The next pandemic will erupt, not from the jungle, but from the disease factories of hospitals, refugee camps and cities. (Wendy Orent, 2014)

Covid-19 marks the return of a very old – and familiar – enemy. Throughout history, nothing has killed more human beings than the viruses, bacteria and parasites that cause disease. Not natural disasters like earthquakes or volcanoes. Not war – not even close. (Bryan Walsh, 2020)

Evolutionary Biology and the Social History of Viruses

Evolutionary Biology and the Social History of Viruses

In evolutionary biology there is a strong hypothesis that holds that viruses may have been free-living organisms that as parasites were the precursors of life. Their diversity runs into trillions and unlike all other biological organisms some have RNA genomes and some have DNA genomes; some are single-stranded and other are double-stranded genomes; they can only self-replicate within a host cell; and, none contain ribosomes and therefore cannot make proteins. Among the three main theories of where they came from and whether they are alive, the 2005 account by Eugene Koonin and William Martin holds that viruses either predate bacteria, archaea, or eukaryotes or coevolved with host cells, but while they can evolve rapidly because of their short generation times and large population sizes, viruses cannot reproduce by themselves as noted in Nature, 2020.

The social history of viruses and their impact on the human species began during our evolution and epidemics have been record as early as Neolithic times when human beings began to lead sedentary lives in relatively densely settled agricultural communities with domesticated plants and animals some 12,000 years ago. Smallpox and measles are among the very earliest of viruses that affected human beings. Influenza pandemics have been recorded as early as 1580 when Spanish colonial conquests began in South America decimating the indigenous peoples. The 1918-19 influenza epidemic killed an estimated 50 million people world-wide and it was not until the 1930s that the science of virology was established with the invention of the electron microscope and immunology and vaccination developed.

Philosophy & Literature of Viruses, and an Ethics of Care

There is a literature and philosophy of viruses, of the plague, the epidemic and the pandemic. Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, published in 1722 tells of one man’s experiences during the Great Plague of London in 1665. More recently Albert Camus’ The Plague is a classic example of the existential philosophical novel. Camus’ attitude is that, in a world without meaning, the plague provides a moral opportunity for people to find themselves in the struggle of sacrifice for the greater good: ‘What’s true of all the evils in the world is true of plague as well. It helps men [sic] to rise above themselves’ (Camus, 1991, p. 125).

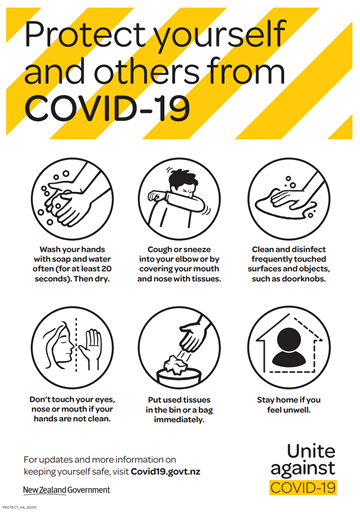

The philosophy of pandemic is truly a philosophy for all peoples. It reflects not only the human significance of pestilence and plague, or the rise of modern viruses like Covid-19 that demonstrate the transition across species but also themes of individual/community: self-interest and collective responsibility, the sacrifice of first-contact health workers, the ethics of care for the other. It has become apparent that the main practices that we can use to deal with a virus like Covid-19, with no specific drugs or treatment available to counter it, nor any vaccine as yet, have meant that we have had to revert to ages old practices of isolation, quarantine, personal protective equipment and stringent hygiene practices but also use the internet resources and apps for information, health updates, contact tracing, to work from home and of course for social connections and so on. The global shared open science was initiated in January 2020 when Chinese scientists, Ren and colleagues made the viral genome public in the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, as reported in the Asian Scientist Magazine. This acknowledges the enormous threat to public health and it was from this sharing of data which enabled the collaborative, collective approach to this crisis has overtaken the usual competition mode of medical sciences research. The science research focus on Covid-19 has been impressive as Matt Apuzzo and David Kirkpatrick noted in April 2020 in the New York Times

Normal imperatives like academic credit have been set aside. Online repositories make studies available months ahead of journals. Researchers have identified and shared hundreds of viral genome sequences. More than 200 clinical trials have been launched, bringing together hospitals and laboratories around the globe.

The philosophy of viruses and pandemics is often conceived of as an ethics of self-isolation and of the human effects of social isolation. It also has the problem of community breeches, the siege mentality and the problem of the ‘free-rider’. But it is simultaneously about care of the self and care of others, as we become increasingly aware of our interconnectedness on multiple levels in our contemporary world.

‘Viral Modernity’ and Post-Truth

The 2018 book, Post-truth and Fake News, edited by Michael Peters, Sharon Rider, Mats Hyvönen, and Tina Besley, provided an examination of the ‘post-truth’ era in relation to the concept of ‘viral modernity’. In a 2020 article with international colleagues, Michael A. Peters, Petar Jandrić & Peter McLaren, extended the notion in two main ways. First, by reference to epidemics, infodemics, and the bioinformational paradigm, we argue that ‘viral modernity is a concept based upon the nature of viruses, the ancient and critical role they play in evolution and culture, and the basic application to understanding the role of information and forms of bioinformation in the social world’. Second, through the development of ‘A Theory of Post-Truth’, a notion of semiotic systems inspired by Gregory Bateson’s remark in his 1972 Steps to an Ecology of Mind ‘There is an ecology of bad ideas, just as there is an ecology of weeds, and it is characteristic of the system that basic error propagates itself’ (p. 492). We note:

The application of the viral concept thus draws on a parallel between viral biology and information science – the ‘bioinformational’ paradigm – that brings together two of the most powerful forces that now drive cultural evolution. In this paradigm one of the prime intellectual tasks is to understand the ‘epistemology of conspiracy’ because ‘viral politics’ has become ‘government by conspiracy.’

Viral forms of information – lies, misinformation, rumours, propaganda and conspiracies – do not meet the criteria of ‘justified true belief’ since there is no belief, truth or justification condition, and typically they may be politically motivated utilizing fear and panic that are highly damaging to the health of the public sphere. ‘Viral politics’ depend on viral media where truth is no longer considered to be an issue. It is replaced by the strength of subjective conviction, conspiracy that coincides with existing prejudices and is easily manipulated through Artificial Intelligence (AI) digital networks.

Pandemic Education

One thing that the Covid-19 pandemic brings home clearly is just how connected with are at the microbiological level – how we can pass on bits of our own biome, bacteria and viruses through sneezing, coughing and touch (Covid-19 reportedly can remain on hard surfaces such as plastic and stainless steel for 72 hours). Our physical microbiological contact is an expression of our biological interconnectivity which also has cultural, social and political dimensions that are played out through the means of a technological superstructure that takes many digital and postdigital forms. And while the ‘nets’ are a prevalent dominant cultural form, the electronic media that predates the internet has now provided human beings with a global interconnectivity – with lots of holes, darknets, and subterranean activity – that expresses itself in global markets, news and communication. These are the ways that the virtual and the digital echo and interact with the physical and the microbiological.

We are moving to a more enmeshed global interconnectivity but this is does not mean we are becoming one. Interconnectivity is a concept that emerged out of cybernetics, biology, ecology, and network theory. It points to the notion of non-linear dynamics that follows from the idea that all parts of a system interact with and rely on one another and that a system is difficult or sometimes impossible to analyze through its individual parts considered alone. Scientifically, the concept is closely linked to the observer effect and the butterfly effect where a small change in starting conditions can lead to vastly different outcomes. Understanding the butterfly effect can give us a new lens through which to view markets, social life and education.

The butterfly effect is often linked to the concepts of interconnectedness which is used to refer to the spiritual, and interdependence which relates to the moral realm. Pandemic education as a philosophy of education is therefore the philosophy of interconnectivity understood as a fundamental educational, epistemological, and ethical principle that refers to:

- educational interconnectivity (Open Education, Open Science)

- moral interdependence and the concept of humanity

- spiritual interconnectedness.

It refers also to 5th and 6th generation cybernetics in mathematical algebraic logic, algorithms, and automation control theory in the application to intelligent systems of digital technologies.

Cybernetic ethics views the evolution of ethical systems in terms of the informational feedback certain human actions generate.

After the Pandemic?

Pandemic Education is an opportunity to raise political, economic and ecological questions about the viral anti-globalization experiment, such as:

Politics

Which political system works best at quarantine and social isolation – American individualism or Chinese collectivism; democracy or one-party state; free-market or welfare state?

In neoliberal times how well do Westerners vs Chinese cooperate, obey the rules, become compliant and willingly work for the greater good?

What are the problems of the community ‘free-rider’, or those who do not follow newly established community norms of self-isolation?

What are the complexities of individual self-interest vs community that affect the public interest?

Ecological

What are the new relations between virus pandemic and sustainability practices?

What is the effect on climate change?

What is the effect on bio-diversity?

Science

Can the freedom of information including scientific communication and open science outrun viral self-replication?

How have governments interacted and interfaced with science including examples of suppression of information and forms of disinformation?

What have been the government/science relationship during this pandemic?

Information

What are the bioinformational cross-border flows that postdate the nation state?

To what extent can financialization and finance capitalism, whether state-led or market-led, be seen as part of the bioinformational paradigm?

To what extent has viral fake news, social media and conspiracy theory generated public and global damages and to what extent is this an aspect of contemporary biopolitics?

In the innovation race to invent an anti-Covid-19 vaccine where do the major advances come from and what organisations are well placed to make huge profits?

Economic

What are the consequences on the poor, on global inequalities?

What are the consequences of the lock down specific industries, in particular on mass tourism?

The consequences of lockdown on hospitality industries?

The co sequences on small business (less than10 employees)

The effect of increased unemployment in both the short and long-term?

Is mass consumerism sustainable? (do we really need all that stuff?)

Pandemic Education is also an opportunity to contextualise, to historicise and to raise questions about what happens both during and after the pandemic – personally, psychologically, locally and globally. Unless the spread of Covid-19 and the chain of transmission is broken it may well become endemic and seasonal like various flu viruses.

All industries that are based on travel or trade such as travel, tourist and international education industries will suffer in the short term with many enterprises going out of business, and, conversely local industries, especially those who source their materials locally, will possibly enjoy small-scale success. China is well placed to make a successful return to ‘normal’ and New Zealand needs to carefully consider its trade status with the global presence of China and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and especially its location with other countries in the ‘Asia-Pacific’ region. Investment in full digital systems and infrastructure, their integration with existing systems will mean the development of a set of new work, business and educational practices.