To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticizse power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights. Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny

There was once a little boy who was afraid of the dark. So what? It’s not unusual – lots of children have the same fear. But he was not just an ordinary boy – he was a prince. Just try to imagine it: the little prince sleeping in his huge and cold bedroom in a stone palace with no heating, his bed shrouded by crimson damask curtains that occasionally stir in the wind, perhaps the wind will whistle, he hears voices from outside, somebody shouts, something rustles in the corner of the big room, suddenly some unknown sound, some little creature or piece of paper…. And the prince, under his thick blanket, is scared to death. And so when he grew up, the prince decided to do something radical. Now that he was King, he would ban the dark!

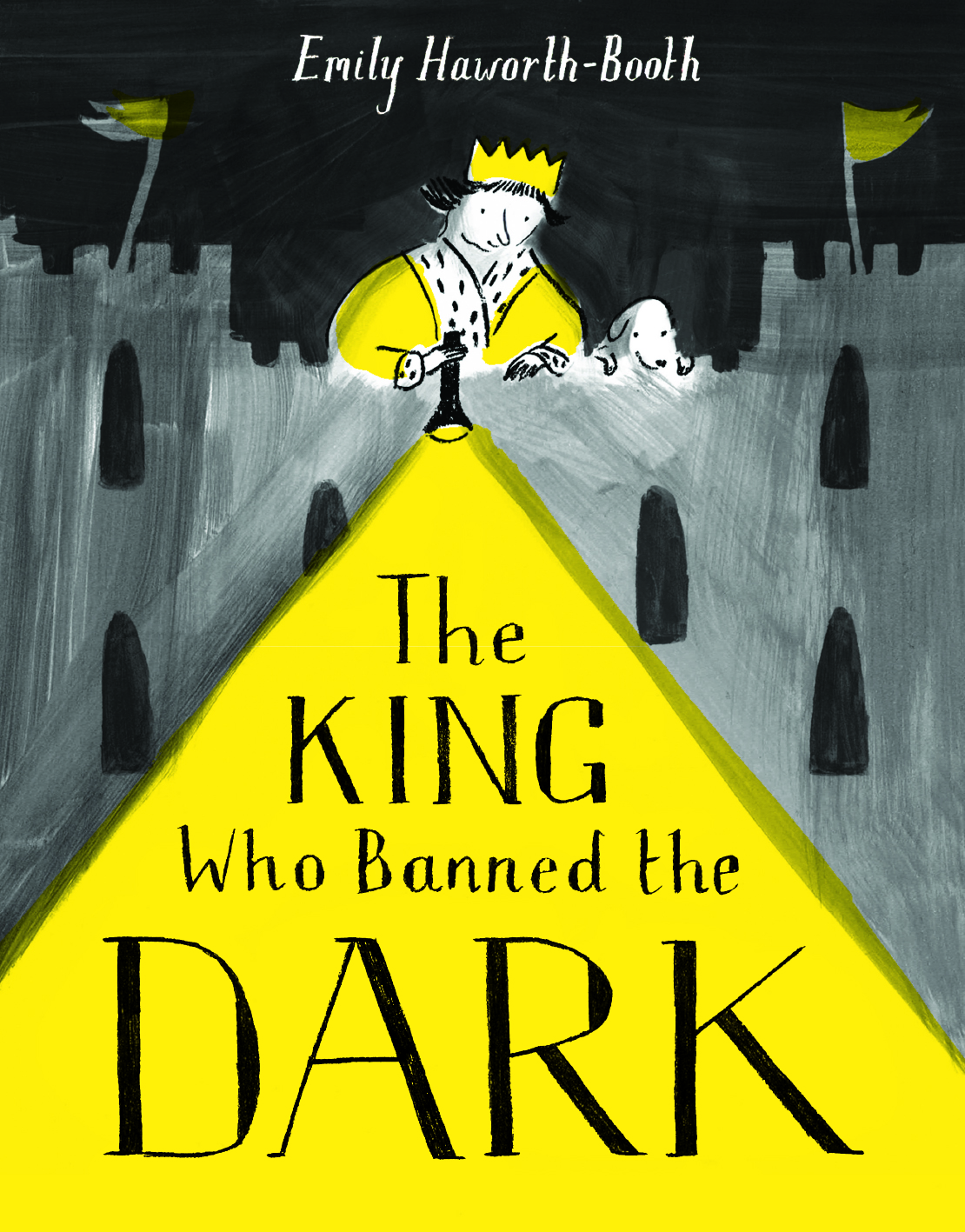

Thus begins The King Who Banned the Dark, a complex, multiple award-winning picture book for adults and children by the English writer and illustrator, Emily Haworth-Booth, published by Pavilion Books in 2018.

The first day of his rule, the King informed his advisors of his plan to ban the dark, but they were worried. They thought the King might turn the people against himself, that they might rebel. The advisors thought it through and came up with a brilliant, tried and tested idea. They advised him to convince his subjects that the ban on the dark was their idea, and his plan might well be a hit. The subjects, who had never ever considered the dark before, let alone experienced it as something bad, suddenly became convinced that the dark was the source of all evil, responsible for all their problems, that it was ‘stealing their money and taking away their toys and sweets.’ And so they marched to the palace and begged the ruler to ban it. ‘Very well!’ said the King and banished the dark from his land. A huge artificial sun was set up over the kingdom, curtains were taken down, anti-dark hats ordered, people were constantly awake and celebrating, until they got terribly tired of such a great deal of light and celebration.

In brief, the people realised that they had made a mistake and that perhaps wanting the dark to be banned was not such a good idea. But what were they to do? The King’s light inspectors were lurking everywhere and punishing anyone who tried to put out the light. The King was informed that the people had started to grumble, suddenly sceptical about the decision to forbid the dark, and the advisors came up with a new plan: they would put on a lavish party for the subjects, it would be ‘the brightest thing of all,’ in order for them to stop thinking and second-guessing the King’s decisions. But the people were fed up with it and not even a party could save things. Instead, there were a few bold citizens who stood out and acted bravely and for the common good. Their actions led to major changes. In the end, the King repealed the ban on the dark and solved his own personal fears by sleeping to a little nightlight.

The King Who Banned the Dark is an allegory and can be understood at several levels. It can be read to children as a story about fear – each one of us is afraid of something, and it is therefore important to have somebody by our side – someone to calm us down and look after us. The prince seemed to have been by himself – perhaps the King and queen were too busy ruling or having rollicking court parties, who can tell? In any case, they did not manage to rid the prince of his terrible fear.

But this is also a story about the importance of truth and knowledge and the harmfulness of manipulation and indoctrination. Fears have to be understood; we have to enlighten ourselves with knowledge. The ancient Greeks, who did not understand the laws of physics well enough, thought that lightning was sent by the gods when they were angry. In the Middle Ages, when there was too little understanding of medicine, it was thought that people who healed others (often women) had some supernatural power and should be burned at the stake for it. This is particularly important today, when the phenomenon of post-truth, coupled with irrationality and receptiveness to conspiracy theories, has led to basic scientific premises being called into question.

The concept of post-truth was first used by American playwright Steve Tesich in 1992. Since then it has come into wide use, as it seems that we are living in a time when emotions and personal opinions are becoming ever more important, and truth is ever less so, even when it is scientifically verifiable. Social media have had a huge impact on this, enabling individuals to spend big swathes of time exclusively in the circle of people who share their opinions, which gives them little cause to check out the accuracy and/or truthfulness of their assumptions. It is incredible that today there are dangerously indoctrinated people who are convinced that the Earth is flat or that vaccination is going to harm their children. It is therefore important that their fears are addressed with knowledge, information, and truth; it is vital not to be led astray by propaganda, irrationality, or unreliable and unfounded sources of information.

The well-known saying be careful what you wish for, lest it come true can be applied to the whole of The King Who Banned the Dark. When the people sought and obtained the King’s ban on darkness, both sides were content, as the author points out: ‘And because everyone had got what they thought they wanted, everyone thought they were happy.’ What a mistake they made. The author seems to be telling us that everybody makes mistakes sometimes. This is a good opportunity to talk to the children, to explain that mistakes are a part of life, and we should avoid digging our heels in once we realize we are wrong. The end of the story, when reason wins out, illustrates this point: the King understands his mistake, rescinds the ban on the dark and starts to sleep by a nightlight: had he done that in the first place, the whole mess could have been avoided.

The notion of responsibility is also important in this story, for many of our decisions involve other people and affect our surroundings. Therefore, it is crucial to behave responsibly and consider the consequences of our decisions: just as the King had a direct impact on the lives of his subjects by his ban on the dark, in everyday life there are countless situations in which we have to think about others – from having to pick up dog dirt from the street so that someone behind us should not tread in it, all the way to curbing excessive consumption and hoarding which creates unnecessary trash and exploits cheap labour.

Although it offers various topics you can discuss with children, The King Who Banned the Dark is very much a story for adults. Its plot is set in feudal times, but it is essentially about the nature of power. It can be read as a story about totalitarianism, a political system that does not tolerate individuals, freedom of thought or any kind of criticism. It deceives its own citizens for the purpose of achieving its objectives – real truth is unimportant, the goal being rather to convince the people via the media and other means of an illusion that is usually aimed at creating or maintaining some division. In this story, light and dark are a universal metaphor of the division into us and them, into those who belong and those who do not, the dangerous ones who need to be eliminated for our well-being. More than once in history has this kind of manipulation and indoctrination led to the exclusion of Others with terrible consequences.

In her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt writes that the essence of totalitarianism is to convince a people that it is real. She says that the strength of totalitarian propaganda inheres in its ability to isolate the masses from the real world, to behave as if the new reality is the truth, and to normalise it. If everyone in a society, or at least the great (mainly unthinking and passive) majority starts to be convinced that the false is true, a fruitful platform for all kinds of manipulation is created. This is also a vitally important message for democratic society today – the story reminds us that truth does exist and that it is extremely dangerous to forget it, to stop wondering what is correct and what is incorrect.

The King Who Banned the Dark underlines the importance of critical thinking. When the King’s advisors started to spread rumours against the dark among the people, the subjects did not view them critically but accepted them as truth, only too ready for an external enemy, in this case, the dark, whom they could blame for their problems. It seemed to them that, in fact, they had always hated the dark – how could it be otherwise? This indoctrination of the people is illustrated by a teacher who writes ‘why the dark is bad’ on the blackboard, feeding the new ideology to the children from the start. This is particularly relevant today, at a time when children spend many hours uncritically consuming Internet content. It is therefore vital to talk to young people about all kinds of information, to make them think about false or true facts and where to check them. They also have to understand that there comes a time when we have to stop following others and start believing in ourselves.

The moment in the story when questions begin to be raised about the seemingly incontestable undesirability of the dark parodies the typical response of authority to subversive thinking. To deflect criticism, the King’s advisors resort to spectacle: here a lavish party, but it could be a military parade, a soccer championship, the Olympic Games. Isn’t it similar in today’s democratic society? In order to forget real, pressing problems like inequality or pollution, we are surrounded by hollow entertainment, phenomena for automatic consumption of rapid and superficial contents that arise not so much from stupidity as from passivity: celebrities that sing, dance, cook, dress or undress…. As if it were some organised dumbing-down movement meant for the passivisation of the citizens who in a democracy should be active and making use of their freedom.

The King Who Banned the Dark is also a story about the importance of diversity and contrast. When the dark was first banned, people liked it, because they could stay awake and celebrate all day long. But they got very tired soon because, naturally, people need the dark to value the light and to be able to recognise it at all. This is illustrated by the effective metaphor of the firework display at the end of the tale. The royal advisers put on the fireworks for the people, but the huge artificial sun created such a bright light that the fireworks could not be seen at all. The message is clear: we need the dark to be able to see the light, and to sleep, and to rest. Life under the constant glaring sun can literally be interpreted as a method of torture – prisoners are sometimes driven to insanity with the constant bright light in their cells that makes it impossible for them to focus, losing their sense of time, and being incapable of thinking and resting. But this constant illumination can also be considered as a metaphor for excessive staring into dazzling screens. For normal functioning, and particularly for creativity and thinking, people need moments of silence, nature, contemplation, reflection and being alone. Yet today it really seems increasingly hard to find them.

The fact that the people in the tale got tired of light and constant celebration is a very good lesson for children. We have to work very hard in order to value the result of our efforts, and that includes doing the dirty work, things we don’t like. Our rest is well-deserved only after we came to know the satisfaction in trying, even failing. On the other hand, constant entertainment results in futility, boredom and ignorance, perhaps even mischief, and nothing explains this better than the Protestant saying the devil finds mischief for idle hands.

Readers can only hope that, as in this story, they will live to see a rational resistance to superficiality, to that constant dazzle, behind which no true, real content is concealed. For when it became clear that all were tired of so much light and celebrating and that they needed a change, the guards had to be outwitted, and the artificial sunlight switched off. At this moment, The King Who Banned the Dark becomes a story of resistance and the possibility of the individual to oppose the unthinking, automatic and often dangerous straying of the mass. Some people will be able to separate themselves from the crowd, shout that the emperor has no clothes, and really set off and work for their own and for the common good. Real changes will be instigated by thinking individuals who want to do good, especially if they have some help and don’t feel completely alone in their efforts. That is what happened in this story – organised resistance bore fruit.

The whole picture book The King Who Banned the Dark is illustrated in black, white and yellow tones, and besides a pencil, the artist has used ink, watercolour, charcoal and crayon. The cover is black-grey-white-and-yellow, very simple, but if you turn it to the light (!), in the centre, you will notice that the yellow beam of light has been applied uncommonly heavily, in an engaging impasto manner. After reading the whole tale, it seemed to me that this beam of light symbolises enlightenment, in the philosophical sense of belief in human reason, in the possibility of arriving at the truth by oneself and building upon it intellectually, a process of becoming a thinking human being.

Emily Haworth-Booth has, in fact, played very effectively with colours, for the first part of the book is dominated by black, white and yellow; at the end, when civil disobedience has overturned the ban and allowed the dark, the author has brought in a palette of new and varied colours: the story has livened up and life has stopped being grey and monotonous. What can we conclude from this? The dappled, mottled, colourful variety of life has to be won: individuality, creativity, thought and freedom are achieved only with effort and by taking responsibility. The majority will attempt to shove us into their own blank moulds and manipulate us so as to be more like each other, so that nobody stands out, for everyone to wear the same hats and propagate the same values. They will try to persuade us that we have to turn against them, whomever they might be. But stories give us meaning and organise our thoughts on reality. So read The King Who Banned the Dark to yourself and your children, feel free to think about it and use it as a shield against manipulation and indoctrination.

NOTE: This text was first published in Croatian, http://ideje.hr/dodirne-tocke-slikovnice-kralj-koji-je-zabranio-mrak-s-izvorima-totalitarizma-hannah-arendt/