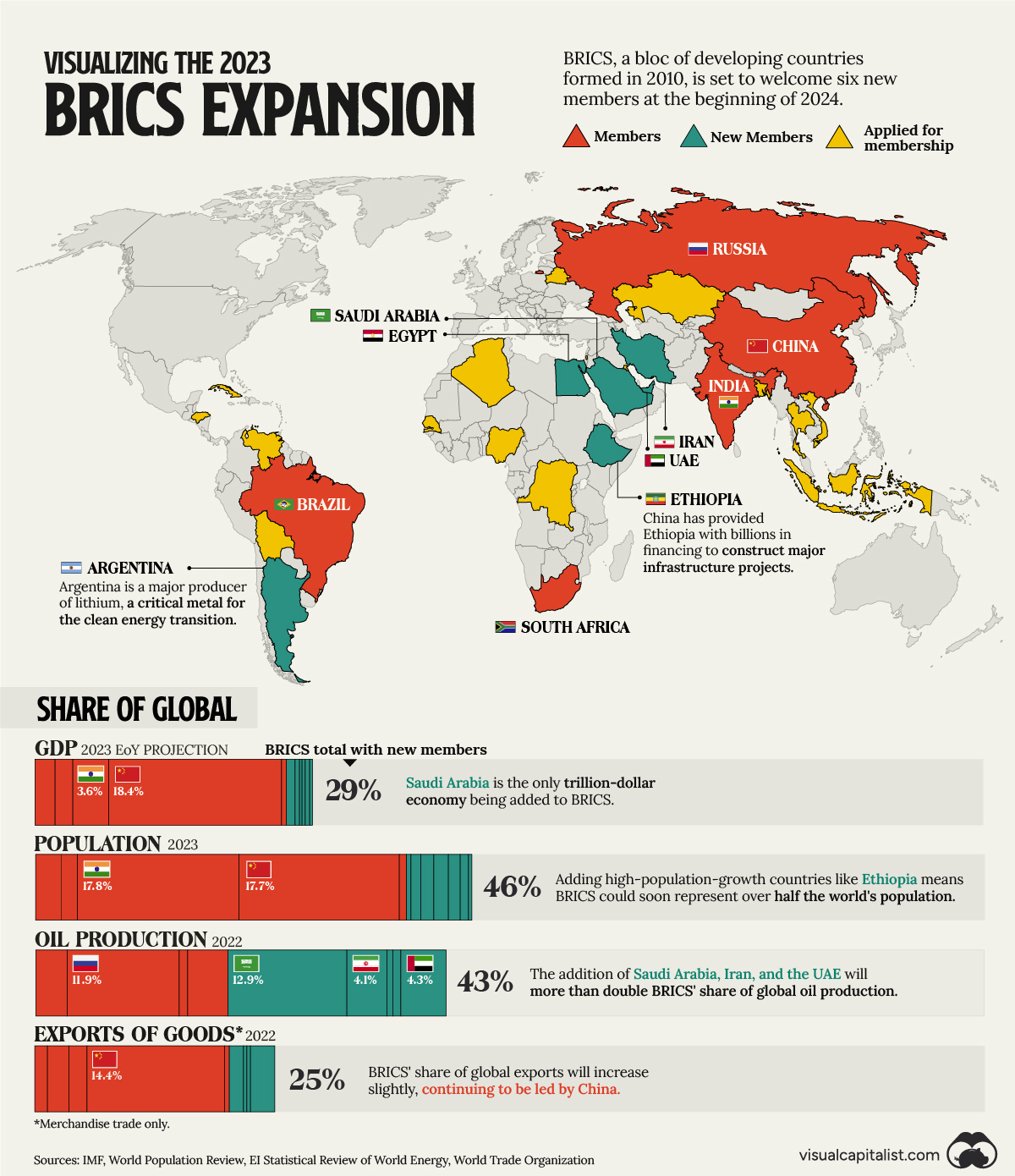

At the two-day BRICS Summit 2023 in Johannesburg (August 22–24), the fifteenth annual summit since the establishment of the organisation in 2006, the five member states of Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa took the historic decision to expand the BRICS membership by adding six new member states Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Iran and Ethiopia. This momentous historical event more than doubles existing membership with an emphasis on four of the 16 Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries, a region that has suffered extended periods of civil war and ongoing low-intensity conflicts following the Arab Spring 2011, the rise of the Islamic State (ISIS) and foreign interventions.

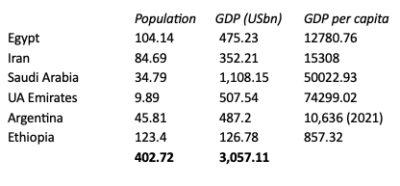

Speaking at the Summit, President Xi said that the BRICS expansion is historic and a new starting point for extended BRICS trade and cooperation. He also suggested that the expansion would strengthen world peace. The expansion includes four MENA (Middle East and North African) countries – Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – as well as Argentina and Ethiopia. Another way of looking at the expansion is in terms of the geographical spatial distribution of the three ME countries, two from North Africa and one from South America, that enhances existing trade links, assures a basis in the world’s oil-based energy system and provides a civilisational diversity. Figure 1 provides a shorthand summary of population and GDP, indicating the relative contributions of new member states.

Figure 1: Expansion of the BRICS11: New Member States (2022 stats)

Geopolitics of Expansion

The ascension of both the two largest countries, Saudi Arabia and Iran, that have experienced strained relations since the 1980s, especially after the Iranian Revolution, over aspirations of regional leadership, oil export policy and US intervention may seem remarkable coming on the heels of a Chinese-brokered deal for the restoration of diplomatic relations on 23 March 2023 with a general rapprochement and exchange visits aimed in part to reduce Iranian support for Houthi rebels with the aim of driving them to a negotiated settlement with the Yemeni government. The Joint Trilateral Statement by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the Islamic Republic of Iran and the People’s Republic of China, an agreement to resume diplomatic relations between them and re-open embassies, discussed means of enhancing bilateral security and trade relations and expressed a desire to enhance regional and international peace and security. Tensions will no doubt remain and require a historical working through, although there are also clearly massive gains for Iran in terms of future regional investment, trade and development, as well as wider BRICS economic involvement.

Saudi Arabia, a traditional US ally, is the second largest in the region, occupying the Arabian Peninsula and the second largest oil producer in the world. It has the largest economy in the Middle East (ME) (17th in the world by PPP) and is the only ME country in the G20. The relationship with the US has suffered on two counts: first, against US sanctions, Saudi Arabia strengthened relations with Russia in 2022 and reduced OPEC oil output and, second, in the same year, signed a strategic Sino-Arab partnership with China, undermining US’s containment of China. Saudi Arabia has disrupted the petrodollar system in place since the 1970s when the US imported oil. In terms of this system, Saudi Arabia would sell its oil for US dollars that were then reinvested in US Treasury bonds. It is more than likely now that oil transactions between Saudi Arabia and China will be settled in Chinese currency. Most Western media have played down the acceptance of the yuan by Saudi Arabia and other countries, dismissing the possibility that the yuan might replace the US dollar and denying the de-dollarisation of the world economy, but it would be unwise to underestimate this trend that is accelerating with many countries such as Saudi Arabia, Bangladesh, India, Argentina, Brazil, Pakistan, Iraq and Bolivia trading in yuan as China internationalises its currency.

The petrodollar system put in place in the 1970s as a relationship between Saudi Arabia, then the largest oil producer and the US, a net importer of oil – a system where the former was persuaded to sell oil in dollars only – is now breaking down. The US became the largest oil producer under the practice of ‘fracking’ although given its environmental consequences, it is not clear how long this will last. The dollar as the global currency for global investment, especially in US Treasury bonds, backed by the system of petrodollars, is also faltering. It could be argued that the ‘Dirty History of Petrodollars’ was in part the reason for the invasion of Iraq and formed the geopolitical background against which the USA first supported former dictator Hosni Mubarak and then overthrew him; the US also helped topple Muammar Gaddafi in Libya and tried to destroy Iran’s economy on the pretext of a nuclear programme. In ‘The Slow Death of the Petrodollar’ (2023), it is claimed that ‘This symbiotic relationship [between the US and Saudi Arabia] is now on its last legs – the Dollar’s dominance of the global oil trade is dying, and ,in turn, the status of the Dollar as the international reserve currency is increasingly in doubt.’ A number of critics suggest that US dollar hegemony based on the practice of ‘petrodollar recycling‘ is no longer sustainable, and the underlying issues of the Iraq war apply to geostrategic interventions by the US in the whole region.

The inclusion of Iran in BRICS requires special mention, given the loss of formal diplomatic relations with the US since 1980 and the strict ban on talks with the US by the Supreme Leader in 2018. The US responded with a trade embargo operating since 1995 and a plan to limit Iran’s nuclear program. Iran is central to US foreign policy in the Gulf and provides a lens to examine US wars and interventions since the Gulf War in 1990–1991, including support for Israel and containment of Russia’s influence. The weaponisation of the international finance system, highlighted by the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA) under Clinton in 1996 and cutting Iran off from the SWIFT telecom banking system in 2018 under Trump, has done untold damage to the Iranian economy and people. Iran’s inclusion in BRICS represents a repudiation of the US sanctions on Iran and US foreign policy designed to isolate Iran. There has been a surge in oil exports, and Chinese imports are booming at the highest level in a decade.

Egypt, officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, with a population of over 109 million, is a large country that spans Africa and the Middle East. It became independent from the UK in 1922 and a republic in 1952 with President Nasser, followed by Sadat. It is ranked 20th by PPP 1.8 trillion (18th) and 41st in terms of GDP at $378 billion, making it the second largest economy in Africa, with trade with other BRICS countries at approximately $25 billion. President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi ratified Egypt’s membership in BRICS’s New Development Bank (NDB) in 2023, contributing $1.196 billion, the highest share for a non-founder of the Bank, representing 2.1 per cent of the voting power. Egypt became the Bank’s fourth new member as part of the first expansion of the NDB’s global reach, with the memberships also of Bangladesh and Uruguay. Argentina, Ethiopia, Iran and Saudi Arabia, as new members of BRICS, will get membership in the New Development Bank, and prospective new members include Algeria, Honduras and Zimbabwe.

Mohamed Hafez (2023) indicates that Egypt and China have diplomatic ties stretching back to 1956, when Egypt recognised the Republic of China. China has been a strong investor in Egypt with a number of Egyptian-Chinese projects, including ‘the Iconic Tower in the New Administrative Capital, the 10 Ramadan railway project, the New Alamein Towers project and the Satellite Assembly, Integration and Test Centre (AITC) which completed assembly and testing processes for EgyptSat 2 in June.’ Egypt also has a growing bilateral trade with India. As Hafez indicates,

BRICS membership would open great opportunities for Egypt, not least in terms of increasing trade and investment and protecting its political and economic interests. It would be an important step in breaking free of dollar dominance, which would boost the economy of Egypt, which imports most of its food needs. Egypt has already opened the door to dollar-free trade transactions through bilateral agreements with Russia, China and India, a step that may help promote the inclusion of the Egyptian pound in international financial transactions with BRICS countries, which are also seeking to end dollar dominance.

The United Arab Emirates is a country of seven emirates (Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Quwain, Ras Al Khaimah and Fujairah) that occupies a strategic location, possesses a massive sovereign wealth fund and follows a progressive policy of economic diversification based on the digital, circular, green Islamic economy. It has one of the highest GDP per capita rates in the world. The UAE Minister of the Economy, Abdulla Bin Touq Al Marri, was quick to point out that joining BRICS did not mean a pivot away from the US but rather represents the development of UAE’s ‘multilateralism support to the world’. He also spoke of his 7% GDP target for 2023. UAE’s attitude indicates that, as Bloomberg points out, ‘BRICS membership isn’t a hedge against the Western alliance.’ There are a variety of reasons and factors for joining BRICS by the new members, and some are driven more by economic interests than by ideology.

One measure of the significance of these countries is given by the Office of the US Trade Representative, which notes the US had $215 billion (exports/imports) in trade with MENA in 2008, ranking 4th as an export for the US in 2008. The inclusion of the 4 MENA countries is a recognition of the political, trade and investment sovereignty of a regional organisation from the richest region in the world, a region that has come of age with stronger governance and new Chinese-brokered relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia. BRICS11 now includes the largest populated countries in the world, with China and India at 1.4 billion and the largest economy (China by PPP) in a constellation underwritten by the New Development Bank that is directed at both trade and diplomacy with the capacity to help reshape the Global South as an increasingly powerful world institution. The BRICS, without the addition of MENA and Argentina, were already exceeding the G7 in terms of world population and trade, though not GDP per capita, now becomes even more formidable.

The MENA group of countries joined a joint Ministerial Conference on Governance and Competitiveness with the OECD in 2021, where it was noted in the Declaration that the region ‘has been engaged since 2005 in a process of public governance and economic reform as well as a social transformation supported by the MENA-OECD Initiative on Governance and Competitiveness for Development.’ The MENA economies started to show signs of recovery from the pandemic in 2021, with a 5.6% GDP growth in 2022 in the Middle East and 4.1% in North Africa.

Only a decade ago, the region was in turmoil, and Syria, Iraq, Libya, Yemen and Sudan are in civil war. The region faces political instability, and, also, many countries like Jordan, Lebanon, Djibouti and Tunisia face economic fragility, including a massive refugee crisis. Only a decade ago, many demonstrated in the Arab Spring to demand sweeping reforms, in some cases ending years of dictatorship. The inclusion of these MENA states is an opportunity to build on trade and development as a way forward rather than the often thinly veiled Western sponsorship propping up corrupt administrations.

The inclusion of Ethiopia as a new member is also a reminder that BRICS is not a collection of only the richest states like G7 but is directed at economic development and that BRICS represents new possibilities for development finance as well as improving investor perceptions. The new membership was described by one expert as a ‘significant diplomatic triumph’ providing ‘negotiation power for members in dealing with Bretton Woods Institutions.’ As Ramaphosa emphasised, ‘the block is an equal partnership of countries that have different views but a shared vision.’

Argentina’s inclusion in BRICS was seen by outgoing President Alberto Fernandez as an opportunity to strengthen the economy, opening up ‘possibilities of joining new markets, of consolidating existing markets, of raising investment coming in, of creating jobs and raising imports,’ especially for a country that faces a falling peso, huge inflation and repayments of an IMF $44 billion loan which is suffocating the economy. The BRICS opportunity may offer ways of defining Argentina’s debt problem, although elections in October might upend the proposed new membership with the ascension of the far-right candidate Javier Milei, who wants to substitute the US dollar for the Argentina peso.

Once the process of membership has occurred, BRICS will represent 36% of the global GDP and 47% of the world’s total population. The Western press has been almost uniformly dismissive or openly ideological, choosing to emphasise the deep divisions among the BRICS rather than the historic nature of change and the world significance of a new constellation of the Global South and world order. The historic nature of this change will not appear overnight but will come to be realised in part in the immediate future in the aftermath of the US election and the outcome of the Ukraine War, and its influence will steadily be felt as the bloc continues to take agency away from established powers in a neo-colonial world and expand its membership, its economic benefits and its political voice.