[This is an experiment that takes a series of related tweets (in italics) and amplifies them through a series of fragments from the scholarly literature … and philosophical journalism. N.B. Twitter can be used to think philosophically! (Ed.)]

I. There is room and a need for academic or philosophical journalism that records and reflects on the nature of current events, especially in an interconnected and complex world environment. For traditional academic work, be prepared to wait eighteen months for it to appear. This means philosophy always lags behind current events.

- Philosophy can seem remote from day-to-day news coverage, but I’ve always tried to introduce philosophical ideas, or at least reference to philosophical thinkers, where possible in writing for The Irish Times. This took on a more formal shape on World Philosophy Day 2013 when I started the weekly ‘Unthinkable’ column – a kind of philosophers’ corner – where I would ask a thinker or author to advance an ‘idea of significance,’ which I would then attempt to interrogate. (Joe Humphreys, https://blog.apaonline.org/2017/01/18/philosophical-journalism-interview-with-joe-humphreys-at-the-irish-times/)

- Loyn advocates a rather old-fashioned sounding role for the journalist. News is what’s happening, and we should report it with imagination and scepticism (where appropriate). He wants journalists to be objective and tell the truth. The cognoscenti must have choked on their sun-blush tomato ciabattas. (Julian Baggini, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/article_1218jsp/)

- In the so-called ‘Post-Truth’ age, when some segments of the population doubt the credibility of the legacy press and are therefore susceptible to the untruths spread by both President Trump and unscrupulous partisan websites, journalists will have to work harder to breakdown the existing barrier of civilian distrust in order to counteract these inventions with factual reporting. (Guillaume A.W. Attia, https://medium.com/@gawattia/how-philosophy-can-make-journalism-better-92a381ec632)

- ‘We Need “Philosophy of Journalism.”’ (Carlin Romero, https://www.chronicle.com/article/we-need-philosophy-of-journalism/)

- Journalists, journalism scholars and philosophers have long noted a dearth of engagement between journalism and philosophy, particularly in the Anglophone world. Yet, they have much to gain from each other as professional communities and as disciplines of thought and practice. (Christopher Schwartz, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1889397)

- Post-Truth & Fake News: Viral Modernity and Higher Education: The editors and authors argue that notions such as ‘fact’ and ‘evidence’ in a post-truth era must be understood not only politically, but also socially and epistemically. The essays philosophically examine the post-truth environment and its impact on education with respect to our most basic ideas of what universities, research and education are or should be. (Michael A. Peters, Sharon Rider, Mats Hyvönen and Tina Besley, https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-10-8013-5)

II. Hannah Arendt provides a good model of philosophical journalism, especially in some of her work on politics.

- Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) was one of the most influential political philosophers of the twentieth century. Born into a German-Jewish family, she was forced to leave Germany in 1933 and lived in Paris for the next eight years, working for a number of Jewish refugee organisations. In 1941 she immigrated to the United States and soon became part of a lively intellectual circle in New York. She held a number of academic positions at various American universities until her death in 1975. (Maurizio Passerin d’Entreves, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/arendt/)

- For Arendt, the public sphere comprises two distinct but interrelated dimensions. The first is the space of appearance, a space of political freedom and equality which comes into being whenever citizens act in concert through the medium of speech and persuasion. The second is the common world, a shared and public world of human artifacts, institutions and settings which separate us from nature and which provide a relatively permanent and durable context for our activities. (Maurizio Passerin d’Entreves, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/arendt/)

- As a journalist, I observed and analysed people in action, practising politics. Thoughtful action, unfortunately, appeared to be relegated by politicians to a second-tier luxury activity. As a student of political philosophy, I would characterise this as a retreat from reality to the ivory tower, in which politics is theoretical and practice, or action, is secondary (Catherine Chappell, https://dlib.bc.edu/islandora/object/bc-ir:101882/datastream/PDF/view).

III. The Arendt model of philosophical journalism using a contemporary event as a basis for ethical reflection and historical analysis; witness Arendt’s 1967 essay ‘Truth and Politics,’ reflecting on Watergate. What were its essential features?

- The question with which Arendt engages most frequently is the nature of politics and the political life, as distinct from other domains of human activity. Arendt’s work, if it can be said to do any one thing, essentially undertakes a reconstruction of the nature of political existence. (Majid Yar, https://iep.utm.edu/hannah-arendt/)

- She never wrote anything that would represent a systematic political philosophy, a philosophy in which a single central argument is expounded and expanded upon in a sequence of works. Rather, her writings cover many and diverse topics, spanning issues such as totalitarianism, revolution, the nature of freedom, the faculties of ‘thinking’ and ‘judging,’ the history of political thought, and so on. (Majid Yar, https://iep.utm.edu/hannah-arendt/)

- She lived through what she called ‘dark times,’ whose history reads like a tale of horrors in which everything taken for granted turns into its opposite. The sudden unreliability of her native land and the unanticipated peril of having been born a Jew were the conditions under which Arendt first thought politically, a task for which she was neither inclined by nature nor prepared by education. (Jerome Koh, https://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/0103/arendt.html)

- While the problem of ‘truth and politics’ is found everywhere in Arendt’s writings, there are three related texts in which it most explicitly features:

- ‘Truth and Politics,’ published in 1967, but occasioned by the reaction to Arendt’s report on the Eichmann trial in 1961 (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1967/02/25/truth-and-politics)

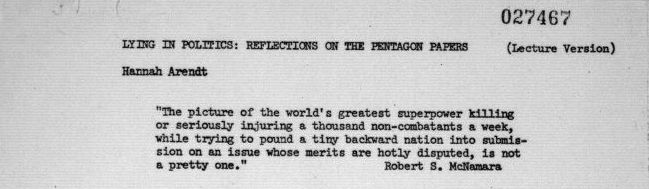

- ‘Lying in Politics,’ which responded to the Pentagon Papers and the Vietnam War in 1971 (https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1971/11/18/lying-in-politics-reflections-on-the-pentagon-pape/), and finally,

- ‘Home to Roost,’ published in theNew York Review of Books in 1975.(https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1975/06/26/home-to-roost-a-bicentennial-address/) (Benjamin Lewis Robinson, https://www.hannaharendt.net/index.php/han/article/view/406/616)

IV. Arendt’s perceptive assessment on the history of the lie in political culture: ‘the lie did not creep into politics by some accident of human sinfulness; moral outrage, for this reason alone, is not likely to make it disappear.’ A viable model of philosophical journalism.

- In an age of alternative facts, fact-checking has become almost second nature to critical thinkers who are concerned with the consequences of post-truth for the future of democracy. Drawing primarily on the work of Hannah Arendt and secondarily on that of Michel Foucault, this essay questions fact-checking as a democratic world-building practice and argues for forms of truth-telling that do not fall prey to Western philosophical conceptions of absolute truth and its hostility to plurality, opinion, and contingency. (Linda M. G. Zerilli, https://www.genealogy-critique.net/article/id/7075/)

- ‘The History and Practice of Lying in Public Life’: This paper provides an introduction to the history and practice of lying in public life. The paper argues that such an approach is required to balance the emphasis on truth and truth-telling. Truth and lies, truth-telling and the practice of lying are concepts of binary opposition that help define one another. The paper reviews Foucault’s work on truth-telling before analysing the ‘culture of lying’ and its relation to public life by focusing on Arendt’s work. (Michael A. Peters, https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/9551)

- ‘I am encouraged to think of lying as a set of cultural practices partly through the influence of Foucault’s genealogy [and] Wittgenstein’s (1953) language-game analysis[.…] ‘Lying is a language-game that needs to be learned like any other one’ ( 249). (Michael A. Peters, https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/9551)

- Arendt’s article consists in a series of reflections on the Pentagon Papers, and she bases her assessment on the history of the lie in political culture. In ‘Truth and Politics’ (1967) and ‘Lying in Politics’ (1971), Arendt reflects the fundamental relationship between lying and politics. She explains the nature of political action in the context of lying with surprising consequences that run against modern intuitions and threatens to change our understanding of the history of politics. (Michael A. Peters, https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/9551)

- In ‘Lying in Politics,’ Arendt provides an account of political imagination that draws interconnections between ‘the ability to lie, the deliberate denial of factual truth, and the capacity to change facts, the ability to act.’ (Michael A. Peters, https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/9551)

V. ‘The deliberate falsehood and the outright lie, used as legitimate means to achieve political ends, have been with us since the beginning of recorded history. Truthfulness has never been counted among the political virtues, and lies have always been regarded as justifiable tools.’ (Hannah Arendt, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1971/11/18/lying-in-politics-reflections-on-the-pentagon-pape/)

VI. The role and status of the public intellectual are to be understood in terms of the changing nature and scope of public media, discourse and knowledge as it has been shaped by profound changes in public media landscapes. Part of the reason for philo-journalism.

- Every intellectual operates on a materiality. This takes the form not only of institutions but also technologies that make it possible to transmit ideas and generate audiences. In classical times, this materiality involved the printing press and books, but, today, also includes a series of digital tools through which linguistic and geographic barriers can be surmounted at a speed that was unthinkable only a few decades ago. (Mauro Basaure, Alfredo Joignant & Rachel Théodore, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-022-09417-y)

- Independent journalism – the kind that favours public interest over political, commercial, or factional agendas – is in peril. The rapid erosion of the business models underpinning media sustainability has deepened a crisis in the freedom and safety of journalists around the world. The global response to these challenges in the coming decade will be decisive for the survival of a democratic public sphere. (UNESCO, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380618)

- Key findings:

- Media freedom has been deteriorating around the world over the past decade;

- In some of the most influential democracies in the world, populist leaders have overseen concerted attempts to throttle the independence of the media sector;

- While the threats to global media freedom are real and concerning in their own right, their impact on the state of democracy is what makes them truly dangerous;

- Experience has shown, however, that press freedom can rebound from even lengthy stints of repression when given the opportunity;

- The basic desire for democratic liberties, including access to honest and fact-based journalism, can never be extinguished. (Sarah Repucci, Freedom House, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-and-media/2019/media-freedom-downward-spiral)

- What is journalism? What is it for? What roles does it play in political life, and what roles should it play? Which of these roles are specific to democracy? Which of them, if any, are specific to American democracy? What should count as news? How should it be determined what’s important for the public in a given place to know about? What are been the benefits and pitfalls of professionalised journalism? What challenges and opportunities face journalists and journalism in the age of social media? (Susanna Siegel, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d02a7d58353560001b37a3b/t/6130ee81293e0862282b9554/1630596739866/Phil+J_F21_Syllabus_Final.pdf)

- Philo-journalism starts with the question, what does it mean to communicate the truth? Is it still possible in a post-truth world, and why does it matter?

- Journalism demands writing, analysis and research skills, as well as interviewing. It requires changes in the ecology of public media platforms, including online and broadcast. It needs a philosophy of public communication that understands changes in global media and the way these changes change the way we think, act and see the world around us.

- American journalist Helen Thomas once argued that the role of journalism in a democracy is truth-seeking. In a public sphere continuously populated by propaganda, fake news, and organised lying, this role may seem more important than ever. But which truths should journalism orient itself around making salient? What principles should guide the selection of news stories? What roles can journalism play in democracy, and what roles should it play, more generally, in social and political life? (Eraldo Souza dos Santos and Susanna Siegel, https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/mancept/mancept-workshops/programme-2022-panels/philosophy-and-politics-of-journalism/)

- Philo-journalism needs to investigate the media infrastructures of truth-making and communication, the power of platforms-based social media to propagate and spread misinformation, lies and fake news and to craft false political narratives to govern through conspiracy. Democracy rests on meta-epistemic principles of a fifth-generation set of media that needs to be able to ascertain truth as its basis.