The concept of Empire is dedicated to the idea of peace. (Hardt & Negri, 2004)

A structuralist analysis of the US permanent war economy follows the governmentality of the market as revealed by mainstream economics to make three underlying assumptions: (i) peace is a normal state of affairs that characterises societies that are both developed and democratic; (ii) ‘economic development, made possible by industrialisation, is the fundamental instrument for sustainable peace’; (iii) economic development essentially means ‘Westernisation,’ the adoption of Western values especially freedom and democracy, that is a natural consequence of development. In this latest phase ‘neoliberal peace’ is commodified and subtracted out where Peace Corps intervene around the globe.

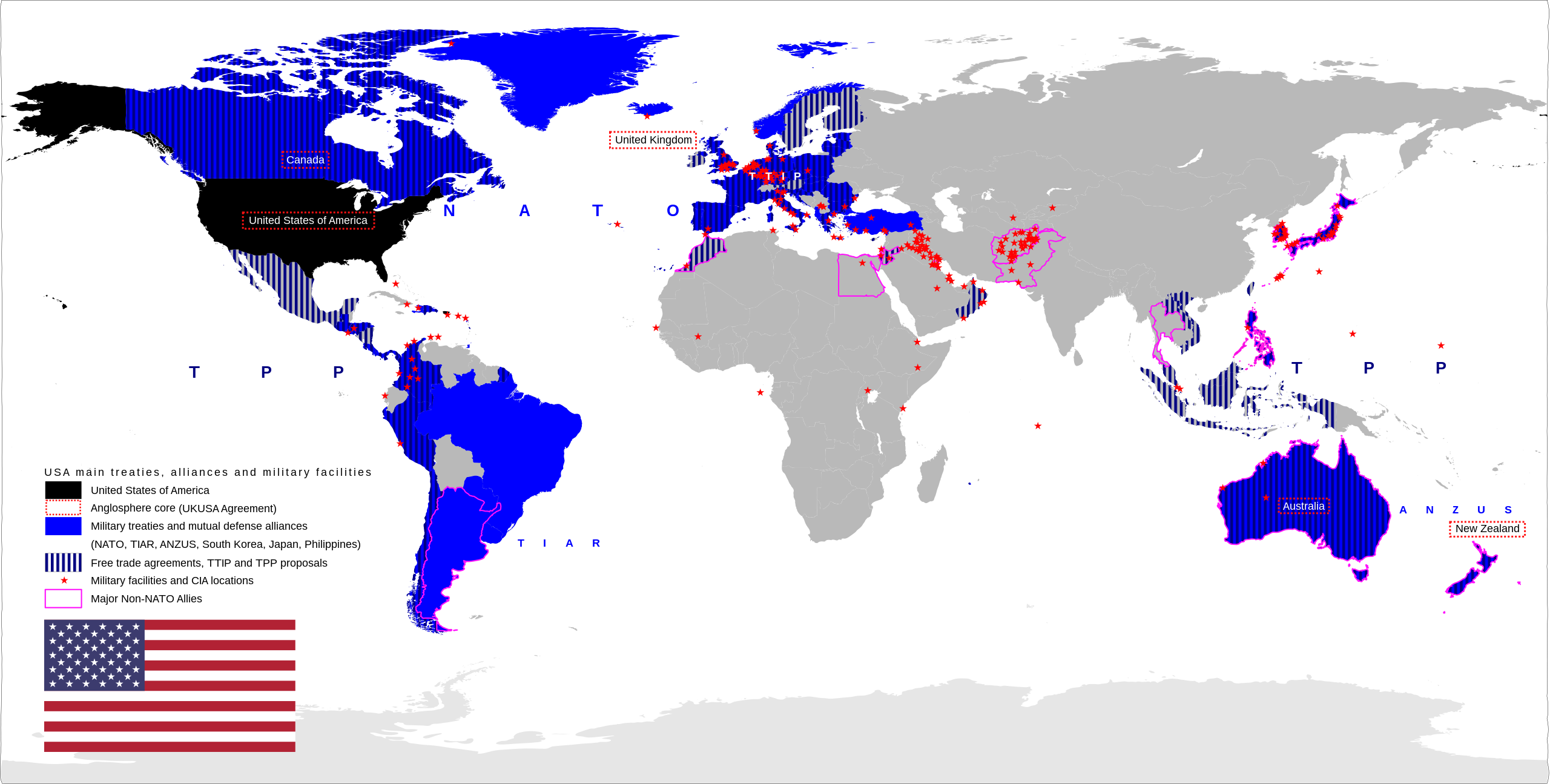

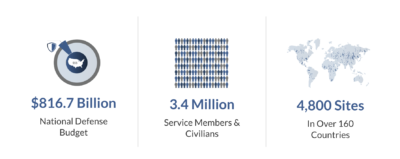

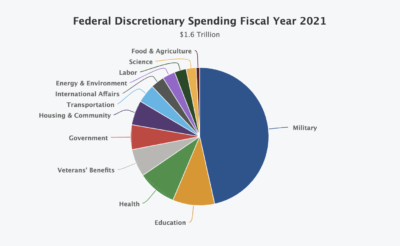

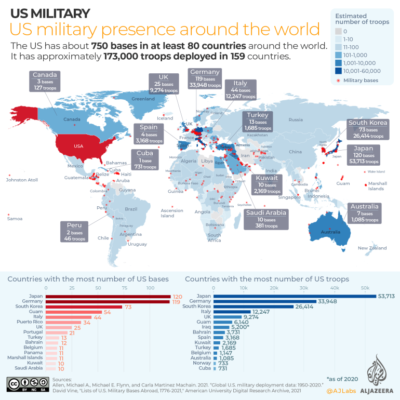

Some structuralist insights into the nature of the US-dominated world order can be quickly demonstrated through the scope and extent of the current US defence apparatus (Figure 1), Federal Discretionary Spending (Figure 2) and the US Military Presence Around the World (Figure 3).

Figure 1. The US Defence Budget 2023

Figure 2. Federal Discretionary Spending 2021

Figure 3. The US Military Presence Around the World

The hidden structuralist negative assumption is that violence at home and abroad is also a natural consequence of the US model, both emanating not just from ‘gun culture’ (an amalgam of constitutional rights, market freedom and lobby politics) but also from the US as a permanent war economy, a structuralist concept. In the US, where there are 120 guns for every American, the highest in the world, where Americans own 393 million (46%) of the 857 million civilian guns available in the world, where 44% of American adults live in a household with a gun, gun culture trumps all other rights threatening the right to life. As Grinshteyn and Hemenway report: ‘US homicide rates were 7.0 times higher than in other high-income countries, driven by a gun homicide rate that was 25.2 times higher. For 15- to 24-year-olds, the gun homicide rate in the United States was 49.0 times higher.’ School shootings are a form of gun violence, and the US tops the list of countries with the most school shootings, with 288 incidents in the period from January 2009 to May 2018. As CNN reports, as of September 28 this year, there have been 54 school shootings (17 on college campuses, 37 on K-12 school grounds), leaving 27 dead and 58 injured.

Gun culture is supported by the whole gamut of American history – its colonisation, slavery and plantation agriculture, frontier origins celebrated in popular culture as ‘cowboys and Indians’ and gunfights as a method for settling disputes, the Civil War, and American participation in WWII and, as one source claims, a staggering 37 US military interventions since WWII killing more than 20 million people. CGTN reports: ‘From 1945 to 2001, among the 248 armed conflicts that occurred in 153 regions of the world, 201 were initiated by the United States, accounting for 81 per cent of the total number.’ According to Boine and colleagues, US gun culture is comprised of subcultures – recreational, self-defence, symbolic Second Amendment protection – and supported by academies, school cadet training, and the major role of the military in US society. Ubiquitous gun violence in the US is also sustained by a cultural apparatus that sustains a continual Hollywood stream of violent acts and images. The popularity of gun violence in pop culture is part of the process of its normalisation. Douglas Kellner views it as a form of domestic terrorism and male socialisation, as do critical feminist media views.

War has also profoundly shaped the American economy in the twentieth century. As Rockoff claims, ‘the United States was at war for roughly a quarter of the twentieth century, and, if we include the long cold war, the figure rises to 55 per cent.’ This figure does not include the many smaller conflicts or interventions or military exercises on foreign soil, nor does it define the long war against communism, including the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, and the Ukraine War that many see as a proxy war against Russia. With the so-called ‘pivot to Asia,’ the economic war against China over trade, technology and the international financial system is interpreted by some critics as a precursor to a hot war over the pretext of Taiwan.

Dwight D. Eisenhower warned American citizens of the US ‘military-industrial complex’ in his 1961 farewell speech. The relationship between the military and the defence industry – now the ‘military-industrial-academic complex’ – has become a core part of American policy-making with a military budget of the US military budget of $816.7 billion (2023), which is 12% of all Federal spending, the largest discretionary fund. The US spends more on defence than the next nine countries combined, approximately 20-25% of the US economy. The US Government increasingly outsources important national security responsibilities to over 3000 defence contractors, the top ten in FF22 making up 74% of ships, aircraft and war vehicles. Under the neoliberal war model, contractors now supply much of the specialised services required by American defence and intelligence agencies.

There are 750 US military bases remaining around the planet after the closure of 1000 bases in Afghanistan (Figure 3), and these overseas installations are now scattered across 81 countries, colonies, or territories on every continent except Antarctica. Chris Hedges writes:

The permanent war economy, implanted since the end of World War II, has destroyed the private economy, bankrupted the nation, and squandered trillions of dollars of taxpayer money. The monopolisation of capital by the military has driven the US debt to $30 trillion, $ 6 trillion more than the US GDP of $24 trillion. Servicing this debt costs $300 billion a year. We spent more on the military, $813 billion for fiscal year 2023, than the next nine countries, including China and Russia, combined.

He indicates that the US is ‘trapped in the death spiral of unchecked militarism.’

The permanent war economy, implanted since the end of World War II, has destroyed the private economy, bankrupted the nation, and squandered trillions of dollars of taxpayer money. The monopolisation of capital by the military has driven the US debt to $30 trillion, $6 trillion more than the US GDP of $24 trillion. Servicing this debt costs $300 billion a year. We spent more on the military, $813 billion for fiscal year 2023, than the next nine countries, including China and Russia, combined.

Some Western commentators argue that the US is fighting a proxy war with Russia in Ukraine, which has been in progress now for over a year, with pundits suggesting it will be another US ‘forever war.’ Yet the much-touted Ukraine counteroffensive has made few territorial gains, and there are signs that US aid, already more than US$120 billion, will not be as forthcoming as it has been in the past. Slovakia, a member of the EU, elected a pro-Russian leader who is on record as saying no further aid will be provided to Ukraine.

Forms of realism have made a comeback after the dominance of liberal internationalism and constructivist views in International Relations theory. John Mearsheimer is a prominent (defensive) ‘structural realist’ at the centre of the debate about why Russia invaded Ukraine. Russia is pictured as making a rational decision to preserve its territorial borders against the US-engineered expansion of NATO eastwards, against the planned interference by Victoria Nuland and other US diplomats in the coup against an elected Ukrainian president that goes back to 2013, with the discrediting of Russia’s status as a great power as an American Cold War strategy. Mearsheimer questions the prevailing wisdom of the West that Russian aggression is to blame. As he puts it, ‘Putin … annexed Crimea out of a long-standing desire to resuscitate the Soviet empire, and he may eventually go after the rest of Ukraine, as well as other countries in eastern Europe.’ Mearsheimer suggests that the West bears most responsibility for the crisis: ‘The taproot of the trouble is NATO enlargement, the central element of a larger strategy to move Ukraine out of Russia’s orbit and integrate it into the West.’ He continues:

Elites in the United States and Europe have been blindsided by events only because they subscribe to a flawed view of international politics. They tend to believe that the logic of realism holds little relevance in the twenty-first century and that Europe can be kept whole and free on the basis of such liberal principles as the rule of law, economic interdependence, and democracy.

The tradition of realist thought in International Relations maintains that states will take steps to ensure their own survival in a world that lacks supranational agencies to adjudicate disputes. On this view, the international realm, a sphere of anarchy, is thus always and necessarily a field of conflict and competition. Great powers are ‘concerned mainly with figuring out how to survive in a world where there is no agency to protect them from each other’ and that ‘the [anarchic] international system creates powerful incentives for states to look for opportunities to gain power at the expense of rivals.’ Yet critics like Smith and Dawson argue that structural realism, unlike other forms of realism, cannot provide the non-relist grounds of ontological security or civilisation thinking to explain Russia’s invasion.

The structural realist model no longer supports an interpretation of the US as the sole hegemonic superpower able to intervene in its own interests anywhere in the world at will to maintain the US imperial world order, and Ukraine, following the shambolic US ending of the Afghan War under Biden, is seen to be another example of the limits and waning of American power.

The realist structural view provides a world-historical account that specifies distinct periods of great power rivalry in the pre-WWII era: the emergence of US-Russia bipolarity, the ascendency of the US as the sole superpower after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, the decline of US power, the rise of China and the development of a multipolar world after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. Realist accounts of international relations stand in stark contrast to the neoliberal school of thought, sometimes called Liberal institutionalism, that holds international cooperation is possible and can reduce violence, conflict and competition between states, and structuralism, most often of Marxist or Neomarxist interpretation, that rejects the realist and liberal view of state conflict or cooperation to focus on the underlying political economy and materialist understanding. Constructivism and rational choice explanations where the former, derived from European phenomenology and postmodernism, argues that international politics is a discursive creation shaped by collective beliefs and values and the primary role of ideas, whereas rational choice, associated with neoliberalism, and developed by Buchanan and Tulloch’s (1962) influential The Calculus of Consent: The Logical Foundations of Democracy that argues for a formal rational model in relation to strategic behaviour.

Reassessing Realism: From Empire to network power in a multipolar world

Structural forms of explanation are an important mode of knowledge that examines underlying structures and patterns of social phenomena, often claiming to expose or unearth hidden underlying causes or deep structures that are regarded as universal. The structuralist revolution beginning in Russian formalism at the turn of the century and signalling the fundamental significance of the ‘linguistic turn’ in semiotics represented by Jacobson and Saussure (and differently by Wittgenstein and Peirce) was applied by a generation of French thinkers such as Levi-Strauss, Barthes, Lacan, Althusser and the early Foucault, who sought to demonstrate deep structures beyond the conscious individual subject that governed thinking and behaviour. Structuralism issues a set of challenges to liberal humanism, dating from Kant, that gave humanism a universal essence. Western Marxism, since its Western deviation and theoretical development in the 1920s, developed in diverse ways that have reflected the broader philosophical environment, first, as a theory of consciousness and alienation in the early Marx and then in terms of a materialist base/superstructure model. In this same genealogical strand, the inception of Nietzschean Marxism, which swapped Nietzsche (and Spinoza) for Hegel, by thinkers as diverse as Deleuze and Guattari, Derrida, Lyotard and Foucault. Poststructuralism is regarded as a specifically philosophical response to the alleged scientific status of structuralism to decentre the ‘structures,’ systematicity and scientific status of structuralism, to critique its underlying metaphysics and to extend it in several different directions, while at the same time preserving central elements of structuralism’s critique of the liberal humanist subject or state entity modelled on the same assumptions.

Both Realist and Liberal accounts of International Relations theory externalise the relations between violence and politics outside the state, arguing that violence is the sole prerogative of the state(s) that protects a special set of relations between force and law that can be projected onto the realm of world politics. By contrast, poststructuralist approaches tend to take an endogamous view, arguing that modern political reason exemplified in liberal institutions is itself constitutive of the violence it seeks to eliminate; it is part of the modern political freedom experienced by individuals and part of modern subjectivity often experienced as disciplinary power based on the model of the prison. The autonomous political subject as a reasoning sovereign subject is complicit with the violence of that which constitutes and governs them, including the conditions for life per se.

The poststructuralist critique highlights the increasing significance of issues of self and identity in relation to Enlightenment notions of a universal, stable, unchanging and essentialist self that has served as the core of European conceptions of the citizen-subject. With a post-Nietzschean conception, alternatively, we can talk of a deepening of democracy and a political critique of Enlightenment values based upon criticism of the ways that modern liberal democracies construct political identity. The major problem is that both liberal and Marxist theories construct identity in terms of a series of binary oppositions (e.g., we/them, citizen/alien, responsible/irresponsible, legitimate/illegitimate), which has the effect of excluding or ‘Othering’ some groups of people. Western countries grant rights to citizens – rights that are dependent upon citizenship – and regard non-citizens, that is, immigrants, those seeking asylum and refugees, as ‘aliens.’ The political critique of the Enlightenment demands that we examine how these boundaries are socially constructed and how they are maintained and policed. Global citizenship education grapples with these issues but often without recognising the history sensitive to how these distinctions are a result of the history of colonialism and continue to exercise force in constituting the Global South.

Asli Çalkıvik indicates that the poststructuralist diagnosis implies that ‘modern political reason not only cannot provide adequate tools to understand and address political violence but that as a rationality of rule, it is not immune to it.’ This is the ‘paradoxical character of modernity’ that is the major premise for engagements with security and war. As he summarises: ‘the problem of achieving peace and security not merely as a political project to overcome insecurity, but as a political method to govern life.’ Security, rather than an objection condition to be remedied, ‘is revealed as a form of political subjection, as a political technology of rule,’ a form of rationality echoed in ‘the modern faith in development and progress becomes part of the problem itself.’

This mode of thinking might be seen to emerge from an approach to war from the perspective of Foucault’s concept of governmentality, war as both total and continuous, as he suggests in Society Must be Defended,

politics is the continuation of war by other means. Politics, in other words, sanctions and reproduces the disequilibrium of forces manifested in war. Inverting the proposition also means something else, namely that within this ‘civil peace,’ these political struggles, these clashes over or with power, these modifications of relations of force – the shifting balance, the reversals – in a political system, all these things must be interpreted as a continuation of war.

Hardt and Negri’s Multitude is a Foucault-inspired text on war, published on the eve of the ‘war on terrorism,’ an American-led global counterterrorism campaign launched in response to the September 11, 2001, attacks. The ‘war on terrorism’ had a huge effect on international relations, discursively comparable to that of the ‘Cold War,’ inspired by Leo Strauss and the US neoconservative’s Project for the New American Century, and involving major wars in both Afghanistan (2001-2021) and Iraq (2003-2011), after the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Centre, the deadliest terrorist event on American soil. For Hardt and Negri, this series of events manifested as a shift from ‘imperial peace’ to continuous and total war. As Ayça Çubukçu explains, ‘Empire argues that the transnational globalisation of economic and social relations is coupled, simultaneously, with the parallel emergence of a supranational political sovereignty…legitimated through the universal discourse of human rights, arguments predicated on ‘just war’ theories, calls for and practices of humanitarian intervention, and political valorisations of the ‘effectiveness of global police actions in resolving conflicts.’ This world sovereignty gives way to a ‘postimperialist era’ where no single nation-state is capable of functioning as the centre of the new world power. By contrast,

imperial sovereignty operates through a network form of power – a cooperative yet hierarchical web of global administration and command which links all nation-states, international institutions such as the United Nations, IMF, World Bank, G-8 and WTO, transnational corporations, and benevolent NGOs under a new global paradigm of rule. In this situation, ‘not even the United States can ‘go it alone’ and maintain global order without collaborating with other major powers in the network of Empire’ (Multitude xii). But one problem with this formulation is the possibility that the United States is interested not only in ‘maintaining’ the current imperial order and its supranational tendencies, as outlined by Hardt and Negri, but also in ‘creating’ another, as it may decide.

In Empire and Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire, Hardt and Negri (2000; 2004) offer a radical reading of the contemporary world political economy and an agenda for revolutionary change. Their radicalism is presented as new. They perceive the contemporary world as operating in a novel way. Political power is no longer concentrated in states; state sovereignty has given way to imperial sovereignty. Hardt and Negri are theorists of globalisation who take the contemporary world to function in a way that is distinct from its modern past. The power that states have harnessed and wielded and which has been criticised by preceding modern critics is no longer to be inspected and denounced from a standpoint that is situated outside the boundaries of the power exercised by states and empires. New imperial power is exercised globally and has no inside or outside. They observe,

There is a long tradition of modern critique dedicated to denouncing the dualisms of modernity. The standpoint of that critical tradition, however, is situated in the paradigmatic place of modernity itself, both ‘inside’ and ‘outside,’ at the threshold of the point of crisis. What has changed in the passage to the imperial world, however, is that the border no longer exists, and, thus, the modern critical strategy tends no longer to be effective.

Twenty years on, Hardt and Negri return to their book Empire to assess the changes after the US imposition of a ‘new world order’ developed during the Bush administration. By contrast with twenty years ago, commentators ‘lament the decline of the liberal international order and the death of the Pax Americana,’ and they go on to theorise two spheres – ‘the planetary networks of social production and reproduction, and the constitution of global governance – that are increasingly out of sync.’ The US could easily topple regimes but could not establish the stable hegemony required in Syria and Afghanistan. With Trump’s election, the ideal and reality of a liberal international order faded quickly as he reneged on EU and NATO, withdrew from the Paris Accord, and focused on ‘America First’ and a kind of isolationism. As they argue:

The fact that no nation-state is able to fill the hegemonic role in the emerging global order is not a diagnosis of chaos and disorder, but rather reveals the emergence of a new global power structure – and, indeed, a new form of sovereignty.

First, despite the size of the US military’s budget, the number of bases around the world, its war technological sophistication, and its ‘increasing capacity for destruction,’ the US war machine falters in the face of determined nationalist struggles for the homeland. Second, the US control of the global dollar reserve system has been increasingly questioned and systematically weakened as the BRICS led by China have set up long-term an alternative global financial architecture based on the Asian Development Bank and the New Development Bank that are linked to a new kind of rule beyond Empire based on new internationalisms and the growth of new regional powers in a multipolar world.

Extending Hardt and Negri’s analysis into the Biden era, a new kind of rule is evident in the hurried conclusion to the Afghan ‘forever war,’ the US-NATO alliance that briefly saw a high point of European unity in the first half of 2023 based on Russia as enemy and a billion funding program of the Ukraine proxy war, and then, again, hurried US efforts at building new coalitions and partnerships in the ‘pivot to Asia’ with new military bases and pacts such as AUKUS (the transfer of nuclear technology to Australia), all aimed at containing China and slowing its growth. This US new internationalism after Trump’s populist withdrawal represents a network view of power and rule that depends upon the realisation that the United States can no longer operate alone with impunity but depends upon negotiated coalitions often softened with trade deals and other aid sweeteners, while at the same time the pursuit of economic sanctions against an increasing diverse group of countries, organisations, and people. In one sense, this is to polarise the world into a US-led neoliberal band of economies (US, UK, Canada, Australia and NZ) based on trade, surveillance and technology networks intent on extending US network power especially in the ‘Indo-Pacific’ versus a group of countries led by China and manifest in new networks such as the expanded BRICS, Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), and pursued through the trade bilateralism of the Belt and Road Initiative and the China-Africa Cooperation Vision 2035. The Biden administration’s China strategy, some argue, is ‘great power’ competition with strong echoes of Trump’s position. In the National Security Strategy (October 12, 2022), Biden argued ‘our world is at an inflection point’ between democracies and autocracies and reverts to ‘defending democracy around the world’ based on a ‘belief that the rules-based order must remain the foundation for global peace and prosperity.’ ‘The contest for the future of our world,’ he remarks, is directed at China that harbours the intention and, increasingly, the capacity to reshape the international order in favour of one that tilts the global playing field to its benefit.’

As Yang Jiemian argues, ‘America’s increasingly entrenched view of China as its ‘main security threat’ relies on several problematic cultural, ideological, and theoretical ideas.’ He goes on to outline the case for a ‘profoundly self-centred view of history that fails to account for the historical and cultural complexity of other global actors ‘based on the doctrine of American exceptionalism, in its determination ‘to maintain its global hegemony and sees suppressing China as key to preserving its current international position,’ that paradoxically will hasten the US decline.

This decentring of US power of Empire into a network conception of new partnerships and coalitions, with some limited cooperation through the UN system organisation on global public goods, seems destined to last for the rest of Biden’s presidency and for another four years if he is re-elected after in 2024. It also depends on a multitude of other factors: the outcome of the Ukraine war; the continued unity of NATO; the political stability of the EU in an environment that has shifted to the far-right; the continued shift in the centre of economic power to Asia and newly emergent economies of India, Indonesia, Bangladesh and Vietnam; the growing power and influence of the expanded BRICS countries; the US ‘pivot to Asia’ and the increasing militarisation of the Asia-Pacific. In these circumstances, the prospects for peace do not necessarily look better with possibilities for war and regional conflicts on the fringes of network power and perhaps pinpointed to areas of local engagement around the scramble for resources in a world increasingly facing multiple crises of climate change, global warming, and the collapse of regional ecological systems. If anything like this is the case, then peace education faces massive and monumental tasks, the first of which is to get a clear view of a new set of concepts for understanding the significance of network power.

Only days after writing this essay, Hamas attacked Israel, and, at the time of writing this postscript (October 14), Israel is in the process of retaliating against Hamas with a ground force about to go into the Gaza Strip. Over a million Palestinians and others have been told to leave northern Gaza as soon as possible by the Israeli authorities. Already, several thousand people have been killed, and many more are causalities. The US and UK have both condemned the attack and have gone to the aid of Israel, while much of the Muslim world has rallied in support of the Palestinians, who have been under Israeli occupation for 56 years, ever since the UN resolution to split Palestine into two states. After Israel declared independence on May 15, 1948, a war ensued in which Palestinians were forced off their lands. Following the war, the territory was divided into three, including the Gaza Strip, West Bank and Israel. Palestinians argue they have the right to defend themselves. Biden has called Hamas ‘evil terrorists’ and warned Israel to operate within the ‘rules of war’ – a reference to liberal ‘just war’ theory. The likelihood of a ceasefire or peace negotiations any time soon seems remote with the risk effects on wider world security. Hezbollah and other Muslim groups have indicated they will become involved in the war at the time of their choosing. Escalation is a real risk. Some argue that the war is a failure of the inability to action the two-state solution. There seems little hope of dialogue at this point in the cessation of war and the reconstruction of a permanent peace in the Middle East. Netanyahu has announced an offence against Hamas with a force ‘like never before,’ signalling to the world the possibility of a slow genocide or a grander regional conflict involving other regional powers and also the US and the UK.