Could you explain critical pedagogy, a philosophy of education and social movement?

Critical pedagogy has become a broad umbrella term that unites a disparate compendium of ideas from critical social theory generated since the 1970s. Numerous tributaries of educational theory and practice have grown out of the vast reservoir of critical educational thought, and these tributaries have appeared in tandem with social and political upheavals around the world. Essentially, critical pedagogy is a problem-posing approach to being in and transforming the world.

The dust never settles on critical pedagogy – it’s a fluid social movement and philosophy. Pedagogically, it is a way of teaching against the grain, making the pedagogical more political and the political more pedagogical. As the American educator, scholar, and cultural critic Henry Giroux would say, it means moving outside and alongside conventional boundaries concerning class, race, gender, and sexuality; creating the contexts for learners to independently think critically and use their lived experiences to establish lifelong projects of serving others; and helping students and their communities transform while holding established power relations accountable.

Paulo Freire was a founding figure of critical pedagogy whom you got to know quite well. Could you tell us more about his philosophy?

Critical pedagogy acknowledges that our objective and subjective worlds are internally related. This understanding is central to comprehending what Brazilian philosopher and educator Paulo Freire meant by his term conscientização, the development of critical consciousness for the liberation of humanity. This eventually stipulates the development of a transformative praxis, the interpenetration of theory and practice, the knife edge upon which we balance our precarious lives which requires that humans, both individually and collectively, act as subjects in the world as opposed to being objects to be acted upon.

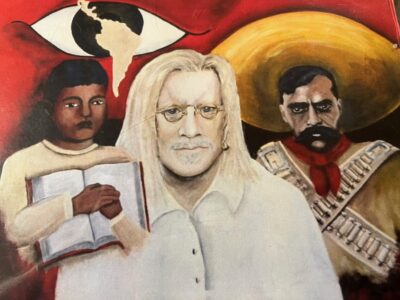

Painting by Laura Herrera

As an approach that is built upon theory and practice, or action and reflection, critical pedagogy is a dialectical philosophy that is very different from the rational, formal logic of, say, the positivistic sciences. In dialectics, things can only be understood in relation to each other and cannot be analysed as independently existing pieces. Freire teaches that human consciousness is distinct because humans have ‘the capacity to adapt […] to reality plus the critical capacity to make choices and transform that reality’. Only when we understand the dialectical relationship between consciousness and the world – that there is no separation between these – can we begin to ‘read the word and the world’ simultaneously and transform the world. We understand that our consciousness comes from dialectical interaction with that world and other humans, so we need to consider our consciousness, first and foremost, as a social consciousness. We don’t think independently from others. All of our ideas are populated by other people’s meanings. Praxis occurs when we exercise our volition along with our critical consciousness to move beyond our conditioning process and social determinations to change our world.

Another concept of Freire’s is dialogue. Throughout history, dialogue has helped us to communicate with each other much more critically, created solidarity among human beings and helps us collectively interact with the world. It prevents us from simply depositing our ideas into other people’s minds – a process that Freire condemned as ‘banking education’. In dialogue, we can’t treat others as objects. In dialogical learning, we are made and remade as learners and teachers.

How has critical pedagogy evolved?

There have been a lot of books written about critical pedagogy, and it’s become a flourishing publishing industry. But the practical impact of critical pedagogy is hard to discern. There are no doctoral programmes to my knowledge in critical pedagogy, but there are plenty of social justice initiatives clearly influenced by it. There is now a range of political dimensions to critical pedagogy, including liberal, progressive educators identifying as critical pedagogues who are surprisingly critical of Marxist educators within the field of critical pedagogy, such as myself, who advocate openly for education to be put into the service of building a socialist alternative to capitalism.

One of the major evolutionary directions in which critical pedagogy is currently moving is digitalised learning. As machine learning, robotics, and virtual reality dominate our digital lifeworlds through expansion and market capitalisation, critical pedagogy conceptualises information as a form of social power. It’s committed to resisting its weaponisation, especially at a time of massive population surveillance through digital technologies. I’ve published a book on this with a young Croatian professor, Petar Jandrić, but I do not consider myself an expert in this area. It is the younger scholars who are moving critical pedagogy into new and important domains, such as digital learning, as well as inter-, trans- and anti-disciplinary approaches to the intersections between critical pedagogy and information and communication technologies.

What do you think are the main criticisms of critical pedagogy and how do you counter these?

One of the major criticisms by students has been critical pedagogy’s perceived focus on theory, which learners sometimes regard as too dense and elitist. They are less likely to be readers of books than in my student days. Many students regard teaching as entertainment today – they don’t want to get depressed learning about how difficult, painful, and exploitative the world can be.

Other students are trapped in the post-truth, fact-free universe of today’s social media where there exists no right or wrong, just temporarily held opinions about issues. There is a lack of understanding of what constitutes an argument, how to adjudicate the argument, and what constitutes an opinion. Students can retreat to digital platforms where they do not have their ideas questioned or challenged. Teachers, too, can fall victim to these same attitudes. Many of them focus on content without giving much thought to how students will respond. Students have sometimes responded in my class with the assertion: That’s your opinion professor, I have my own!

Students need opportunities to acquire new and challenging experiences focusing on the socio-historical and political forces and contexts which reflect their own social identities. That is difficult to accomplish in today’s classroom settings. Too many students receive knowledge passively in a decontextualised form, for the students to memorise and repeat on standardised tests. Critical pedagogy, however, encourages students to grasp knowledge dialectically in relation to current problems and injustices to transform society in the interest of social justice, within an ethics of compassion, caring, and fairness. What is needed is a problem-posing model of education which can lead to critical consciousness resulting from a dialogical engagement about the manifold complexities of students’ lives and lived experiences.

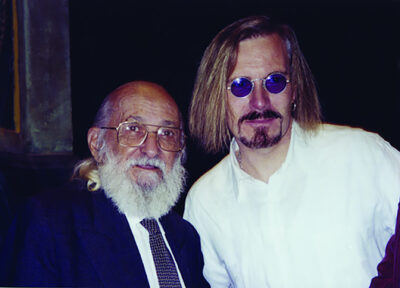

Paulo Freire with Peter McLaren, Nebraska, 1996.

Do you think that critical pedagogy offers solutions to inequalities and oppression?

Critical pedagogy isn’t designed to offer solutions to oppression, to inequalities in our social universe. It’s problem-posing. But that doesn’t mean we can’t or don’t try to offer solutions. Critical pedagogy is designed to create the conditions for educating creative thinkers who can, individually and collectively, contribute to the betterment of society and help the most immiserated and vulnerable, as a result of having developed a dynamic, ‘protagonistic’ agency and awareness. Strategies, skills, and problem-solving approaches foster the creation of critical, revolutionary intellectuals, who understand that the social, political, and economic realities of life can be challenged and changed. Students develop a ‘political criticality’ spawned in the lifeworld of dialogical engagement that leads to transformative praxis. In critical pedagogy, students and teachers together control the educational process to engage in a larger sociopolitical struggle, challenge oppressive social conditions, and work towards a more just society.

The distinguishing elements I have brought to North American critical pedagogy are, firstly, Marxist class analysis, and, secondly, liberation theology, especially in the context of Catholic social justice education. During my time in Latin America, I was educated about the nuns and priests, conversant in scripture and Karl Marx, who worked to liberate their communities from oppression. Students were interested in exploring various spiritual traditions, so I began classes in spirituality and critical pedagogy, incorporating insights by the great theologians Jose Porfirio Miranda and James Cone. They see their faith as aligned with what critical pedagogy is attempting to accomplish.

Critical pedagogy, then, can sensitise students to the suffering of marginalised groups in society and create the conditions for dialogue and debate around issues such as systemic racism, the struggle of the LGBTQ community around the world, economic inequality, racism, the surveillance state, global capitalism, attacks on democracy and its global implications, disability rights, civil rights, and women’s rights.

Who will be the future leaders of critical pedagogy?

The future leaders of critical pedagogy will be a mixture of people: Indigenous organisations standing up for their communities and fighting for a more sustainable future for the planet; Black Lives Matter activists; school teachers defending the right to teach critically; cultural workers protecting the rights of political refugees from Syria and Yemen; and volunteers from Ukraine helping the victims buried in the rubble of conflict. All will revisit the work accomplished by critical educators and provide new insights from their own standpoints. Some will be university graduates, some will not. I assume most will be teachers and researchers, but many will be grassroots activists or working behind the scenes in relative anonymity.

Critical pedagogy can be activated in many different sites and contexts. We are all learners, and we teach others – teaching doesn’t just have to happen in a classroom. We all have insights that make a practical impact on our own and others’ lives. From the standpoint of critical pedagogy, teachers are not restricted to those in formal educational institutions. They are courageous individuals whom Freire describes as ‘cultural workers’, ‘those who dare to teach’ in whatever context they find themselves.

Originally published at Research Outreach (November 17, 2022): https://researchoutreach.org/articles/pushing-boundaries-peter-mclaren-importance-critical-pedagogy-inside-outside-classroom/