Introduction

In a story by Minna Salami (2015) in The Guardian entitled ‘Philosophy Has to be about More than White Men,’ the following claim is made, ‘The campaign to counter the narrow-mindedness of university courses is gathering pace because philosophy should investigate all human existence.’ Salami refers to a 20-minute video with the title Why is My Curriculum White? made by UCL (University College London) students who propose responses to this question pointing out the lack of awareness that the curriculum is white and comprised of ‘white ideas’ by ‘white authors’ and is a result of colonialism that has normalised whiteness and made blackness invisible. This is a fundamental educational challenge that has not been addressed by the educational establishment nor by most philosophers, including philosophers of education, most of whom are white men and women. Racism rarely figures on philosophy of education conference agendas and papers discussing the ethics of education that tend to talk in general and abstract terms neglecting issues of race or gender. Salami wrote a blog rather than a philosophy paper making the argument that ‘we should not dismiss white, western, or male thinking simply on the premises that it is white, western or male,’ while at the same time acknowledging, by reference to Michael McEachrane’s statement, ‘Modern philosophical concepts of personhood, human rights, justice and modernity are deeply shaped by race.’

My purpose is to take seriously the issues that she and UCL students are raising. In view of the events in Ferguson, USA, where social unrest and a series of ongoing protests began the day after the shooting of Michael Brown (August 9, 2014), it is necessary to raise the question again of the roots of US racism and racism in general. This is exactly the topic of The Stone interviews conducted by George Yancy of prominent American philosophers, for example, ‘Noam Chomsky on the Roots of American Racism.’ Chomsky provides a brief history in terms of slave labour camps, a major factor in America’s success and current wealth, the harsh criminalisation that followed the end of slavery and the new Jim Crow that neoliberalism under Reagan initiated in the 1970s as part of the ‘drug war.’ Chomsky says,

The national poet, Walt Whitman, captured the general understanding when he wrote that ‘The nigger, like the Injun, will be eliminated; it is the law of the races, history…. A superior grade of rats come, and then all the minor rats are cleared out.’ It wasn’t until the 1960s that the scale of the atrocities and their character began to enter even scholarship, and, to some extent, popular consciousness, though there is a long way to go.

Yet Ferguson demonstrates that Obama’s ‘post-racial America’ is a kind of mythology that persists despite the critical scholarship of Yancy and Chomsky and many others, including Black women scholars. Part of the problem is what scholars call ‘internal colonisation,’ a psychological state that Césaire, Fanon, and Malcolm X knew too well meant that the dominant ideology had become internalised and thus part of the psychological make-up of the oppressed. This notion of ‘internal colonisation’ was first recognised by the movement called Négritude.

The Concept of Négritude

Négritude was a literary movement by French-speaking African and Caribbean writers that philosophically established the fact and value of Black selfhood and identity during the 1930-50s as a counternarrative to French colonial rule. Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism (1955) and his Cahier d’un Retour au Pays Natal, composed in 1939 and translated as Return to My Native Land (1969), is a lyric and sustained narrative long poem (over 1055 lines in the original French) that became the anthem for the Négritude movement and helped lay the foundations for the emergence of postcolonial studies in the 1970s. Reminiscent of W.E.B. DuBois’ (1903) The Souls of Black Folk in that it explores the notion of black selfhood, Césaire explores identity through the metaphor of trying on masks and utilises uncompromising language that emulates a virulent self-hatred. Fanon’s (1952) Black Skin, White Mask also used the device of the mask to explore the psychology of racism under colonialism, focusing on the divided self-perception of the Black subject who had lost his (sic) culture. In the 1986 Pluto Press edition of the English translation by Charles Lam Markmann, Homi Bhabha notes, in his Foreword ‘Remembering Fanon: Self, Psyche and the Colonial Condition,’ how Fanon’s ideas are effectively ‘out of print’ in Britain with little acknowledgement except through mythical means as the avenging angel of Black revolutionary activity.

Léopold Sédar Senghor, one of the founders of the movement and an African political leader, was a poet and intellectual who, with Aime Césaire and Leon Damas, built the Négritude movement. Senghor, in the late 1920s, went to France to prepare himself to enter the École Normale Supérieure. In the 1930s, he became one of the main voices for the concept of Négritude and, after WWII, entered politics in Senegal, breaking from French socialism to build his own party that rested on Muslim support. He became the first president of an independent Senegal in 1960 and held the post until 1980. He published his first collection of poetry in 1945 and continued to write and publish poetry throughout his life and presidency. His poetry focused on the Black experience of the natural and social worlds in a lyrical and sensual form that he thought characterised Black sensibilities. His Liberté 1: Négritude et Humanisme (1964), part of a five-volume collection, contains some of his early speeches and provides background to the emergence of Black African culture. His On African Socialism (1964) takes issue with classical Marxism to emphasise Marxism as a humanism and the Marx of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. As Barbara Celarent comments:

He wants his hearers not to reject the Negro-African heritage for a Europeanised materialism, for Marx’s ‘terribly inhuman metaphysics, an atheistic metaphysics in which mind is sacrificed to matter, freedom to the determined, man to things.’

Senghor tended to avoid Marxism and anti-Western ideology that was characteristic of this time in Africa. The African Studies Centre at Leiden, which provides an introduction to his work and a list of his publications, writes of Senghor:

As co-founder of the Négritude movement, Senghor tried to awaken African consciousness and dispel feelings of inferiority. The term ‘Négritude’ embraces the revolt against colonial values, glorification of the African past, and nostalgia for the beauty and harmony of traditional African society. The concept is defined in contradistinction to Europe. According to Senghor, the African is intuitive, whereas the European is more Cartesian. This statement led to numerous protests, with Sartre even declaring that Négritude was ‘an antiracist racism.’ Senghor’s poetry often displayed what he called ‘this double feeling of love and hate’ regarding the ‘white’ world. Though his African nationalism emerged in his poetry and his politics, he refused to reject European culture.

Little known, Anténor Firmin, a Haitian anthropologist, wrote a book called De l’Égalité des races humaines (On the Equality of the Human Races), published in 1885 in response to Arthur de Gobineau’s work Essai sur l’Inégalité des Races Humaines (Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races), which proclaimed the superiority of the white race arguing in one of the earliest examples of scientific racism that civilisations based on ‘mixed races’ will fail. Firmin, together with Henry Sylvester Williams, a Trinidadian lawyer, and Bénito Sylvain, organised the first Panafrican conference in London in 1900, a conference attended by WEB D Bois, who was made responsible for writing the general report. Some five similar conferences were held during the twentieth century that eventually led to the African Union.

As is also well known, the Harlem Renaissance, originally named ‘The New Negro Movement,’ constituted the rebirth of African-American arts that began in the 1920s lasting through the 1930s, strongly influenced the Négritude philosophy with the flowering of music, fashion, dance, poetry, drama, art and literature. The Harlem Renaissance was partly the result of the Great Migration out of the South to the new Black neighbourhoods in the North in places like Manhattan. There were race riots in 1919 as tensions grew over economic competition for jobs. New dramas such as Three Plays for a Negro Theatre rejected the stereotypes of the black and white minstrel show tradition. New Black newspapers and academic journals were launched. Religion played a strong role, with the ideology of inclusion, and Islam and Black Judaism came to Harlem to promote social and racial integration as well as a Panafricanism. All Black productions of theatre and opera, for example, Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, saw art, theatre and music as a means of artistic self-expression but also a way of expressing dimensions of human equality.

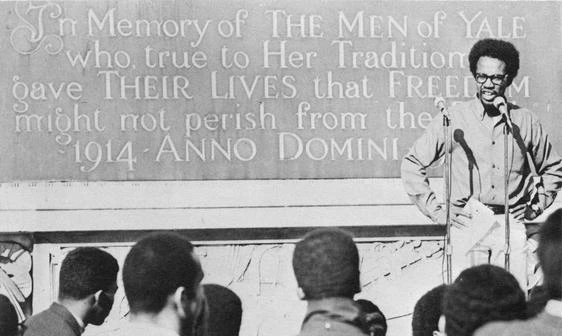

The Emergence of Black Studies

The groundwork for Black Studies was established and laid down at the turn of the century with works by Du Bois like The Philadelphia Negro (1898). It took Du Bois until 1941 to present a program for Black Studies to the Annual Conference of the Presidents of Negro Land-Grant Colleges, and the first programme did not appear until twenty-five years later. (See the W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute at Harvard, established in 1975). Afro-American studies departments emerged in the 1960s after student activism, although the reconstruction of African-American history began in the late nineteenth century. The origins cannot be separated from the Civil Rights context. Students for a Democratic Society at Berkeley held a conference in 1966 called ‘Black Power and its Challenges,’ inviting Black civil rights leaders. Then came the demand for Black Studies:

The black freedom movement, in both the civil rights phase (1955–1965) and Black Power component (1966–1975), fostered the racial desegregation and the empowerment of black people within previously all-white institutions. The racial composition of US colleges changed dramatically. In 1950, approximately 75,000 blacks were enrolled in colleges and universities. In the 1960s, three-quarters of all black students attended HBCUs [Historical Black Colleges and Universities]. By 1970, approximately 700,000 blacks were enrolled in college, three-quarters of whom were in predominantly white institutions.

Black Studies was also strengthened through the growth of Black Legal Studies and Critical Legal Studies in the 1970s, which drew heavily from changes to the political culture occurring during the counterculture of the 1960s. Critical Legal Studies explored how the practices of legal institutions, legal doctrine, and legal education worked to buttress dominant white culture and the rule of law devoid of hidden class and race interests. Critical race studies applied critical theory to the intersections of race, law, and power, providing a critique of liberalism and revisionist accounts of American civil rights law. Critical race theory and critical pedagogy also pursued these issues theorising the notion of whiteness as property. As Delgado and Stefancic comment:

Although CRT began as a movement in the law, it has rapidly spread beyond that discipline. Today, many in the field of education consider themselves critical race theorists who use CRT’s ideas to understand issues of school discipline and hierarchy, tracking, controversies over curriculum and history, and IQ and achievement testing.

Even with these movements for justice and social change, recent surveys would suggest that little progress has been made in eliminating systematic or institutional racism in the US.

The Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights movement was a movement to end segregation and racial discrimination in the USA during the initial period from 1954 to 1968 that focussed on nonviolent protest and campaigns of civil disobedience. This was an age of protest with mass mobilisation, which replaced litigation and was perhaps ignited by the famous case of Brown vs The Board of Education in 1954, which was the beginning of the end of segregation of schools. This case was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court, which overturned the Plessy vs Fergusson case of 1896 that mandated state segregation and held that, as long as there were separate facilities for races, segregation did not violate the 14th Amendment that included equal protection under the law provision. The Supreme Court decision came at a time strongly influenced by the new international agencies’ emphasis on equality and the UNESCO document The Race Question (1950), which was an attempt to clarify the false claims of scientific racism, especially in view of the experience of Nazi racism. Claude Levi-Strauss and Ashley Montagu, alongside a group of authors, expressed a concern for human dignity and the equality of all citizens before the law declaring that Homo sapiens was one species, that ‘race’ was a classificatory concept that provided no support for ‘pure races’ or reproduction between persons of different races. The Brown vs The Board of Education Supreme Court decision found no place for ‘separate but equal’:

Segregation of white and coloured children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the coloured children. The effect is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system. […]

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Civil Rights movement, about which much has been written, was a nonviolent movement to gain legal equality before the law, to uphold the 15th Amendment of the Constitution, and to secure constitutional rights of African Americans, thus ending the era of state-mandated segregation, especially focusing on equality of opportunity and equality of access to public institutions including education and the right to vote. It is impossible to capture all the elements, personalities and events of the civil rights movement in an essay of this kind; the historical sources include much contemporary Black history and primary sources collections, including streaming videos and oral histories. From a broad philosophical viewpoint, the aim of the movement was to achieve equal citizenship:

In contemporary political thought, the term ‘civil rights’ is indissolubly linked to the struggle for equality of American blacks during the 1950s and 60s. The aim of that struggle was to secure the status of equal citizenship in a liberal democratic state. Civil rights are the basic legal rights a person must possess in order to have such a status. They are the rights that constitute free and equal citizenship and include personal, political, and economic rights. No contemporary thinker of significance holds that such rights can be legitimately denied to a person on the basis of race, colour, sex, religion, national origin or disability. Antidiscrimination principles are thus a common ground in contemporary political discussion. However, there is much disagreement in the scholarly literature over the basis and scope of these principles and the ways in which they ought to be implemented in law and policy.

Critical Race Theory and Black Legal Studies

It is a sobering thought that Critical Race Theory, which emerged from the discipline of law only in the 1970s, was developed by a range of critical theorists because they thought that the civil rights movements of the 1960s had effectively stalled. As Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, in their introduction to Critical Race Theory, write:

Critical race theory sprang up in the mid-1970s, as a number of lawyers, activists, and legal scholars across the country realised, more or less simultaneously, that the heady advances of the civil rights era of the 1960s had stalled and, in many respects, were being rolled back. Realising that new theories and strategies were needed to combat the subtler forms of racism that were gaining ground, early writers such as Derrick Bell, Alan Freeman, and Richard Delgado … put their minds to the task. They were soon joined by others, and the group held its first conference at a convent outside Madison, Wisconsin, in the summer of 1989.

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, the Black feminist critical race legal scholar, looking back on twenty years of critical race theory, begins: ‘Today, CRT can claim a presence in education, psychology, cultural studies, political science, and even philosophy. The way that CRT is received and mobilised in other disciplines varies, but it is clear that CRT has occupied a space in the canon of recognised intellectual movements that few other race-oriented formations have achieved.’ She mentions the texts by Du Bois, Joyce Ladner (The Death of White Sociology), Robert Guthrie (Even the Rat Was White), Tukufu Zuberi and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Toni Morrison (Playing in the Dark) that contested the academy had ‘disciplined knowledge about race’ and goes on to explore what ignited CRT in law.

It is indeed salutary to understand how CRT emerged as an intellectual movement, and Crenshaw is at pains to point out that CRT was not simply ‘a philosophical critique of the dominant frames on racial power. It was also a product of activists’ engagement with the material manifestations of liberal reform.’ She also remarks how ‘liberal visions of race reform and radical critiques of class hierarchy failed in different ways to address the institutional, structural and ideological reproduction of racial hierarchy.’ Crenshaw provides a clear picture of the movement’s origins and political formation beginning with the 1989 conference and the way in which CRT became ‘interdisciplinary, intersectional, and cross-institutional.’ What is important about Crenshaw’s paper is the questioning of Obama’s post-racial ideology and the, then, ‘configuration of racial power’ and ‘the entrapment of civil rights discourse more broadly.’

It reminds us how quickly the framework of racial power changes and how, even under the first African-American administration, viewed by some as fulfilling the dream of Martin Luther King Jr., the ideological dimensions of ‘post-racial’ policies increasingly became exposed during Obama’s two terms, especially after the Great Recession where Blacks and other minorities lost heavily in the housing and job crises. Black Lives Matter, the social movement for racial justice formed during Obama’s administration, goes beyond the ‘extrajudicial killings of Black people by police and vigilantes’ to ‘(re)build the Black liberation movement.’ The movement began in 2013 when George Zimmerman was acquitted of shooting a Black teen, Trayvon Martin. The movement organised street demonstrations following the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in New York City. One of the editors of this volume comments that these were started and organised by queer black women, who have been written out of herstory. Race relations in the post-election climate of Donald Trump’s administration seemed destined to deteriorate as Trump intensifies racial divisions and politically exploits racism, appointing top advisors who have been criticised for their association with, and condonement of, white supremacist groups.

Antiracist Education

Antiracist education differed strongly from multicultural education, designed to eliminate the practice of classifying people according to their skin colour or racial identity. Antiracist education in Britain and the US criticised the liberal assumptions of multiculturalism by uncovering and dismantling the hidden power structures that were responsible for inequality and racism in institutions. Educational institutions, in particular, it is claimed, play a fundamental role in reproducing white privilege, and schools are seen as places where racism and stereotypes against ethnic and minority groups take place through a variety of means. The curriculum and pedagogy have been analysed as sites for this kind of reproduction that takes place through misinterpretations of history and the ‘othering’ of minorities, shaping both white and non-white subjectivities and identities. Gillborn, focusing on the UK, argues that ‘conventional forms of anti-racism have proven unable to keep pace with the development of increasingly racist and exclusionary education policies that operate beneath a veneer of professed tolerance and diversity,’ especially in the context of ‘conservative modernisation’ and the resurgence of racist nationalism which if anything has increased under austerity programs since Gillborn wrote his essay. He concludes by suggesting that ‘Racism is complex, contradictory, and fast-changing: it follows that anti-racism must be equally dynamic.’

Gillborn’s analysis is entirely salutary. After 50 years of struggle in the form of multiple movements, it is heartbreaking and extremely frustrating for Blacks, for indigenous peoples, for minority groups and for society as a whole that there has been so little progress or that social change has been resisted, destabilised, and under- mined. At the same time, it is encouraging that a new generation of students and scholars is actively pursuing ‘whiteness as ideology’ as with the UCL Collective.

Why Is the Curriculum White?

The UCL collective remarks:

Although often treated as something biological, fixed or even benevolent, ‘race’ is an ideologically constructed social phenomenon. Therefore, when we talk about whiteness, we are not talking about white people, but about an ideology that empowers people racialised as white.

To the question ‘why is the curriculum white?,’ they provide eight answers (summarised here):

- To many, whiteness is invisible.

- A curriculum racialised as white was fundamental to the development of capitalism.

- Because its power is intersectional.

- The white curriculum thinks for us; so we don’t have to.

- The physical environment of the academy is built on white domination.

- The white curriculum need not only include white people.

- The white curriculum is based on a (very) popular myth.

- Because if it isn’t white, it isn’t right (apparently).

Even if one disagrees with the statement of these reasons, it is clear that there is a general philosophical problem concerning the curriculum and that efforts to resolve it so far have been only partially effective. One of the difficulties has been that western philosophy itself has been part of the problem rather than part of the solution. Of all disciplines, it has seemed most resistant to taking race seriously and only recently have Black philosophers begun to deconstruct and dismantle the ideology of ‘whiteness’ as it affects our institutions in education, in government, in the academy and in the law.

A combination of philosophical critique and activism is required. Rhodes Must Fall is another example of an antiracist protest movement. It began in 2015 at Cape Town University, campaigning for the removal of the statue of Cecil Rhodes, which was regarded as an inappropriate symbol of a colonial era based on the exercise of racial colonial power. Rhodes is seen as a racist, a symbol of colonialism and someone who prepared South Africa for the introduction of the apartheid system. While the movement began as a protest by students and staff against institutional racism at the University of Cape Town, it developed into a wider student movement designed to decolonise higher education across South Africa and also at Oxford University, where Rhodes was a benefactor. Rhodes Must Fall in Oxford states its aims as follows:

Rhodes Must Fall in Oxford (RMFO) is a movement determined to decolonise the institutional structures and physical space in Oxford and beyond. We seek to challenge the structures of knowledge production that continue to mould a colonial mindset that dominates our present.

Our movement addresses Oxford’s colonial legacy on three levels:

1) Tackling the plague of colonial iconography (in the form of statues, plaques and paintings) that seeks to whitewash and distort history.

2) Reforming the Euro-centric curriculum to remedy the highly selective narrative of traditional academia – which frames the West as sole producers of universal knowledge – by integrating subjugated and local epistemologies. This will create a more intellectually rigorous, complete academy.

3) Addressing the underrepresentation and lack of welfare provision for Black and minority ethnic (BME) amongst Oxford’s academic staff and students. (Emphases given).

The ‘structures of knowledge production’ includes the disciplines and the curriculum, the physical space of the university campus, and its symbolic colonial representations. We might also add to this characterisation by mentioning the political economy of a publishing world dominated by Anglo-American interests and English as the global academic language, even for China and other Asian countries. This is to recognise the strategic nature of academic journals, the uneven distribution of academic journal nature, and the emergence of big data distribution and bibliometric systems that determine international rankings. Of all the disciplines, philosophy, perhaps, is the oldest and one of the most influential in promoting colour-blindness and ‘whiteness’ at the expense and recognition of Black consciousness, identity, responsibility and action.

White Philosophy

I have used the term ‘white philosophy’ to designate the notion of colour-blind philosophy, which in my view,

has special application to American philosophy for its extraordinary capacity to ignore questions of race and for its incapacity to recognise the centrality of the empirical fact of blackness and whiteness in American society and as part of the American deep unconscious structuring politics, economics and education.

I have traced the development of American pragmatism, especially in the work of Stanley Cavell and Richard Rorty (and also John Dewey), to show how race is all but peripheral in the development of the American philosophical canon. I also charted the beginning of Cornel West’s challenge to white philosophy crystallising in the late 1980s, beginning with his book The Evasion of American Philosophy. Paradoxically, as I remark in the paper, ‘West himself names Wittgenstein, Heidegger and Dewey as those philosophers who set us free from the confines of a spurious universalism based on a European projection of its own self-image’ (p. 153).

The recognition of the whiteness of philosophy and its effects is a complex matter. In education, it is important to recognise, with critical pedagogy scholars like Henry Giroux, Michael Apple, and Peter McLaren, sociologists like Gillborn, Barry Troyna and Fazal Rizvi, and feminist scholars of colour such as Aileen Moreton-Robinson, Gloria Ladson-Billings and Heidi Safia Mirza, to name only a few, that the curriculum is an official selection that structures knowledge in ways that privilege a particular construction of knowledge and the history of knowledge. It is no longer surprising to us after establishing new awareness sensitivities to past knowledge that some of the most eminent philosophers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – Nietzsche, Heidegger, Wittgenstein – were strongly racist, at least at some points in their lives. American philosophers, on the whole, have been largely agnostic on the question of racism. Only in the 1990s does the question come up for study and review.

The lack of recognition of cultural context, of contextualism in general, in curriculum theory, was perpetrated in philosophy of education by Paul Hirst and R.S. Peters’ forms of knowledge thesis that focused on propositional knowledge and admitted no historical understanding of evolving forms of knowledge let alone their cultural embeddedness and variation. Park gives an account of the development of philosophy as an academic discipline in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. During this period, European philosophy influenced by Kant formulated the history of philosophy as a March of progress from the Greeks to Kant. It was an account that demolished existing accounts beginning in Egypt or Western Asia, thus establishing an exclusionary canon of philosophy. Hegel’s account of world history was strongly racist and imbued European philosophy with a prejudicial history we are still trying to escape from. These two philosophers contributed so much to a contemporary understanding of modernity as fundamentally Western.

Roy Martinez, as the basis for his collection On Race and Racism in America, asks: ‘Given the racial complexity of the United States – not to mention the racism of its foundations and its persistence – why is it that the most influential white philosophers have not addressed the issue of race, its social construction and myth, and the problems it raises on a daily basis?’ More recently, Ason Stanley and Vesla Weaver, in the New York Times Stone forum, ask, ‘Is the United States a “Racial Democracy”?’ where racial democracy is defined as ‘one that unfairly applies the laws governing the removal of liberty primarily to citizens of one race, thereby singling out its members as especially unworthy of liberty, the coin of human dignity.’ Referring to the increase of statistics for Black imprisonment since the 1970s – an astonishing 517% increase from 1966 to 1997 – Stanley and Weaver conclude that the system that has emerged in the last few decades in the US is a racial democracy.

Sean Harvey and other historians have mapped closely the influence of ‘race’ in early America and the way a basically contestable philosophical idea provided foundations for American institutions:

‘Race,’ as a concept denoting a fundamental division of humanity and usually encompassing cultural as well as physical traits, was crucial in early America. It provided the foundation for the colonisation of Native land, the enslavement of American Indians and Africans, and a common identity among socially unequal and ethnically diverse Europeans. Longstanding ideas and prejudices merged with aims to control land and labour, a dynamic reinforced by ongoing observation and theorisation of non-European peoples. Although before colonisation, neither American Indians, nor Africans, nor Europeans considered themselves unified ‘races,’ Europeans endowed racial distinctions with legal force and philosophical and scientific legitimacy, while Natives appropriated categories of ‘red’ and ‘Indian,’ and slaves and freed people embraced those of ‘African’ and ‘coloured,’ to imagine more expansive identities and mobilise more successful resistance to Euro-American societies.

A critical question for me as a white male philosopher is whether the Western tradition in philosophy has the intellectual resources within to transform itself and come to terms with the historical effects and traces of racism that are invested in our institutions and in our knowledge traditions. I think it has – as a teacher, I have to believe this – but we are only at the very beginning of this process of transformation, and the UCL collective and Rhodes Must Fall have initiated student-led movements that have the potential to provoke and demand curriculum change.

Acknowledgement: This essay is based on a chapter entitled ‘Why Is My Curriculum White?’ in Dismantling Race in Higher Education (Palgrave McMillan, 2018), edited by Jason Arday and Heidi Mirza.