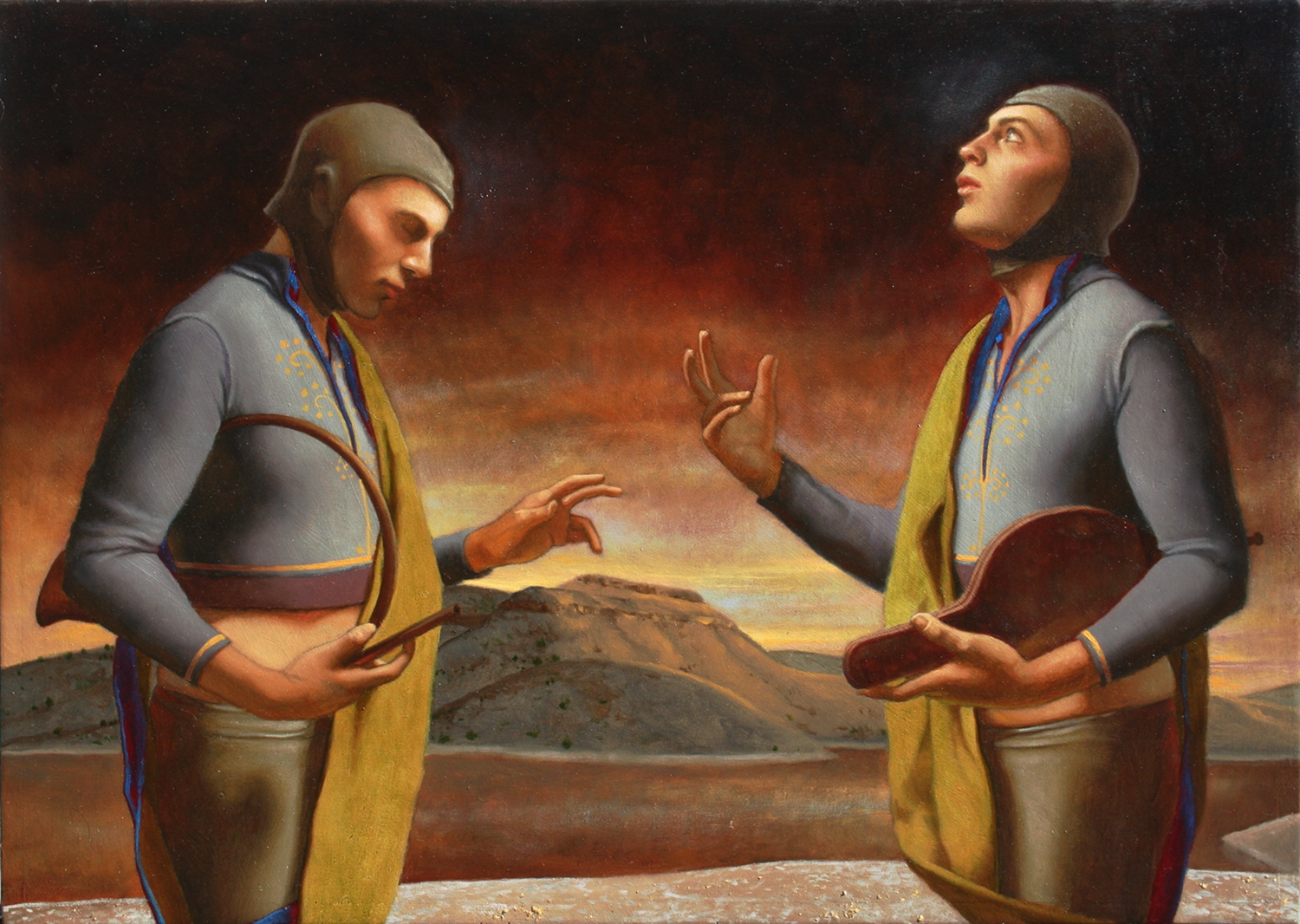

Chris Sedgwick, The Past Meeting The Future, 2014. 10.25″ x 14.5″. Oil, gold leaf on birch

Andrei Tarkovsky, Russian filmmaker, shot seven films. His best-known films are perhaps Solaris and The Stalker. His lesser-known films such as Nostalgia – filmed in Italy – Andrei Rublev and others such as The Sacrifice – filmed in Sweden – are less well known. After shooting the film Nostalgia, Tarkovsky never returned to Russia. He intimates that Russian authorities exiled him because of the controversial nature of his films. Ingmar Bergman – well known for his films such as Fanny and Alexander, The Seventh Seal and Winter Light – considered Tarkovsky the greatest filmmaker of all time. I would concur. Bergman’s films are perhaps better known than Tarkovsky’s because they are more accessible.

Tarkovsky’s films are less accessible, perhaps because of their bizarre nature – interestingly, though, Berman’s influence on Tarkovsky is ever-present. Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice struck me as his most moving, deeply bewildering and disturbing. Not only is the film stunning artistically, it is eerily relevant against the backdrop of COVID-19 pandemic. The viewer cannot think her way – rationally – through the film because it belies reason and sense. Tarkovsky deliberately confuses images, times, scenes. Altered time, altered perception immerse the viewer into a strange, eerie world. The film takes hold of psyche; it is about nuclear apocalypse: a terrifying vision of the end of the world. Tarkovsky is obsessed with the end of the world and death – as evidenced in his other films as well.

Like Ingmar Bergman, Tarkovsky draws upon similar themes such as anxiety, dread, terror, slowness, the eternal ticking of clocks, mirrors, dripping water and slowness. There tends to be an alienation between the characters in his films – nobody seems to be connected to anybody, people generally do not like one another; characters put up with one another or are totally isolated in their strange worlds.

Tarkovsky opens the film The Sacrifice with an old man and a child attempting to fortify a dead tree. A postman, riding a Beckettian bicycle, pontificates on Nietzsche’s theory of eternal recurrence. Viewers learn that the old man is a retired academic who has been fascinated with Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence for some time. The old man-academic and the child, called ‘the little man’ – symbolize, to me, the circle of life and death, the old with the young, death and rebirth. The last scene in the film focuses on the child under the same dead tree as the old man is driven off in an ambulance because he has lost his mind after setting his house ablaze believing that he is saving humanity from the end of the world by doing so. He, thus, sacrifices his home and family, to save the world. It is only he who can stop the nuclear apocalypse through this sacrifice – or so he thinks.

While Tarkovsky was shooting The Sacrifice, he knew that he was dying of cancer. The theme of waiting – very much like Beckett’s Waiting for Godot – might be a reflection of his own waiting to die from cancer and all of the horror that goes along with the not knowing, getting sick, the fear, anxiety and dread that also go along with the dying process. The gravity of the film begins with two juxtaposing images: Leonardo Da Vinci’s painting Adoration of the King and Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew’s Passion playing while the camera slowly pans over the Da Vinci’s painting. The significance of this juxtaposition is this: The Adoration of the King concerns the birth of Christ while Bach’s oratorio concerns the crucified Christ, the dying God, death and resurrection. Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence: the circle of life and death, the birth and death of Christ. This is a foreshadowing of the opening scene of the old man and the child attempting to fortify a dead tree juxtaposed with the final scene in the film of the child under the same tree, while the old man is whisked away in an ambulance, gone mad, setting his house ablaze believing that he made the greatest sacrifice for the survival of humankind. Christ’s crucifixion, death and resurrection are thought to be the sacrifice God made of his only begotten son in order to save the Christian world from sin. On yet another level, Tarkovsky dedicates the film to his son – in the end credits – with the hope that his work gives his son courage. The old man, the child and a life dedicated to film, a legacy to leave behind is the sacrifice. Tarkovsky’s filmmaking, too, is his artistic sacrifice he made not only to the world but to his son. Against Soviet persecution of Christians, Tarkovsky prevailed exiled.

What is striking about this particular film – and Tarkovsky’s work in general – is that he engages in a deeply Kierkegaardian Christianity. By this I mean, Tarkovsky – like Soren Kierkegaard, the existential philosopher from Copenhagen who lived during the late 19th century – did not engage in false piety, nor did he sanitize his imagery. This is not watered – down faith or what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called cheap grace. No, Tarkovsky engaged in a cinematographic-immersion in the deeply theological, the deeply philosophical, or what the Nietzsche – who as an atheist – called ‘the greatest weight.’ Flannery O’Connor’s characters in her American fiction were full of false piety and cheap grace. She knew that this kind of religiosity was false and yet very common for Sunday church goers, especially in the South (in the United States). Hypocritical, false piety was repugnant to O’Connor, especially because she was Catholic-Christian and felt that faith should be otherwise.

One of the other striking things about Tarkovsky’s film – especially The Sacrifice – is that the viewer is immersed in an experience as-if watching paintings-in-motion. All of his work is as-if the viewer is immersed in slowly moving paintings. Colours, hues, shades, artfully done poses, characters crafted as- if out of a Da Vinci painting. Amidst the themes of death and dying, dread and anxiety, there is a certain sublime quality to Tarkovsky’s work. The films are, in fact, so slow-moving, that they are, in a way, painful to watch. But from that pain comes such depth of feeling, colour, shading and even beauty, stunning artistic performances and cinematography unlike any other cinema I have ever seen.

Connections to the Paintings of Chris Sedgwick

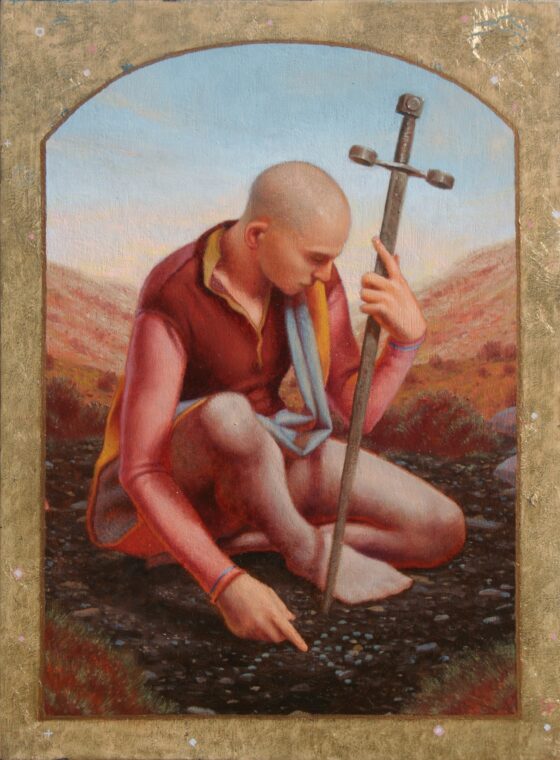

Chris Sedgwick, Passing of the Ages, 2013, 10″ x 14.5″. Oil, gold leaf, mica on birch.

Fleeing a hurricane from Savannah, Georgia I happened upon a hotel in Ashville, North Carolina. The hotel – artfully done – is one of many Richard Kessler hotels built especially in the American South. I stay in Kessler hotels because they are rich with colour, depth and even a sense of deeply felt spirituality. Upon arrival to my room, I noticed some paintings outside my room on the wall. I was stunned as I walked past. The paintings stopped me in my tracks because they were rather strange, bizarre, haunting. I enquired at the front desk about the paintings and they told me that the paintings had been commissioned by the hotel and that they were by painter Chris Sedgwick. On the flight home from Ashville back to Savannah, I was haunted by Sedgwick’s paintings. Once arriving back home, I looked up his work on the internet and found his website. I contacted Sedgwick and commissioned him to do a small painting for me. Over time, I commissioned him to do three more small paintings as well.

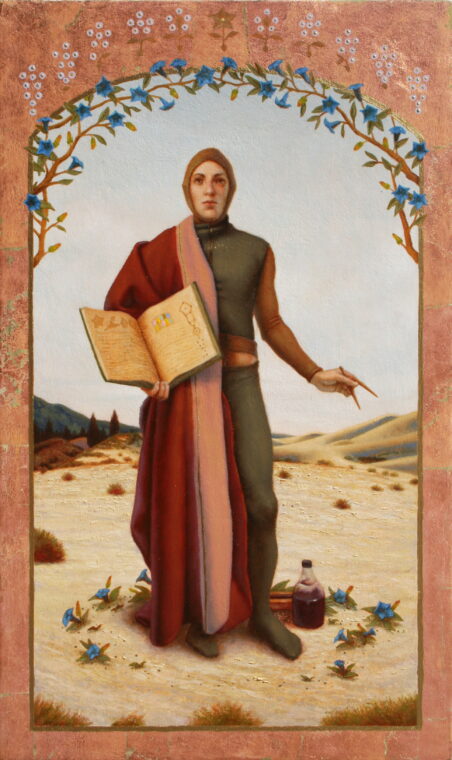

Strangely, Sedgwick’s paintings parallel the work of Tarkovsky. I asked Sedgwick if he had seen Tarkovsky’s films – recently – and he said that he was not familiar with them. Sedgwick’s work, like Tarkovsky’s, is deeply theological, philosophical, stunning in colours and depths and strange. It is the strangeness of both Sedgwick and Tarkovsky that make me think of them together. Ironically, Sedgwick’s paintings are as-if cinematography, each telling a bizarre story in some other worldly place that one cannot quite figure out. They mix time, scene, ancient, alchemical, modern, monastic and yet modern in their oddness. I inquired as to the influences in Sedgwick’s work and learned that he has studied alchemical engravings such as J. D. Myllus ‘Macrocosm Basilicae Philosophica’ from Opus Medico-Chymicum, dating back to the 17th century. Sedgwick is interested in philosophical theology of the Rosicrucians, especially as represented by one J. Augustus Knapp, an early 20th-century artist. Researching the Rosicrucians, I discovered that they can be traced back to 1500 BCE, Egypt; they were the earliest mystery cults, later becoming gnostic traditions. From Egypt, the mystery cults evolved and were re-conceived through Greek ancient philosophers, influencing, in some sense, the Kabala (ancient Jewish mysticism), and Christian mysticism and alchemy – the magic of turning base metals into gold. Rosicrucians relocated and moved to the United States and Europe. In the 20th century, the Rosicrucians came to New York and California. The term Rosicrucians roughly means rose and cross, which ‘represent the experiences and challenges of a thoughtful life well lived’ (see, Rosicrucian.org. ‘The Ancient and Mystical Order Rosae Crucis’). The Rosicrucians, today, attend meetings, have websites and even an online peer-reviewed journal called Rose Croix Journal. This journal is interested in writings blending spirituality, the arts, mysticism, science and history. The journal is much like the idea of Renaissance scholarship – where the divisions between disciplines had been broken through and broken down. Likewise, science, art and mysticism – for Rosicrucians – fuse.

In Christianity, Gnosticism got exiled from mainstream tradition because of esoteric beliefs; likewise Christian women mystics were thought to be too radical for mainstream Christianity, while mainstream Judaism paid the mystic book the Kabbala little mind: it is still considered by many Jews an esoteric, irrelevant book.

Matthew Fox, the former Catholic Priest who was ousted from the Church for claiming that people are not born sinful, but rather, from what he called an ‘original blessing,’ uses terms like ‘cosmic consciousness,’ which the Rosicruicians use today. Fox, now an Episcopalian priest, has more freedom to write as he pleases: freedom of expression is not something the Catholic church cherishes. One of the reasons that Catholic theology has lagged behind Protestant theology – historically – is because theologians – who are priests, nuns, monks, friars and so forth – have to align their work with Papal dogma. This becomes problematic for academic priests and nuns.

Chris Sedgwick, In the Wilderness, 2015, 12″ x 9″. Oil, gold leaf on birch.

It seems that mysticism – in whatever tradition to which it belongs – has historically been marginalized because one does not need a church, a synagogue, a Mosque, a Shrine, a temple or organized religion to participate. This has always been seen as a threat to religious authorities because without an institutionalized Church, for example, one doesn’t need to obey mandates or rules of order like the Benedictine Monks, for example, who follow a strict book of rules dictating what they read and basically what they do every minute of the day. Friars are freer to float around without being confined to a monastic community, but still they are bound by the rules of the church.

Mystical Heretical Philosophical-Theology: Sedgwick and Tarkovsky

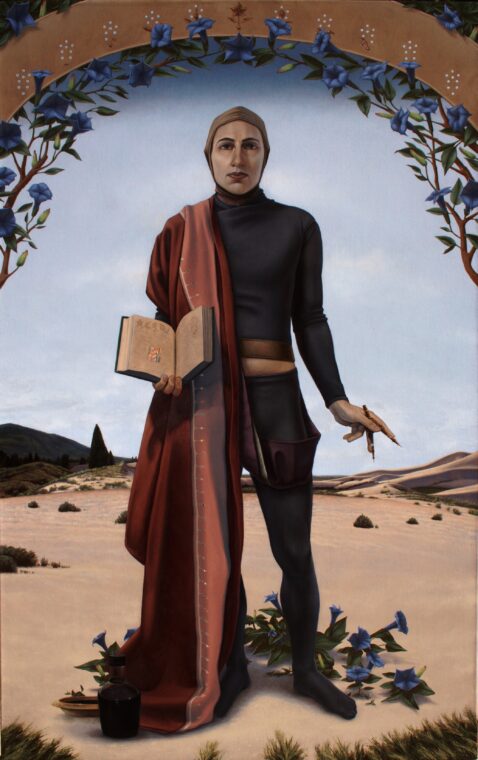

Chris Sedgwick, The Geometer, 2011, 60″ x 37″. Oil on canvas.

The connection between painter Chris Sedgwick’s unorthodox and – some might say – esoteric painting and filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s deep theological unorthodoxy draws me in because of their mystical, heretical philosophical-theology. Tarkovsky holds onto a deeply theological Kierkegaardian Christian mysticism that was, in part, what got him exiled from Soviet Russia. Communism – at least in Soviet fashion – did not tolerate religiosity of whatever kind. Sedgwick’s mysticism is reminiscent of Tarkovsky.

Chris Sedgwick, The Geometer, 2018, 16.75″ x 10″. Oil, copper leaf on birch.

Cinema and Paintings during the Age of COVID-19

Trained as a musician, a classical pianist to be exact, I have always had a great love for the arts. Being an academic is a challenge for me because I do not quite fit into any genre or field. I am inter-disciplinary and have studied everything from philosophy to religious studies, from American education to European history. I have a love for cinema and painting, in particular, but am not, in any way, learned in either of these areas.

Writing has always been a passion of mine but it does not come easy for me. My most native intuition comes before language, or the pre-verbal, in music, especially. This is perhaps why I am drawn to other art forms such as cinema and painting. The ear, the eye, intuition and the mystical have been more my kin than words. Academic papers are very difficult for me; they come after many revisions and re-edits and more drafts and more drafts.

There is a line in Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice, where the old man says ‘words, words, words,’ implying: what do they mean in the face of death, dying, the end of the world, or the end of one’s world?

Words are magic when they work and when they are crafted like art, but when used in utilitarian ways, or ways the box truth into rubrics and standardized narratives – I find completely troubling. In fact, words – especially medical narratives boxed into rubrics, and standardized language – do not help unpack the complexities of COVID-19. This disease has no logical trajectory and a continually, confusing, changing genomic structure that scientists are having difficulties grasping.

When I woke up one day feeling very sick, I knew right away that I had COVID-19. I was careful, wore N-95 masks, face shields, goggles. It still didn’t save me from the horrors-to-come. Being a cancer survivor and going through very difficult chemotherapy did not help me either.

Tarkovsky was dying of cancer while he shot the film The Sacrifice. He knew he was dying. When faced with mortality, life’s projects become even more urgent. The seriousness of the cancer I suffered through in 2016 – ovarian cancer – the one women do not want to get – put me face-to-face with the prospect of dying. Living through chemo was everyday torture, certainly beyond words. 2020 arrives. Now, struck down with COVID-19, the horrors of living again with the possibility of dying, especially having had a serious form of cancer and chemotherapy with possible developments of secondary cancer later in my life – brought it all home again. When faced with one’s mortality, life’s work becomes urgent. One asks oneself: what is my work? What am I supposed to be doing?

For Tarkovsky, his task was to finish his filmmaking with his final testimony, as he called it, in The Sacrifice. I was memorized by feeling immersed in his film; this strange immersion gave me something to hold onto artistically while my hopes began to wane about my very survival. Nights were filled with terrors of dying. Nobody has answers. COVID-19 takes its own bizarre twists and turns. Symptoms emerge that are quite bizarre. Two months in, and still not well. I held on to Tarkovsky’s visions and images as artistic relief and relation – as bizarre as his films are – I somehow relate, theologically, philosophically and spiritually. His films are not cheap grace, not false piety: cinema as art, not Disneyfied.

Likewise, Chris Sedgwick’s paintings – which remind me of Tarkovsky’s work being immersed deeply theologically; heretical images of life and death – have given me great solace in a time of deep concern, worry, anxiety and fear. When illness overtakes my personal world, I hold onto what I most relate to: the pre-verbal, images, sounds, cinema, paintings, music. And then I write. Words, although secondary for me, also provide some solace and even therapy; to express fears, anxiety, grief and longings through language is a form of therapy. Freud once said that if one struggles from problems, writing them out continuously is a help. Freud also said once that he could not write meaningfully without pain. He was literally pained from suffering from cancer of the jaw, but he was also pained by what was happening around him in Austria after the Anschluss (the German occupation of Austria) and the anti-Semitism that he and his family had to suffer through until he and his daughter Anna fled to England. It is a little-known fact among American intellectuals that Freud’s three sisters were murdered in the Holocaust.

Against the horrors of COVID-19, in the United States – and perhaps all over the globe – anti-Semitism is on the rise once again. Holocaust scholars have argued that anti-Semitism, as well as racism(s) in their various forms, never really go away; they just go underground and re-emerge as Pandora’s box opens through the rise of authoritarianism and dictatorships. The collision of authoritarianism, the pandemic, racism(s) and anti-Semitism is not coincidental. I never thought that I would live through the likes of either a global pandemic or the rise of dictatorship right here on my home soil, in the United States. Pandora’s box of hatreds has been opened with this wretched post-Truth Trumpism. The question is, how do we close the box after this mess is all over? Or can we?

I am not a political scholar per se, but I have a keen interest in political history and the rise of authoritarianism(s) since the turn of the 20th century. And now politics has come directly to my doorstep. My illness is a direct relation to a Republican administration who cares little for human life, while only capitalist greed drives overly zealous authoritarianism. It is no accident that I got sick in a state where we have a Trump sycophant for a governor, who then turns his power to trustees and boards that control state institutions and public policy. Politics has come to my front door. The pandemic and over 222,000 deaths in the United States are directly related to authoritarianism, racism(s), and xenophobia.

For me, a saving grace has been the arts: cinema and painting. Wittgenstein said that certain language games have family resemblances. Artists, too, can be connected through strange kinships. A young American painter named Chris Sedgwick and a world-renowned filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, could not be more different – and yet both strike a chord of resemblance in me. Sedgwick, not familiar with Tarkovsky share an almost alchemical synchrony, as Carl Jung might say. Immersion in Tarkovsky’s cinema, surrounded by Sedgwick’s painting in my study, has sustained me through this illness.