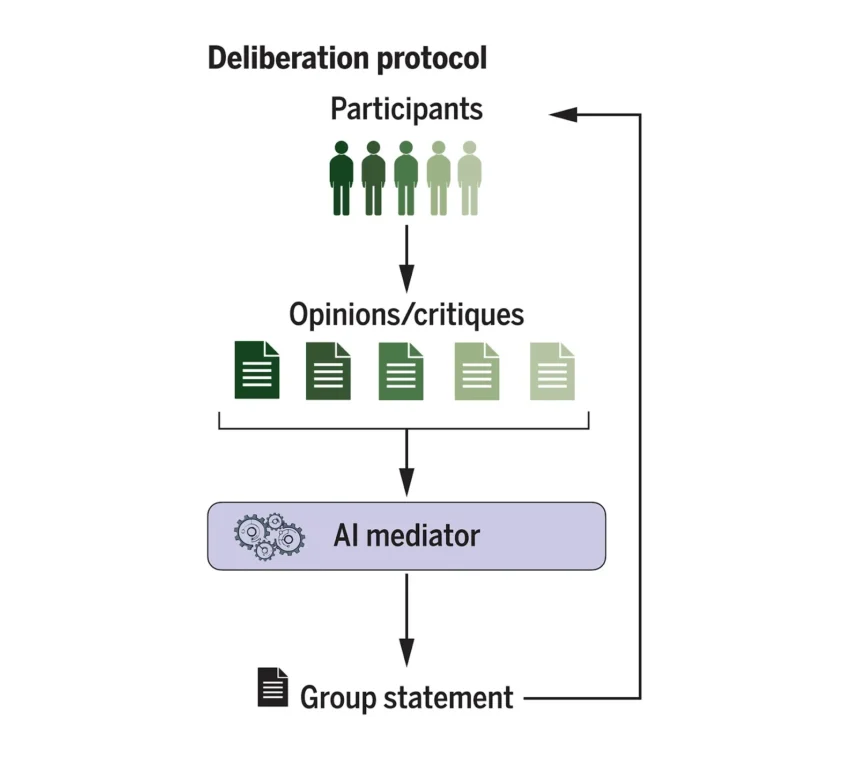

The Oxford/DeepMind ‘Habermas Machine’ (from Nicholas Kees at LessWrong)

The Oxford/DeepMind ‘Habermas Machine’ (from Nicholas Kees at LessWrong)

1. Introduction: The Promise and Problem of EdTech

EdTech has always been eager to help. It arrives at the educational scene armed with dashboards, integrations and the kind of cheerful rhetoric usually reserved for startup pitch decks and TED talks. It promises to support teachers, empower learners and ‘transform’ classrooms in much the same way one might transform a spreadsheet – through efficiency, automation and a decent Wi-Fi connection. What often goes unremarked is that this vision of education bears a striking resemblance to a logistics problem. And, like any good logistics system, it prefers things that move predictably, respond promptly and can be tracked in real-time without too many complications. Unfortunately for EdTech, education is famously uncooperative on all three counts.

What we call teaching is less a matter of control than of contingency. It involves relations with others who are inconveniently sentient, frequently resistant and often more interesting than the outcomes used to measure them. The most fundamental conditions of education – ambiguity, dialogue, resistance to closure – are not design flaws to be patched in the next update. They are what make education education. When EdTech platforms speak of enhancing learning, they usually mean enhancing what can be measured, sorted, or scaled. This has little to do with the actual work of meaning-making that happens in classrooms and even less to do with the slow and often messy business of becoming a subject among others.

The problem, then, is not simply that EdTech does a poor job of supporting education. That would at least suggest the possibility of improvement. The real issue is that the operational logic of EdTech is built on premises that are structurally indifferent to the kinds of practices education involves. It treats the interpretive complexity of pedagogy as a kind of workflow inefficiency. This is not because the people designing EdTech are malicious. On the contrary, most of them are quite sincere in their belief that they are making things better. That is precisely what makes the problem harder to see and harder to name.

To do that naming, I turn to Jürgen Habermas – not for his optimism about procedural reason, which has aged about as well as powdered wigs, but for his account of what happens when the legitimacy of a system begins to fray. A legitimation crisis, in Habermas’s view, occurs when an institution can no longer maintain the appearance that its actions match its stated purposes. It is not simply a failure of trust. It is a breakdown in the narrative a system tells about itself. This essay argues that EdTech’s contradictions – its professed support for education and its erosion of pedagogical conditions – should be understood in exactly these terms. The problem is not a lack of alignment but the systemic inability to make alignment possible under prevailing conditions.

What follows is not a manifesto against technology. It is an attempt to describe how education has come to be understood through a set of technical and managerial assumptions that render its most vital features unintelligible. If EdTech fails to support education, it is not because it is too new but because it is too familiar – too well-adjusted to a broader system of instrumental rationality that confuses predictability with insight and data with understanding. This is a crisis not of innovation but of meaning. And like all such crises, it presents an opportunity for rethinking the stories we tell about what education is and what we think it is for.

2. Contradiction, Crisis and the Question of Framework

The word ‘contradiction’ has acquired a rather dramatic reputation. It tends to summon visions of explosive tensions or deep philosophical impasses, as though one were being invited to witness a cage match between ontology and epistemology. But the kind of contradiction at issue here is altogether more banal, which is precisely what makes it so effective. It is not a cosmic clash of values nor an existential standoff at the heart of being. It is the sort of contradiction one finds in a job posting that demands both innovation and adherence to standard operating procedure. It is what happens when a system says one thing in public, does something else in practice and is so well-adjusted to the difference that no one thinks to mention it.

Jürgen Habermas is especially good at noticing this kind of thing. His account of the legitimation crisis is not exactly beach reading, but it does offer a useful guide to what happens when a system loses the ability to make its operations appear consistent with its stated purposes. This is not the same as hypocrisy, which at least presumes some awareness of the gap. A legitimation crisis is more like the moment a ventriloquist forgets which puppet is talking. The ideology no longer animates the machinery. The promises no longer match the procedures. The result is not a moral scandal but a slow erosion of credibility, the kind that sets in when institutions continue to function without anyone quite believing in them.

It may be tempting to interpret this crisis in more metaphysical terms. One might imagine, for example, that education is simply too haunted by contradiction to ever be reconciled with itself. Jacques Derrida would certainly have been sympathetic to such a view. His notion of aporia describes a kind of constitutive impasse in which the very conditions that make something possible also make it impossible. Jacques Derrida’s hospitality, for instance, can never be pure because the act of welcoming already establishes a threshold of exclusion. One could say the same of education, if one were so inclined. Teaching requires structure, and yet structure always risks foreclosing the openness it is meant to support.

But the contradiction we are dealing with in EdTech is of a different order. It is not metaphysical, and it is not inevitable. It is the result of a historical alignment between educational institutions and the imperatives of technical systems that do not share their aims. This is not an ontological deadlock. It is a matter of organisational design and the managerial epistemologies that shape it. Habermas is useful here because he helps us see that contradiction need not be romanticised. It can be diagnosed. And, once diagnosed, it can be linked to the institutional conditions that allow it to function under the banner of progress.

If this sounds like a peculiar place to begin an inquiry into digital education, that is because we have grown far too accustomed to treating EdTech as a neutral enhancement rather than a cultural artifact. The platforms that claim to support teaching are not simply tools. They are systems built upon a particular vision of what education is, how it works and who gets to define it. When those systems promise empowerment while streamlining pedagogy out of the picture, we are no longer dealing with a design oversight. We are witnessing a legitimation crisis with a user interface.

3. Education as Relational Uncertainty: What EdTech Misses

It is possible that the only people who still take uncertainty seriously are poets, children and the few remaining philosophers who haven’t joined a product team. Education, for all its institutional trappings and bureaucratic schedules, is fundamentally an encounter with the unknown. It is not simply that we don’t know what a student will say. It is that we don’t even know what kind of subject might emerge in the act of learning. Gert Biesta calls this the ‘beautiful risk’ of education. And if that phrase sounds a bit precious, it is worth remembering that most systems built to improve education are designed to eliminate precisely that risk. In doing so, they also eliminate the beauty, which is rather more than a decorative flourish. It is the condition of education being anything more than the replication of known outcomes.

This element of uncertainty is not merely practical. It is epistemological. Sharon Todd, building on the work of Emmanuel Levinas, reminds us that the pedagogical relation begins with an encounter that cannot be fully anticipated. The other arrives not as a data point but as a disruption. One does not teach to assimilate the other to one’s plans. One teaches while being interrupted by the other’s presence. This is not a flaw in the system. It is the system, if one could still call it that. To design education as though the learner were an input variable in a well-calibrated formula is to mistake the entire premise of the encounter. And yet this is precisely what EdTech platforms tend to do, with the cheerful confidence of someone who has never been contradicted by a ten-year-old.

Teaching, as Deborah Britzman argues, is not a matter of mastering a toolkit and applying it to interchangeable scenarios. It is an affective and negotiated practice shaped by desire, ambivalence and institutional constraint. One does not so much learn to teach as stumble into teaching, surrounded by contradictory demands and a vague sense that none of it is quite working. Britzman is refreshingly unapologetic about this. The chaos is not a sign of failure. It is the texture of the work. The fact that EdTech imagines this chaos can be rendered manageable by a dashboard and a few well-placed nudges is not just optimistic. It is philosophically confused.

Maxine Greene, for her part, insists that imagination and ambiguity are not distractions from real educational work. They are what allow the not-yet-known to emerge at all. Without ambiguity, all we can do is confirm what we already think we know. Without imagination, education loses the capacity to reach beyond its own conditions. These are not sentimental attachments to fuzzy thinking. They are rigorous commitments to a world in which meaning is not delivered but discovered – often sideways, occasionally by accident and always in the company of others who refuse to play along with the script.

Paulo Freire, whose work is so frequently invoked and so rarely understood, gave us one of the clearest accounts of education as mutual transformation. Dialogue, for Freire, was not a method but a mode of being with others. One does not educate by delivering information into another’s mental inbox. One educates by entering into a process of co-formation, in which teacher and learner alike are changed. It is hard to imagine a principle more foreign to the design ethos of most educational technologies, which tend to treat the user as a mildly reluctant recipient of predetermined knowledge, to be coaxed into compliance through gamification or adaptive sequencing.

What these thinkers share is not a nostalgic attachment to the ineffable. It is a recognition that the educational event is irreducibly uncertain and that this uncertainty is not a bug but a feature. There is, in fact, an aporia here – a foundational difficulty in reconciling education’s indeterminacy with any system that demands control. The problem with EdTech is not just that it fails to resolve this aporia. It is that it does not even recognise it exists. It treats the ‘problem’ of education as one of inefficiency rather than one of irreducible relationality. And in doing so, it designs systems that are, at best, educationally irrelevant and, at worst, philosophically incoherent.

4. Systemic Rationality and the Structural Reproduction of Misalignment

It is tempting to imagine that the trouble begins when EdTech arrives, like an overconfident intern, into the grand old institution of education. But the real comedy lies in how well-prepared that intern is. The managerial rationality that structures most EdTech ventures is not borrowed from schools. It is native to the world of startups, corporate boards and product teams – whose governing assumptions about scale, efficiency and control happen to dovetail neatly with the newer regimes of educational reform. This is not a case of values being corrupted by contact. It is a story of pre-existing compatibility. Both systems are already optimised for optimisation.

Jürgen Habermas, whose prose often reads like the minutes of a particularly joyless committee, nonetheless gives us the perfect phrase: colonisation of the lifeworld. In this framework, domains once organised around ethical relation and interpretive meaning become subordinated to systems of instrumental control. Education, once thick with unpredictability and ethical stakes, now marches to the beat of standardised assessments and audit-ready outputs. In such a system, learning must be observable, outcomes must be measurable, and ambiguity is rebranded as inefficiency. Pedagogical value becomes indistinguishable from logistical performance.

EdTech fits seamlessly into this logic – not because it was designed to support schools, but because it was designed to support systems that think like schools now do. The tech sector’s enthusiasm for universal frameworks, frictionless scalability and data-driven decision-making needs no encouragement from education policy. What it does need is a context in which such logics appear not just viable but virtuous. And educational institutions, already under pressure to perform their effectiveness in managerial terms, provide just that. The alignment is not accidental. It is structural, pre-tuned and profitable.

The resulting contradiction is not a misunderstanding between mismatched partners. It is a perfectly functional relationship with a deeply dysfunctional outcome. EdTech amplifies the very tendencies in education that reduce teaching to delivery and learning to compliance. The contradiction appears only when we recall that education once meant something else – something less efficient and far more difficult to explain in a quarterly report. From within the system, however, no one is confused. Everything is working as it should. That is precisely the problem.

This is why critique must do more than lament the loss of pedagogical meaning. It must analyse the infrastructure that makes this loss look like progress. The language of improvement – streamlining, scaling, optimising – has already absorbed and redefined what counts as education. Any meaningful challenge to this system requires more than a better product. It requires a different theory of value, one that resists the translation of pedagogical complexity into product-market fit. Until then, the misalignment between what education claims to be and how it is operationalised will persist – structurally, predictably and profitably.

5. The Failure-Consistent Architecture of EdTech

One of the more charming delusions of the tech sector is its unwavering belief that expertise is fundamentally portable. Success in one domain is presumed to grant insight into all others as if closing a SaaS deal with a fintech company in Berlin uniquely qualifies one to redesign a fourth-grade math curriculum in Cleveland. The market, after all, rewards confidence more than comprehension. This belief in domain-neutral mastery leads to a curious professional migration in which the same cohort of product managers, growth strategists and UX researchers floats from one industry to the next, trailing agile rituals, dashboards and war-room sticky notes. In this setup, education becomes just another vertical – like healthcare, but with more stickers.

The result is a structure that reliably fails to reflect pedagogical realities yet remains structurally insulated from that failure. One might call this a failure-consistent architecture. It is not that the system crashes or collapses under the weight of its misalignment. Rather, it absorbs that misalignment into its very design. Educational expertise is not excluded outright – it is simply made optional, contingent, and, when inconvenient, disposable. It shows up in the form of consulting contracts, advisory boards and user panels, all designed to generate the impression of inclusion while carefully containing any threat to the product roadmap. The message is clear: pedagogical knowledge may inform the process, but it must not interrupt it.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the field of user experience research, which in EdTech often functions less as inquiry and more as corporate divination. Researchers conduct interviews with teachers to identify ‘pain points,’ which are then alchemised into feature requests, design tweaks, or key performance indicators. The teacher is positioned as a user, and the classroom becomes a site of behavioural inefficiency to be optimised. This approach does not ask what knowledge is or how it emerges. It asks what gets in the way of clicking the next button. The complexities of teaching – its temporal rhythms, its affective labour, its relational depth – are flattened into frictions to be sanded down.

This methodological habit is not a bug in the system; it is a feature. It ensures that products remain legible to investors and scalable to markets, even if they become increasingly illegible to those teaching. The system solicits just enough insight to claim fidelity to educational practice, while filtering out anything that might destabilise its assumptions. This is the peculiar genius of EdTech design: it can claim to be teacher-informed while remaining strategically teacher-proof. It thrives on input it cannot afford to integrate.

In such a configuration, failure does not produce crisis. It produces iteration. And iteration, as any product team will tell you, is just success waiting to happen. The architecture holds, because the criteria for holding are not educational. They are logistical, financial and performative. What counts is not whether the product deepens learning but whether it performs well in demos, complies with procurement checklists and scales across districts. Pedagogy, meanwhile, becomes the ghost in the machine – consulted when needed, ignored when necessary and always presumed to be grateful for the attention.

6. Research as Legitimacy: The Closed Circuit of Optimisation

EdTech has developed an ingenious strategy for validating its products without changing them. It is called research. This research often takes the form of teacher interviews, focus groups, or user testing sessions, which produce a data trail just credible enough to satisfy internal slide decks and external funders. What is being measured, however, is rarely pedagogical insight. It is the friction teachers experience when trying to operate within a system already structured by metrics, constraints and managerial logic. These interviews do not open space for pedagogical knowledge to contest the system. They ask it to help the system run more smoothly.

The result is a kind of epistemological laundering. Teacher voices are cited, tabulated and occasionally quoted in italics, but only after being translated into problems the system already knows how to solve. If a teacher says a tool feels dehumanising, this becomes a note about user experience. If they say it undermines inquiry, this is logged as a request for more interactive features. Judgment is flattened into feedback. Inquiry is recoded as usability. The entire practice begins to resemble a kind of methodological ventriloquism in which the teacher speaks only what the system is ready to hear.

In this framework, pedagogical judgment becomes a liability. It cannot be systematised, and it tends to produce questions no product owner wants to see in a Jira ticket. Rather than treat this complexity as foundational, EdTech design treats it as a drag on the system’s capacity to optimise. The goal becomes not to engage the interpretive, ethical and affective dimensions of teaching, but to suppress them in the name of frictionless experience. Optimisation becomes its own justification, untethered from any account of what learning is or why it matters. In this schema, pedagogy is noise: resonant, inconvenient and best filtered out.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the current vogue for personalisation. A term once associated with differentiated learning and student agency now refers almost exclusively to adaptive sequencing algorithms. Personalisation has come to mean not epistemic co-agency but the automatic adjustment of content delivery pace. The learner is positioned as a behavioural node, their preferences inferred from click patterns, their needs presumed legible to back-end logic. There is no space here for uncertainty, for resistance, for the moments of not knowing that make learning matter. There is only optimisation.

All of this, of course, is wrapped in the warm language of responsiveness. But what is being responded to is not the content of what teachers or students say, but the consistency with which their responses can be converted into scalable solutions. Research becomes not a space for new understanding but a device for operational containment. It confers legitimacy not by integrating pedagogical complexity but by demonstrating that it has been consulted and then properly managed. The system appears educational because it has performed the rituals of educational inclusion. What it has not done is ask what education requires.

7. Evidence of Legitimation Crisis: Contradictions in Practice

For all its aspirational language about transformation, EdTech often ends up producing systems that are either unused, underused or creatively subverted by the very educators they were designed to support. Districts spend millions on platforms that never make it into daily instruction. Tools are adopted with fanfare, then quietly retired, left to haunt the bookmarks of teacher laptops like digital ghosts of procurement past. This is not simply a matter of technical glitches or poor onboarding. It is evidence of a deeper contradiction between the institutional promise of innovation and the lived realities of pedagogical labour. The software is implemented, but the practices it presumes do not follow.

Teachers, for their part, are frequently consulted in the design process but rarely in a way that grants them conceptual authority. Their insights are gathered, segmented and often celebrated, yet almost never allowed to alter the basic epistemic framework of the product. They are treated as validators, not theorists. Their professional judgment is welcome so long as it confirms the assumptions already embedded in the design. The result is a peculiar form of inclusion that manages to exclude everything that makes teaching intellectually and ethically demanding. Educators are present in the process but pedagogically absent from the outcome.

This structural exclusion generates not only practical failure but affective estrangement. Teachers recognise the mismatch between the rhetoric of empowerment and the actual constraints of implementation. They hear themselves invoked in slide decks, only to find themselves omitted in strategy. Over time, this disconnect erodes trust – not because teachers are cynical, but because they are observant. They see that the systems claiming to centre them often reroute around them. And while the branding continues to speak in the idiom of equity and agency, the infrastructure speaks in the logic of compliance and scale.

What Habermas helps us name here is not just failure but crisis. A legitimation crisis occurs when a system can no longer sustain the appearance that its actions are aligned with its professed values. EdTech claims to support learning, empower teachers and democratise access. But its operational logic consistently undermines these aims. The contradiction is not an unfortunate byproduct of growth; it is the condition that allows growth to continue while pedagogical coherence unravels. And it is this gap – between promise and practice, between discourse and design – that gives the system away.

The crisis, in other words, is not a sudden rupture. It is a gradual unspooling of credibility, visible in unused licenses, disillusioned educators and the increasingly hollow language of transformation. What fails is not just the platform but the idea that education can be re-engineered without understanding how it works. The contradiction is no longer hidden. It is routinised, normalised and archived in purchasing decisions and user metrics. And yet, like any good crisis, it continues to be managed through performance: updated dashboards, refreshed branding and the occasional keynote speech assuring everyone that this time, the product will be different.

8. Conclusion: From EdTech to AI – The Crisis Deepens

Artificial intelligence did not arrive on the educational scene as a philosopher, a teacher, or even a decent bureaucrat. It entered, rather, as a very efficient assistant with an inflated résumé, ready to make sense of an institution that had already misplaced its sense of purpose. The marketing script is familiar: by automating the routine, AI will allow teachers to focus on what matters – relationships, presence, connection. It is a comforting promise and one that has the added benefit of sounding humane while remaining entirely operationalisable. But what this promise actually performs is not a restoration of relational time but an acceleration of the very system that displaced it. When lesson planning is tied to outcome data, when instructional materials are sequenced by algorithm and when teacher inputs are optimised for efficiency, the space for pedagogical relation does not expand. It becomes ornamental – valuable, perhaps, but only in the sense that it decorates a system already running on different priorities.

What makes this configuration particularly instructive is the way it draws on relation as its premise while designing environments that leave less and less room for it. AI is said to relieve burdens so that teachers may connect more deeply with students. But this rationale merely reframes displacement as benevolence. The very need for AI is justified by the absence it has helped produce. And in that move, the system reclaims legitimacy not by correcting its epistemological narrowing, but by branding that narrowing as its own solution. The contradiction, in other words, becomes the rationale.

This is not an indictment of AI in the abstract. It is a diagnosis of the conditions under which AI is being deployed: conditions defined by platform logics, institutional pressures and a managerial epistemology that treats learning as a delivery problem to be solved. Within such a frame, the introduction of AI does not unsettle the status quo. It consolidates it. It turns pattern recognition into pedagogy and substitutes responsive prompting for the recursive uncertainties of real teaching. Interpretation itself becomes redundant. Meaning is no longer made; it is retrieved.

To address this does not require nostalgic appeals or analog sanctimony. It requires a modest suspicion toward the premise that the future of education can be charted by systems designed to bypass its core commitments. Teaching, however messy and inefficient, is not a function to be delegated. It is a form of attention to what exceeds the system’s grasp. Insofar as AI can support that kind of attention, it might serve education. But under current conditions, its role is largely to simulate support while accelerating the managerial architectures that have already rendered pedagogy an afterthought.