, cerulean sky, and bursts of Goldenrod along the harbor’s edge. It takes just a short jog and gentle push from me to send her off into that magical moment in which velocity, gravity and centrifugal force propel her beyond my reach. Her triumphant laughter is stolen by the wind as she pedals her bike farther and farther away from me.

2

Fly like a butterfly, sting like a bee. Often referenced as the shortest poem ever written, Muhammad Ali’s poem “Me, We!” captures in the most succinct way the challenges that the coronavirus pandemic presents to a species not quite ready for primetime. According to George Plimpton in the film, When We Were Kings, after Ali completed his commencement address to Harvard’s graduating class of ‘75, a student yelled out from the audience, “Give us a poem!” I imagine “The Greatest” looking out from the podium over the congregation of overwhelmingly White faces and spreading his famously long arms as if getting ready to accept the love of a grateful child. His grin widens: “Me, We!” A stinging jab, followed by a powerful overhand right.

3

History is circular yet non-repeating. It should come as no surprise that authoritarian-minded leaders throughout the world see the pandemic as an excuse to undermine democratic systems and institutions, thereby consolidating their grip on power. Uniquely 21st-century fascistic regimes are growing roots throughout the world. Ultra-nationalistic, racist, xenophobic, exploitative to labor, and hostile to women, Jews, and gay people, these newly emerging authoritarian systems are using the current emergency situation to rationalize what the oppressed have always known; instability and fear seed the authoritarian imagination while the promise of comfort and salvation quells dissent. “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a concept of history that corresponds to this. Then, it will become clear that the task before us is the introduction of a real state of emergency; and our position in the struggle against Fascism will thereby improve.” The authoritarian imagination sees public troubles as opportunities for the consolidation of private power. This is the real state of emergency of which Benjamin cogently warns; hidden behind the rush to save lives–lives that were considered, just weeks ago–not worth saving, is the rush to power. Let’s be diligent when writing the history of yet another “emergency situation”; our conception of history must align with the insight that the real emergency in our time is neoliberal fascism, a rise in authoritarian-minded leadership, a collapse of democracy, and the delegitimization of truth.

4

Rise and Shine. In the children’s animated film, Up, the three-minute chronological montage of Ellie and Carl’s loving life together up until her death is poignant, beautiful and sad because it is everything we can hope for and two and half-minutes more than most of us will ever remember.

5

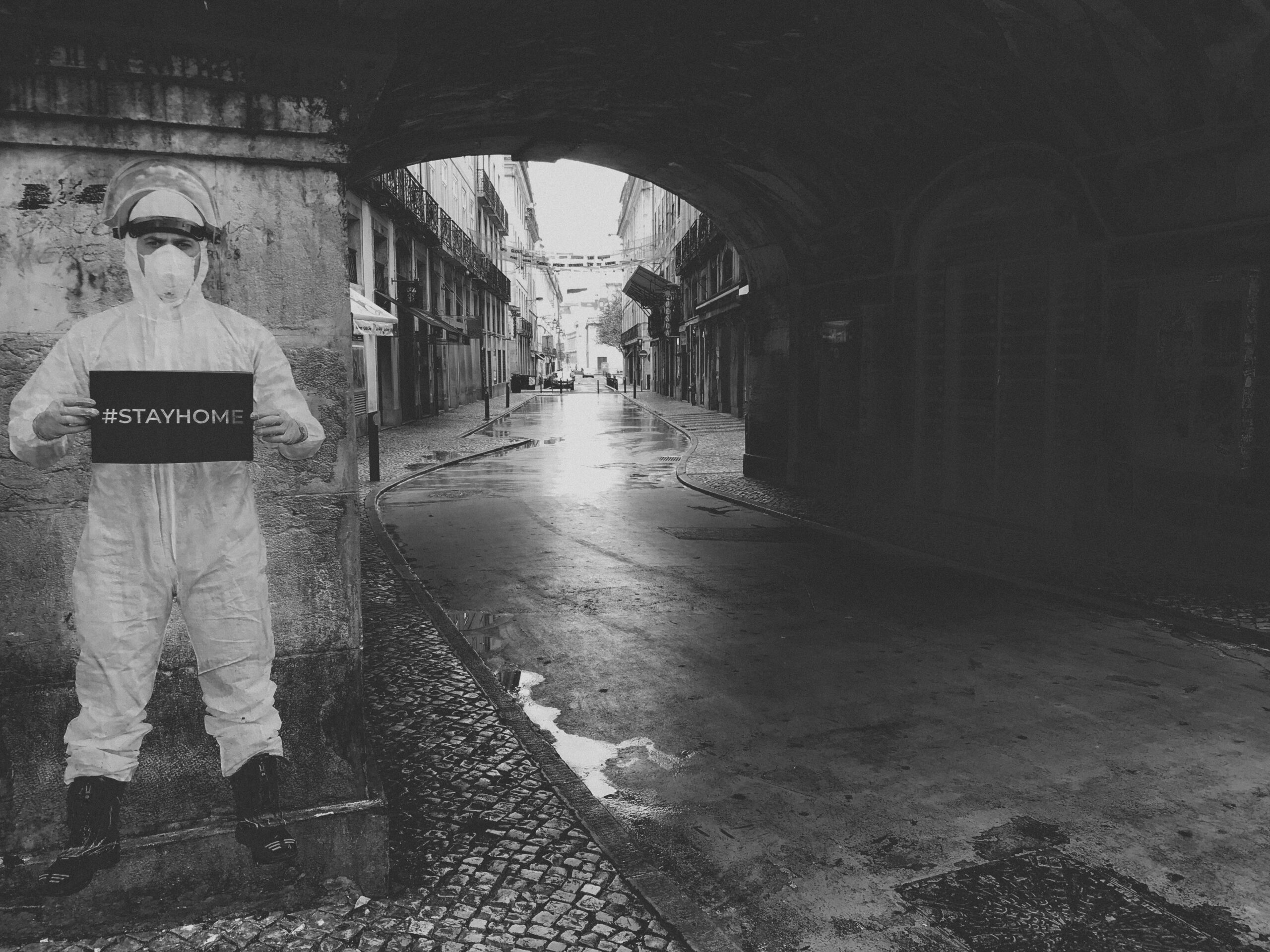

Eyes wide shut. Masking the face has a long history as a theatrical device, a medical wonder, religious garb, an accoutrement of all kinds of criminal activity, protection against blowing sand and debris, a shield against smog and bugs, a costume, a sign of sexual deviance, and a symbol of terror. Not unlike the hood, the meaning of a face mask changes not only with its application, but who is wearing it. Whose eyes peer out from above the mask? What race, ethnicity, sex, religion, and/or nationality do we recognize behind the mask? By the color of skin and roundness of eyes, we guess at the shape of the mouth, the fullness of lips, the length and broadness of the nose. We search for other signs that might help us learn if the masked person is a friend or an enemy. When our face is masked, our identities become a blank slate upon which others write their fantasies, pleasures, terrors, fears, and hopes. When you want to know if someone is lying, look at their mouth rather than their eyes. It is true that pupils dilate under certain circumstances, saying yes when everything else indicates a no or vice-versa. Yet, more often than not, eyes easily hide what’s lurking in the heart and mind; the mouth gives it away almost every time. Cover it up and we are uncertain about a person’s intentions; our intuition is short-circuited. In an effort to get our footing, we revert back to tribal knowledges, biases bread in the bone of memory and mother tongues; driven by fear or lust, we create flight or fight stories in which we live in a blink a lifetime with the masked protagonist. It is why some African-Americans refuse to wear face masks during the pandemic. Those who demand that everyone should wear a mask on the street, without acknowledging the risks of doing so for African-American males in particular, are tone-deaf to the serious threat and privileges of living within a White supremacist culture. Young Black men are criminalized for wearing a sweatshirt with the hood up; police and others have justified killing Black men for no more than wearing a hood at the wrong time and in the wrong place. What of the threat of violence or incarceration to Black men who wear a mask in the wrong place at the wrong time (which of course is every place at all times)? The savage inequities that African-American’s experience during their lives contribute to the inequality we are seeing in death. There is simply no way to separate White supremacy and the inequitable impact the disease is having on African-American communities. Whether it’s the danger of wearing a mask or the over-representation of African-American people in “essential” jobs, the question remains the same: Who is to protect them from those of us who will exploit their labor, criminalize their bodies, and/or pathologize their cultures, communities, languages, and histories while we demand that they help save us from ourselves?

6

The difference between poetry and rhetoric

is being ready to kill

yourself

instead of your children.

7

Woke up, fell out of bed. Dragged a comb across my head, found my way downstairs and drank a cup, and looking up I noticed I wasn’t late because I had nowhere to go. I didn’t need my coat or my hat, and it no longer mattered if I made the bus, subway, or train in seconds flat, so I made my way upstairs and had a smoke, turned on my computer just in time to make my first Zoom meeting of the day, and everybody starting speaking at once from inside their little Hollywood Squares; in the age of COVID-19, someone’s kid screamed, and I went into a dream. Chaos and uncertainty reign. Temporary refrigerated morgues line the streets as states outbid each other in the free-market for medicine and PPE. But did you actual see the bodies, the conspiracist asks? Some of us eat eggs, yogurt, fresh fruit, vegetables, steak, drink copious amounts of coffee in the morning and sip tequila or wine in the evening; others seethe from hunger and shelter in cramped places. Same as it ever was. We are all in this together, they say. Same as it ever was. We have always been together yet apart. I am he as you are he as you are me, and we are all together; see how they run like pigs from a gun, see how they fly; I’m crying.

8

Where there is no vision, the people perish. It is a brutal irony that those workers we now applaud from the windows and balconies of our apartments were, before the pandemic, the under-appreciated, under-class; the invisible workforce. So many of them were looked down upon, sneered at, the butt of jokes, poorly paid, constantly refused gratuities even after delivering whatever it was we were too lazy to go out and get ourselves; the loaders, packers, deliverers, and shoppers—those that allowed the few and the proud to do “real” work and earn “real” money. Those who were “disposable” are now “essential.”

9

The New Normal.

You may find yourself, living in a shotgun shack, and you may find yourself in another part of the world, and you may find yourself, behind the wheel of a large automobile, and you may find yourself in a beautiful house, with a beautiful wife, and you may ask yourself, well, How did I get here? And you may ask yourself, How do I work this? And you may ask yourself, Where is that large automobile? And you may tell yourself, This is not my beautiful house! And you may tell yourself, This is not my beautiful wife! You may ask yourself, What is that beautiful house? You may ask yourself, Where does that highway go to? And you may ask yourself, Am I right? Am I wrong? And you may say yourself, ‘My God! What have I done? (Brian Eno and the Talking Heads)

10

The art of the weak. Michel de Certeau makes an important distinction between tactics and strategies. For de Certeau, strategy is the architecture by which official power organizes its ideas. Tactics, in contrast, are the disruptive practices of the marginalized, of those that work and live within the architecture of power, yet are not served in part or in full by that architecture. I am thinking about Ani DiFranco’s lyric “Every tool is a weapon if you hold it right,” in comparison to Audre Lorde, who argues: “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” I always think of a pencil when I hear DiFranco sing this line. I can see Jason Bourne or John Wick turning the pencil into a weapon. But I also think about Paul Willis’s rebellious working-class lads fighting against a system whose reach turns rebellion on its head.

11

We sit in our sixth-grade desks with the blinds

closed against the tree-lined streets

as the letters of the world rise up

and, forming a single word,

eclipse our world and fill our mouths with shadows.

12

Hat in hand—September 11, 2001. Sitting in gridlock on route 3 in NJ, trying to get back to my apartment in Hoboken, I look over to see a Sikh man slowly, carefully unwrapping his dastār. The twin towers in downtown Manhattan collapsed hours before and we listened to the news reports on the radio, a cacophony of frightened, sad, and angry commentators constructing history from the incinerated bodies, melted steel, and gray ash on the southern tip of Manhattan. There was surely going to be hell to pay, but the fear circulating through the stalled traffic was generated from the realization that hell is what we were just paid, with many not understanding the debt. The Sikh looked straight ahead, fear and knowing in his eyes, trying to remove any mark that could be misinterpreted as a sign of complicity with whomever might have orchestrated such violence. The hair bristled on the back of my neck. I was terrified that people around me, scared, stuck and looking for revenge would pull the man from his car and rip his arms from his body, smash his face into the asphalt. I was afraid I would be compelled to intervene and suffer a similar fate. I was afraid I would do nothing and stand by and witness the violence done to an innocent man. With the unwrapping of his dastār complete, and his invisibility relatively, yet contingently secured, I relaxed the grip on the wheel and got out of my car to wonder with the other stuck motorists, what next?

13

The terror of the unforeseen. Riffing off of Philip Roth’s apt phrase that he uses in the Plot Against America to describe how “the science of history turns disaster into an epic,” Henry Giroux uses it as a point of departure for a cogent critical analysis of Trump specifically and what he calls the evolution of neoliberal fascism in the United States more generally. As the coronavirus pandemic lays waste to tens of thousands of people across the globe (and counting); as we shelter ourselves in small tribes against the viral winds; as poor children and families, already living on the edge of safety and security, try to survive with minimal school support coupled with community networks weakened by enforced social distancing; as neighbors, silhouetted against the shadow of sickness and death, morph into strangers, the phrase the terror of the unforeseen takes on a new meaning. Not quite a manifestation of political, cultural or social power, viruses hide beneath our flesh, in our blood, hide in our saliva; the circulated images of the novel COVID-19 virus are the stuff of alien nightmares, invaders infiltrating the human ecosystem, attaching to major organs, killing some, causing relatively mild symptoms in others, while using some of us like so many Trojan horses. The terror of the unforeseen, under the regime of COVID-19 is twofold. First, it is the invisibility of the virus as it enters our system undetected; we are terrorized by what we can’t see but can harm us. Second, as we help it spread, “live,” and thrive, we become strangers to each other; never knowing who might be a viral host. Community becomes a dangerous crowd; atomization and militarization our only retreat.

14

Those who can’t do, teach. Beth Lewis from ThoughtCo explains that a “teachable moment is an unplanned opportunity that arises…where a teacher has a chance to offer insight to his or her students. A teachable moment is not something that you can plan for; rather, it is a fleeting opportunity that must be sensed and seized by the teacher.” While some teachers I know think about teachable moments as positive and important because they arise out of a learner’s intrinsic need to know and understand, others are not as enthusiastic. Because teachable moments oftentimes require educators to digress from their planned lessons and standardized curriculum, these teachers “refuse” to sense and seize on them when they arise in their classrooms. The reasons for their “refusal” are many and understandable. Standardized testing forces teachers to teach to the test. Scripted pedagogies force teachers to follow a “scientifically proven” program that is guaranteed to work. Narrowly conceived state curriculum standards deemphasize local knowledge and experience in the classroom. “Value-added” assessments of teachers link student performance on standardized tests to teacher evaluations which makes teaching to the test a rational irrationality. Panoptic surveillance of students and teachers in the classrooms control student and teacher behavior by creating a “chilling” pedagogical atmosphere in which everyone is afraid to say or do anything that could be classified as controversial or inappropriate. More generally, the damaged nature of the sociopolitical-cultural climate outside of school creates an environment within the school in which teachers and students are afraid to take-up important issues because they want to avoid conflict and/or fear being marked as politically biased.

15

The Homeless Erasure. As a class of third-grade students sketched the architectural details on a church across the street from their school as part of a general lesson plan about religion and sacred spaces, a few of the students asked about the homeless man who was sleeping on the steps of the church. The teacher, a fifty-year veteran teacher, told them to not include the man in their drawing and to pay attention to the stained glass, spires, ornate doorway, curving stairway (upon which the man lay), and the stone archways. What makes this “refusal” even more spectacular is the fact that the school is a “progressive” Quaker institution with a mission to educate students about social injustice. They even run a shelter in the school in the evenings and the students regularly work with food pantries to assist in helping people who can’t afford to buy enough food to eat. Even within this context, the teacher couldn’t/wouldn’t sense and seize upon this teachable moment. Whether she sensed it and then refused to address it or whether she didn’t see it as a teachable moment and therefore couldn’t seize it, I do not know. The end result is the same. By ignoring this teachable moment, the students learned that the homeless man and the conditions of homelessness more generally were less important to their education than the architecture of the church. By ignoring this teachable moment, the teacher missed the opportunity to address the issue of homelessness and the role of religion and education in both serving the needs of the poor as well as normalizing the experience of homelessness.

16

There’s a sucker born every day. As a spectacle, Trumpism consumed all attempts to distinguish representation from reality, making the act of discrimination just another representation no more real than the representation it was trying to make visible. Guy Debord (1967) writes, “The basically tautological character of the spectacle flows from the simple fact that its means are simultaneously its ends. It is the sun which never sets over the empire of modern passivity. It covers the entire surface of the world and bathes endlessly in its own glory.” As part of the spectacle of Trumpism, Trump was simply and dangerously a darkening representation of power that shifted and pivoted fluidly because reality was negated within the spectacle. “The spectacle is ideology par excellence, because it exposes and manifests in its fullness the essence of all ideological systems: the impoverishment, servitude and negation of real life.”

17

The end is near. Adorno writes in Minima Moralia, “The more passionately thought seals itself off from its conditional being for the sake of what is unconditional, the more unconsciously, and thereby catastrophically, it falls into the world. It must comprehend even its own impossibility for the sake of possibility.” We enable thoughts and knowledge itself by considering the possibility that both are impossible. By doing so we can reclaim a degree of sanity in times that are, by most standards of measurement, insane. Whether there is redemption at the end of the tunnel, as Adorno says, is “inconsequential.” But I hope there is, because I am pretty sure there will be hell to pay.