In the beginning of the pandemic the hospital began to admit a few Covid patients to the emergency department. In very little time, the Covid unit was filled to capacity. That was in March, 2020. The Covid unit then morphed into many Covid units. Not long after that, the Covid patients began spilling out into the general hospital population. By January of 2020 refrigerator trucks clandestinely parked outside of the hospital. Now, the morgues cannot handle the numbers.

In March, 2020 when I first entered the Covid unit as a hospital chaplain, I was stunned by the number of Covid patients on the floor. Room after room after room. Isolated behind glass. Machines beeping. Patients on ventilators. Medical staff –and now chaplains–wearing N-95 masks, face shields, goggles. The minute I stepped foot onto the Covid unit– garbed in PPE (personal protective equipment)—it felt as if the ground slipped from underneath my feet; I nearly fainted. Kierkegaard described fear and trembling. I felt—in a visceral way—a Kierkegaardian fear and trembling. The Covid crisis is a tectonic shift in hospital chaplaincy and in medicine generally speaking.

Hospital chaplaincy has had to undergo many changes since the arrival of Covid. Technology—and the debates about its use—became an issue. The old guard—arguing on zoom over the uses of technology—were firmly against engaging in remote chaplaincy. An elder statesman—and retired military chaplain—exclaimed that chaplains should go into the battlefield like soldiers. Solider on into the hospital. Others argued that that was too dangerous. Some hospitals do remote chaplaincy. Boots on the ground chaplains—as it were—go into hospitals regardless of the dangers.

I work at a level 1 trauma hospital in USA. We see it all. Including Covid patients. With boots on the ground, we utilize iPads, Webex and Facetime for families of Covid patients. No families are allowed on the Covid units, even when patients are dying. It is just too dangerous. But chaplains—with boots on the ground—go to the Covid units with iPads in hand. Webex is the only way families can say their goodbyes. Chaplains stand outside of glass rooms holding up iPads using Webex so families can at least see their loved ones. But the patients behind the glass do not hear, do not see. By the time the chaplain is called, patients are nearing death. Most of the Covid patients are unconscious and on ventilators. Multitudinous machines—to which patients are attached– make Covid all the more ominous. Chaplains increasingly are called “angels of death.” We arrive at the final moments of a patient’s life, standing outside of glass windows holding up iPads using Webex technology so that families can say their final goodbyes.

Technology

Technology—the dialectical dilemma about which Walter Benjamin wrote—can serve both productive and destructive ends. Benjamin thinking about telephones and radio, warned that although these technologies could be used in productive ways, they could also serve to dehumanize. How prescient he was. Benjamin wrote about technology decades ago—and realized the complexities and dialectic that technologies presented.

In hospitals—especially on Covid units– Webex, or Facetime, iPads and cell phones facilitate final goodbyes. Seeing loved ones for the last time and being able to say goodbye—is a kind of ritual. Rituals matter. Goodbyes matter. At least for some. But for others, the visual, the image– the grotesque images–of loved ones hooked up to machines makes things worse. Sometimes families want to see their loved ones because they do not believe Covid is real. When doctors break the bad news to families that their loved ones are dying from Covid, families sometimes do not believe what they are hearing. Part of this is psychological denial. Another part of this is cultural denial. The idea that Covid is a hoax permeates American culture. Even when families see loved ones hooked up to machines on the Covid unit—via Webex– they still do not believe Covid is real. Seeing and believing do not necessarily coincide. Others, however, are shocked at what they see. And perhaps they regret seeing what they see. The horrors of Covid through Webex, shock. Some are stunned into silence by what they see.

Chaplain Kristin Michealsen leaves a covid unit after talking to a family member of a deceased patient. (Jae C. Hong/AP)

It is a difficult moment for the chaplain too. Picking up the pieces of a shattered family is no easy task. Like shards of glass, families are broken, destroyed. Chaplains are there to be-there. Being present with the families—even if only on Webex on an iPad—serves as a kind of Winnicottian holding. But still. That is never enough. Covid devastates families. More often than not, after one family member gets sick, the others follow. Terrible endings. Chaplains, or “angels of death,” engage in a necessary and terrible vocation. At the end of a life, chaplains are the only ones present with the families. The medical team has to move on to the next Covid patient, the next trauma, the next horror. This vocation calls.

Psalm 23: Shattering Memory

A patient behind glass windows, machines beeping. An outtake. A memory can shatter time, as Walter Benjamin might put it. The memories that shatter time are like outtakes in a stream of consciousness; these are the memories that stand out. These are the memories that haunt. This is the story of a memory shattered. This is the story of a chaplain reciting Psalm 23 in the emptiness of the Covid ward.

The numbers on the monitors are dropping quickly. No family present. No medical staff visible in the long empty hallway. I was alone. Standing behind glass in front of a dying man hooked up to machines. I opened my tiny pocket Bible that I carry with me on rounds and proceeded to recite Psalm 23 out loud. But no one heard me. No one present. Not one nurse; not one doctor. Not one family member. This dying man could not hear me, nor could he see me. He was unconscious; he was dying. I recited the words deliberately, slowly. The family had requested a final prayer. This was the prayer I recited. Psalm 23.

Kierkegaard writes much about the Biblical story of Abraham because Abraham signifies what Kierkegaard called the “knight of faith.” Faith sustains in the face of hopelessness. Yet, I do not know what this means, existentially. Faith in what? Faith for what? What is faith? I do not even understand this concept.

Cliches like keep the faith, or have faith, or take the leap of faith make little sense to me. Cliches are the equivalent of what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called cheap grace. There is nothing cheap about the sanctity of death. Cliches around death trouble. Death is not a cliché. I have been there at the moment of death for hundreds of patients and their families. There is a sanctity about death. Words should not serve to gloss over that moment when a life, a spark, is gone. Chaplaincy—at the moment of death—is the discipline of silence. There is something so difficult about being silent, remaining silent, allowing the silence to speak. At the moment of death my vocation as a chaplain means dwelling in silence. The moment of death is not a moment for cliches or idle chatter. The Balm of Gilead is the equivalent of cheap grace. Presence-in-absence is the heart of my chaplaincy.

I recited Psalm 23 out loud in the emptiness of time and space, the loneliness of death. I cannot speak the dying man’s name; nameless he will be. But the dying man is not faceless. The Face of God is in the Other, Levinas teaches. The dying man is that Face of God. The chaplain faces the Face of God in death. Thomas Merton wrote that God is silent. You will not hear God anywhere at any time. If you look for God you will not find anything. Merton wrote that God is silence.

The dying man is etched in my memory; he is archived in this act of writing. Writing is a vocation like chaplaincy. One is called to write; in the spirit of Levinas, writing is an ethical responsibility. To respond to both the living and the dead is the vocation of the chaplain. Let us etch this dead man’s memory—into the parchment of the archive; into the parchment of time.

Let this be a testimony to the dying and the dead, to the forgotten and alone, to the grieving and aggrieved. I finished reciting Psalm 23, closed my tiny pocket Bible and paused. I paused. I waited. I waited some more. I am witness to an unspeakable horror. Covid is that horror. When called, I continue to recite Psalm 23 in front of a looking glass darkly. “Even though I walk through the shadow of the valley of death”–the Psalmist wrote. The shadow of death hovers over all of us. The shadow of death is the philosopher’s stone.

Let this be a testimony to the dying and the dead, to the forgotten and alone, to the grieving and aggrieved. I finished reciting Psalm 23, closed my tiny pocket Bible and paused. I paused. I waited. I waited some more. I am witness to an unspeakable horror. Covid is that horror. When called, I continue to recite Psalm 23 in front of a looking glass darkly. “Even though I walk through the shadow of the valley of death”–the Psalmist wrote. The shadow of death hovers over all of us. The shadow of death is the philosopher’s stone.

Hospital chaplains, like psychoanalysts, mirror back to families what it is that sustains them. Chaplains take care of those who are suffering. Chaplains take care of those who come into our care. I have taken care of lawyers, judges, teachers, criminals, murderers. I have taken care of Republicans, Democrats, autocrats, bureaucrats. I have taken care of Catholics, Pentecostals, Baptists, Muslims, Hindus, Jews, fundamentalists, atheists, Episcopalians, agnostics, Presbyterians. I have taken care of transgender, queer, straight, nonbinary, bisexual patients. I have taken care of patients who are black and brown, some who are white, some who are wealthy, some poor, the homeless. I have taken care of schizophrenics, psychotics, alcoholics, those addicted to drugs. I have taken care of victims of gun shot wounds, stab wounds. I have taken care of patients suffering from cancer, amputation, strokes. I have taken care of patients who have committed infanticide, matricide, patricide, homicide. I have taken care of those left behind after someone died by suicide. If this sounds like Greek tragedy, it is. Greek myths are not merely stories of old. Greek tragedy is real.

Philosophy, theology, psychoanalysis—these disciplines I have spent a lifetime studying. But none of them have prepared me for the horrors of Covid. I have been doing chaplaincy work for about four years and have never seen anything like what we are witnessing with Covid. So much death, so much terrible, unnecessary death, such suffering. Nothing in my rigorous chaplaincy training—which is both clinical and theoretical– readied me for the crisis of Covid.

I once read that Bruno Bettelheim, a psychoanalyst, who became well known for his work on fairytales-as-pedagogy, if you will, reported (while he was in a concentration camp during the Holocaust) that no amount of psychoanalytic training readied him for what he witnessed in the camps. None of his learnedness helped him to understand the incomprehensible. What I am witness to—with the Covid crisis—is the incomprehensible as well. It is the unnecessary deaths, the avoidable deaths, that pains. Four hundred and fifty thousand Americans did not have to die like this. Four hundred and fifty thousand Americans die alone, behind a looking glass darkly. This did not have to happen. And yet it did. And now we are faced with a tragedy so massive that none of us can cope with it. And yet, like a Beckettian play, we move on and yet we cannot, we keep going and yet we cannot.

Hannah Arendt once coined the phrase the “banality of evil.” She coined this term in the midst of the Holocaust; in the midst of the horrors of Nazi atrocities. The everydayness of it—the banality of atrocity–is what struck Arendt. Holocaust Historians—only just in the 1980s—began to write about the complicity of “everyday Germans.” The phrase “everyday Germans” is a trope for Arendt’s “banality of evil.” Everyday people are capable of doing everyday evil.

Ten months into the Covid pandemic I have witnessed what I call the banality of Covid. Covid is the evil. Covid is the enemy. Covid is the atrocity. Covid doesn’t wear a brown shirt, or an SS insignia. Covid is invisible. It is everywhere, it floats in the air. And it is deadly. Covid cares not. Covid does what it wants. Covid kills. Continual mutations are getting more deadly, in fact. This is a war against the invisible.

When chaplains are called it has become a like a battlefield. The hospital has become a war zone. The stories from the hospital zone—some report—are not unlike what soldiers report after being traumatized from war. There will be battle scars, shell shock—as Freud called it. At this point in time, front line medical staff face psychological unknowns. The Covid crisis is daunting. Hospitals are at capacity, over capacity. ICUs are full. There is no more room.

Covid Collateral

Covid collateral is real. The phenomenon I call Covid collateral has also surfaced like Greek tragedy. Drug overdoses, suicides, homicides and domestic violence have increased tenfold since Covid emerged. The murder rate in my small town is out of control. However, the why’s of murder cannot be reduced to economic issues, although violence is symptomatic of the stress of losing jobs, losing homes and going hungry. There is more to it than that. The Frankfurt School scholars studied the why’s of violence during the 1930s and 1940s. But they came up short. Historians, psychologists, psychoanalysts, philosophers, political theorists, criminologists have come to little consensus on the why’s of murder.

The question that is so puzzling today is that Covid collateral—like collateral during times of war—is a little talked about phenomenon. During war, allies fight axis powers. There are rules of engagement during war. One of these—at least during the world wars—was avoid civilian casualties. But it seems there are always civilian casualties. These civilian casualties are wartime collateral. Crimes against humanity are committed against innocent civilians. These crimes should be tried in the Hague. Eichmann was tried in the Hague. He was a war criminal. Countless examples of war criminals could be named here.

War, Politics and Covid Collateral

Pacifists claim that war is always wrong. Killing is wrong. However, there are just wars, sometimes revolutions are necessary. Albert Camus drew a wedge between revolt and revolution. Frantz Fanon, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir felt strongly that revolutions are necessary to fight social injustices when discussion and debate is no longer a viable option.

There are just revolutions and there are unjust revolutions. China’s revolution under Mao was an unjust revolution. Patriot education under Mao and re-education under Mao was a code for torturing or killing teachers who disagreed with Mao. Patriot education—what Trumpists want in the United States—horrifies. Patriot education is code for racism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism and obedience to the state.

I raise these issues against the backdrop of Covid because all of this, from civilian casualties to patriot education, from racism to xenophobia, from revolt to revolution are all relevant to Covid. The collision of Covid and totalitarianism is no accident. What better way to instill obedience and subservience, fear mongering and hatred—while disease takes its toll and is allowed to get worse. Medical professionals silenced, professors silenced, teachers punished. Under Trumpism, we have witnessed the rise of totalitarianism and fear for the future. The longing for a leader who has all the answers, the cult of personality is made only stronger especially during a plague. The country already in chaos, no answers at hand, is ripe for dictatorship. All of this, too, is Covid collateral.

Democratization

Jacques Derrida reminds us that democracy is to-come. It has not yet arrived. Democracy-to-come means that health care must also be democratized. However, health care in the United States is not democratized. As long as insurance companies are making profits, those without the capital will pay—and sometimes they will pay with their lives. Not everyone gets the same medical treatment. A person suffering from blood cancer needs treatment that costs hundreds of thousands of dollars. Without insurance, these people will not get the treatment that they need to survive. Simply put, they will die. Judith Butler writes about the evils of neglect. Those left to die—the medically neglected– lack capital.

Without the capital, Cancer and Covid can kill. Cancer patients—especially those undergoing chemotherapy—are much more vulnerable because they are immunocompromised by chemotherapy. Those who would have survived—because of chemotherapy—might die because of Covid. This is another kind of Covid collateral. In fact, any immunocompromised disease puts people at higher risk for dying from Covid.

Chaplaincy has become more complicated because of Covid collateral. The hospital feels like a chaotic war zone. It is worse in big cities. I live in a small town, at least that is how I think about it. I work at a rather large hospital, but not nearly as large as say Johns Hopkins. Covid collateral has radically changed a day in the life of a chaplain. Before Covid I would be on the floor for a few hours—as I am on call—and go home. Since Covid my hours keep getting longer and longer. Now, I am working sometimes as long as the medical staff. Some days are thirteen hours long. This, as I see it, is due to Covid collateral. People are living on the edge. And many fall off the edge. Some we can catch. Others fall forever—as Winnicott might put it. Falling forever—psychologically—is the result of living in a universe out of joint. Yes, time is out of joint. Covid has put us all out of joint.

Silence

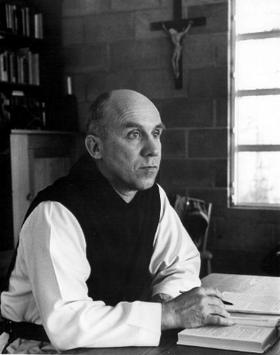

Thomas Merton – Trappist Monk 1915-1968

Unlike the professorate, chaplaincy is not about pedagogy, we do not teach. Patients, rather, are our teachers. Unlike the priesthood, chaplaincy is not about preaching. Thomas Merton—a Trappist monk—preached silence. Trappists do not speak. Their vow is that of silence. Thomas Merton has been my teacher. From Merton, I have learned the art of silence.